The ability to see visible waves of light can be beneficial for determining the size, shape, distance, and speed of things in our surrounding environments. But in many situations, reliance on sight might not be the best option for the remote detection of objects. For example, most animals do not have eyes on the backs of their heads; many cannot see very well at night; and some live in the depths of the ocean where visible light doesn’t reach. Yet these conditions don’t hinder the ability to sense objects for many animals. So, how do humans and other animals “see” distant objects without depending on the use of sight?

One answer is that other types of waves outside of visible light exist and animals have developed methods for detecting them. Two of these methods, sonar and radar, are man-made detection systems that allow us to “see” what our eyes can’t. The other, echolocation, is a natural way for some animals to detect motion through sound waves.

Radar

Radar is a system used to detect, locate, track, and recognize objects from a considerable distance. R.A.D.A.R is an acronym for “radio detection and ranging.” It was initially developed in the 1930s and 1940s for military use, but is now common for civilian purposes as well. Some of these uses include weather observation, air traffic control, and surveillance of other planets.

Radar works by sending out radio waves, a type of electromagnetic wave, in pulses through a radio transmitter. The waves are reflected off of objects in their path back toward a receiver that can detect those reflections. Radar devices usually use the same antenna for transmitting and receiving, which means the device switches between being active and passive. The received radio wave information can help observers determine the distance and location of the object, how fast it is moving in relation to the receiver, the direction of travel, and sometimes the shape and size of the objects, too.

Radio waves have the longest wavelengths and lowest frequencies of all electromagnetic waves. Because they move slower and require less energy, they travel well through adverse weather conditions like fog, rain, snow, etc. Detection systems like lidar that operate through infrared and visible waves with shorter wavelengths and higher frequencies do not function well in such conditions.

While radar can effectively move through or around various environmental conditions, it is much less effective underwater. The electromagnetic waves of radar are absorbed in large bodies of water within feet of transmission. Instead, we use Sonar in underwater applications.

Sonar

S.O.N.A.R, an acronym for “sound navigation and ranging,” is a similar system to radar in terms of transmitting and receiving waves through pulses to determine distance and speed. However, it functions through the use of sound waves and is highly effective underwater.

Sound waves are mechanical waves, which means they are oscillations, or back and forth movements at regular speeds, of matter. When a mechanical wave strikes an obstacle or comes to the end of the medium it travels in, some portion of the wave is reflected back into the original medium. Water turns out to be a fantastic medium – albeit a slow one – for carrying mechanical waves long distances, making Sonar the top choice for underwater object detection.

Echolocation

Echolocation is a natural sound wave transmission and detection method used by animals to accomplish the same goal of object detection. Though sometimes referred to as sonar in casual conversation, echolocation requires no human-made device to function and is used both above and below water. Animals use echolocation by sending out sound waves in the air or water before them. They can then determine information about objects in their path through the echoes produced when those sounds are reflected.

Echolocation can be utilized by any animal with sound-producing and sensing capabilities. Humans have been known to develop methods of systematically tapping canes or clicking their tongues to produce the sounds needed for echolocation. However, echolocation is more generally associated with the use of ultrasound by non-human animals. Ultrasound is sound that has a mechanical wave frequency higher than the human ear can detect though they operate the same as audible sound waves.

Bats are among the most well-known users of echolocation. They use relatively high, mostly ultrasonic wavelengths and some can create echolocating sounds up to 140 decibels – higher than a military jet taking off only 100 feet away. In order to handle such intense sound wave vibrations, bats turn off their middle ears by just before calling to avoid being deafened by their own calls. They use muscles in their middle ear to pull apart bones that carry sound waves to the inner ear leaving no path for the sound waves to damage the cochlea. Similar to radar devices switching between active transmitters and passive receivers, Bats restore their full hearing a split second later to listen for echoes.

Most of the more than 1300 species of bats use echolocation to hunt and navigate in poor lighting conditions. Fossil evidence indicates that this capability developed in bats at least 52 million years ago. They can detect an insect up to 15 feet away and determine its size, shape, hardness, and direction of travel through their skillful use of echolocation.

Wave Echoes

Animals have long been able to detect objects at a distance through the manipulation of nonvisible waves using technologies like radar and sonar or natural echolocation. Though each of these methods operates a little differently and relies on various shapes, sizes, and types of waves, they each work by emitting waves then determining characteristics based upon the echoes of those waves.

Try it at Home

Go to a corner of a quiet room and close your eyes. Without moving your body too much, try turning your head while making clicking noises with your mouth. Can you tell when you are turned more toward a wall or if there are any objects near you through the way the clicking sound changes? Try holding your hand up in front of your face and moving it back and forth while you click. Can you tell how far away it is or which direction it is moving by the sound? Get creative and try it with different types of objects and different locations!

Jane Thaler is a Gallery Experience Presenter in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Super Squid! Flying Marvels of the Natural World

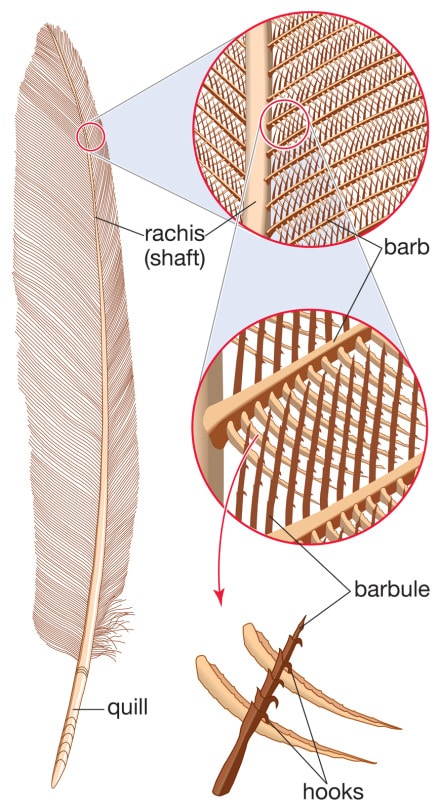

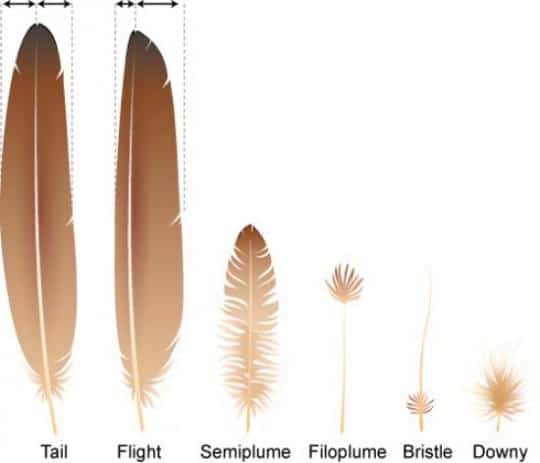

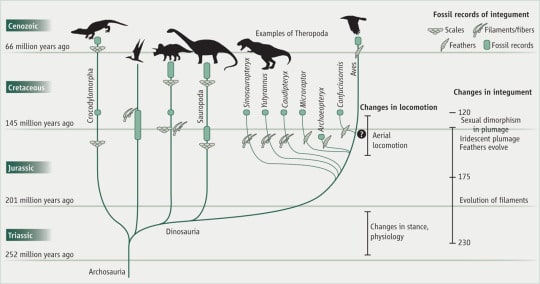

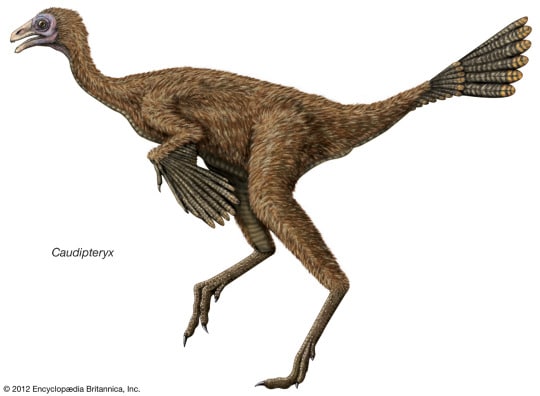

Fancy Feathers: An Unexplained Complexity in Evolutionary History

Ask a Scientist: What’s the difference between ravens and crows?