by Erin Peters

If you visited our Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt in the last few weeks, you may have seen the windows and doors blocked so you couldn’t see inside. With this dramatic drapery, perhaps we were preparing a haunted Walton Hall for our October 26 After Dark? Alas, this is not the year of the mummy, but something mysterious was happening inside!

We are on the search for something missing from our Dynasty 12 funerary boat buried at the pyramid complex of Senwosret III. Even from this very spooky photo taken when we had the gallery blocked from light, you can see the boat is made of wood – cedar of Lebanon – a luxury good in the ancient world.

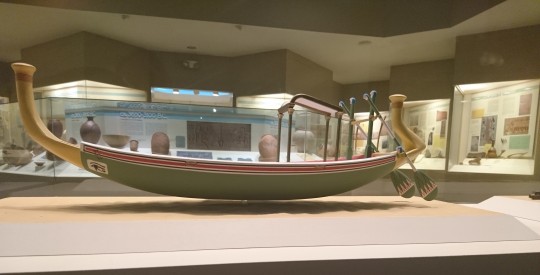

We know the boat was also painted because scholars that studied it in the 1980s noted small fragments of paint remaining on the wood surface. From these notes, they theorized it could have looked something like this model on display in the gallery.

We have new technology in the field of conservation that can reveal trace amounts of pigments that are not visible to the naked eye. To capitalize on this new technology, I invited my conservator colleague, Dawn Kriss, to work with CMNH’s conservator, Gretchen Anderson, to carry out Multi-Band Imaging on the boat.

With other sources of light blocked out, Multi-Band Imaging can reveal a number of elements on a surface including pigments, binders, and treatments, even if they aren’t easy to see. I am most excited about the pigment Egyptian blue, which can luminesce through Visible Induced Luminescence Imaging (VIL).

When Dawn found this mysterious blob – we thought we definitely had Egyptian blue!

In her analysis of the boat, Dawn first looked at the blob (with help from Chase Mendenhall, CMNH’s Assistant Curator of Birds, Ecology, and Conservation – moonlighting as an Egyptologist). Dawn carried out the whole range of Multi-Band Imaging on the blob, including VIL. Surprisingly, it did not luminesce like we all thought it would.

We invited our colleague, Michael Belman, CMOA’s Object Conservator, to join our hunt for information about pigments, binders, and treatments on the boat. My ultimate priority was the blob! When Michael tested it with XRF (X-Ray Fluorescence) technology, he found what seemed to be trace amounts of copper, which is what we would expect with Egyptian blue. Yet, there didn’t seem to be enough to suggest it was the primary element in the pigment…

This initial analysis has prompted us to continue our study of it, and search for other pigments, binding material, and treatments. Keep tuned for updates on the Carnegie Boat and the mystery of the blob!

Erin Peters is an assistant curator of science and research at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.