If you follow Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) on social media, then you may have seen a post announcing that Section of Vertebrate Paleontology (VP) Curator Emeritus Dr. Dave Berman and I, along with our collaborators, had recently published a new genus and species of caseid synapsid (a large lizard-like, very distant relative of mammals), Martensius bromackerensis, the specimens of which were discovered at the Bromacker quarry, central Germany. Dave and I are part of an international team from Canada, Germany, Slovakia, and the USA who have discovered, named, and described exquisitely-preserved fossils from the Bromacker quarry over the past 27 years. This recent publication most likely represents the last of the new Bromacker discoveries that Dave and I will publish on, due, in part, to the quarry having been closed to excavation for the past nine years.

With CMNH’s role in the Bromacker project winding down, and much of the world currently staying home and practicing social distancing, I thought this might be a good time to present the project’s highlights as a series of blog posts for you to enjoy. This post will introduce and present the history of the project, while topics of subsequent posts will include the discovery and collection of the fossils, fossil preparation, descriptions of the animals discovered, the geologic history of the quarry, and, finally, a summary of what we learned.

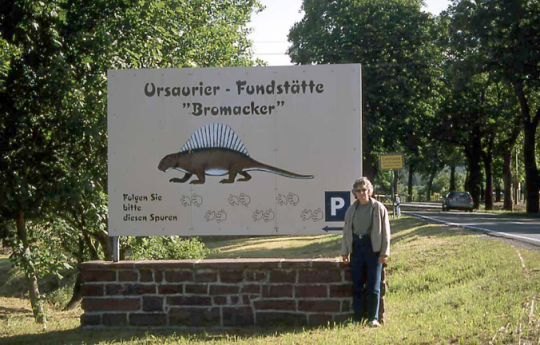

In the Bromacker area of Thuringia, central Germany, a thick rock layer known as the Tambach sandstone has been intermittently quarried for use as a building stone for more than 150 years. Evidence of life preserved in the Tambach sandstone in the form of tetrapod (four-footed backboned animal) footprints was discovered in 1887 and later studied by Professor Wilhelm Pabst from 1890 to 1908. Pabst was an amateur paleontologist who taught high school in the nearby city of Gotha.

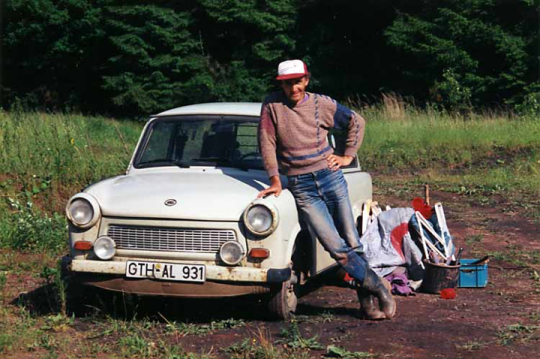

Dr. Thomas Martens (now retired Curator, Museum der Natur Gotha [MNG]) discovered the first vertebrate (backboned animal) body fossils at the Bromacker quarry in the summer of 1974. He was trained as an invertebrate paleontologist and was sent there by his major professor to look for fossils of conchostracans (‘clam shrimp’), a type of very small crustacean. After his first discovery, Thomas continued to collect at the Bromacker from 1975 to 1991, finding a variety of early Permian-aged (approximately 290-million-year-old) fossil vertebrates that were otherwise known only from North America. At that time, Thuringia was part of East Germany, so Thomas’ travel to other countries was restricted by his government, but fortunately he could communicate by mail with paleontologists overseas. He eventually began a correspondence with an expert on the types of fossils that he was discovering, CMNH’s Dave Berman (then Associate Curator). In 1992, two years after the reunification of Germany, CMNH sponsored Thomas to come to Pittsburgh to study with Dave for six months, which began a long and productive collaboration.

The Bromacker quarry is in the Thuringian Forest near the village of Tambach-Dietharz. It lies in a large field surrounded by thick forest traversed by dirt roads. People from the surrounding villages who regularly visited the Bromacker area to walk, ride their bikes, and pick wild mushrooms would stop to ask us what we were doing. School groups came regularly to learn about the fossil ‘diggings’ and to watch us work.

Field work at the Bromacker was conducted annually from 1993 to 2010 by Dave, Thomas, myself, and our other collaborators, which led to the discovery, collection, and scientific preparation and description of 13 fossil vertebrate species, 12 of which were new to science. Most of the fossils discovered were shipped to CMNH, where I prepared them in the paleontology lab in the museum’s basement. Once the fossils had been published in scientific journals, they would be shipped back to the MNG, because that museum is the legal repository for the Bromacker fossils. CMNH retained cast replicas made by VP staff of some of the more exquisite specimens, and some of these are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in the Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for these once the museum reopens. And stay tuned for my next post, that will describe how we found and collected the fossils!

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.