By Steve Tonsor

2500 years ago, Aesop wrote “We are known by the company we keep.” We experience the truth of this aphorism every day in our communities. Have you ever considered that our communities include more than our human company? (If not, take a spin through our exhibit We Are Nature before it closes September 3.)

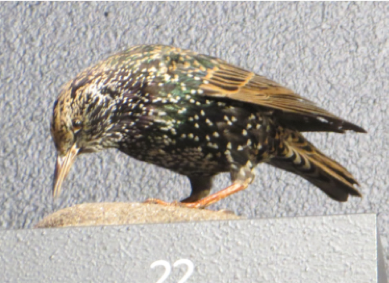

In recent times, we’ve talked as though we are walled off from the natural world, talking of “man vs. nature,” the “built urban landscape” vs. the “natural world.” Yet, urban centers teem with life, not the same life to be found in a wilderness, but a rich and fascinating web of life nonetheless. In fact, we aren’t even so numerically dominant in the urban ecosystem as we might think. For example, common starlings, purposefully introduced birds, are ubiquitous in urban settings and according to biologist Menno Schilthuisen1 are now about equal in number with humans in North America.

In a less purposeful way, we’ve invited in all the creatures in our urban communities, by providing what is necessary for their survival. The pigeons in our parks and urban squares were originally birds of Mediterranean and North African cliffs. After humans began to dwell in those cliffs, and then constructed cliff-like buildings, the pigeons moved with us into the nouveaux cliffs of the urban ecosystem. So it is with so many creatures, finding urban analogs to their wilder environments2.

We have invited in weeds by providing niches, literally in the urban concrete, and so they decorate the urban wastelands with the reminder that life will find a way. Are not the untended spots of the city more beautiful when adorned with weeds than they would be if old doorknobs and cigarette butts were the only decorations?

Over time, more and more creatures find a way into the emerging urban ecosystem. Whose cities are these? Our attitudes toward the new entrants has varied from laissez faire to downright hostile, yet these creatures are a reflection of our nature. We are known by the company we keep. We could be more accepting of our guests, and more deliberate and intentional about how we live and what creatures we as a consequence invite into our community3. Let’s talk about that.

21,Schilthuizen, Menno. 2018. Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution. MacMillan 304 pp. ISBN: 9781250127822

3 Cooper, C. B., J. Dickinson, T. Phillips, and R. Bonney. 2007. Citizen science as a tool for conservation in residential ecosystems. Ecology and Society 12(2): 11. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss2/art11/

Steve Tonsor is Director of Science at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.