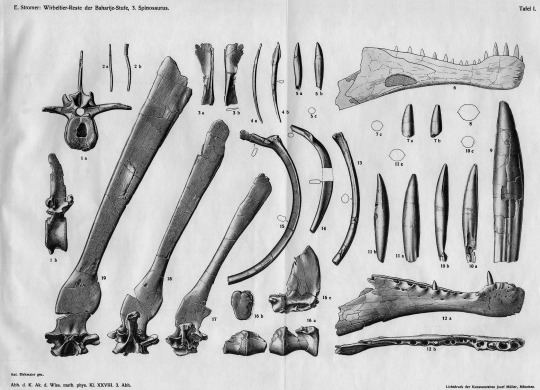

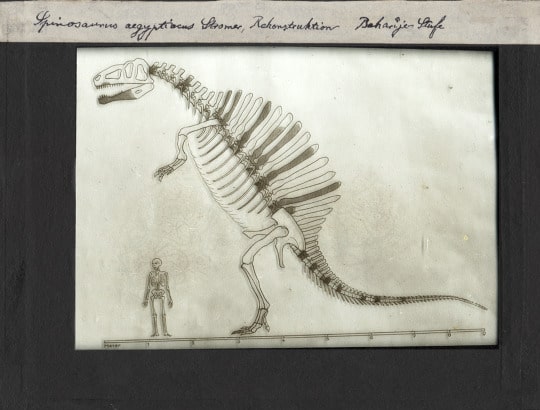

I’ve been captivated by dinosaurs for as long as I can remember. My parents tell me that I told them that I wanted to be a paleontologist as early as age four. Naturally, then, I had lots and lots of books about dinosaurs when I was a boy growing up during the 1980s. One of the dinosaurs that always fascinated me the most was Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Found in 1912 in the Bahariya Oasis of the Western Desert of Egypt (could anyplace sound more exotic to a small-town kid from upstate New York?!), Spinosaurus was originally known from a highly incomplete but also very large and extremely distinctive partial skeleton found in a middle Cretaceous-aged (roughly 95-million-year-old) rock layer in the oasis. Among the few skeletal elements known were part of a strangely shaped (for a dinosaur) lower jaw, some crocodile-like teeth, and most strikingly, several back vertebrae that each sported tall spines, some of them measuring nearly six feet. These spines clearly impressed Ernst Stromer von Reichenbach, the German paleontologist who studied the skeleton and gave the animal its name in a 1915 publication. Tragically, however, that original Spinosaurus skeleton—and all of Stromer’s other dinosaur fossils from Egypt—were destroyed during the Second World War, more specifically in a British Royal Air Force bombing of Munich on April 24, 1944. The story of Stromer’s lost dinosaurs found its way into many a children’s book, including several that I read cover-to-cover. As such, the tale took on near-legendary status for me, and, I’m sure, many other young dinosaur enthusiasts around the world. Here was an absolutely extraordinary dinosaur from a faraway land, similar in size to the gargantuan Tyrannosaurus rex, but clearly very different from all other predatory dinosaurs known at the time – and it was represented only by a few teeth and bones that had been blasted into oblivion decades ago and so now existed only as pictures in books.

When I arrived in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania in 1997, one of the first things I did was make a lengthy list of all the paleontological sites I was interested in exploring, ranked by their potential (in my mind, at least) to produce scientifically significant finds. The Bahariya Oasis and the search for a ‘replacement Spinosaurus’ quickly rose to the top of the list. Amazingly, no one had ever found—or at least officially reported—new dinosaur fossils in the oasis in the more than half-century since Stromer’s beasts were obliterated during that fateful airstrike. A need to keep this post to a reasonable length prevents me from describing the stars that had to align to make this happen, but in January 2000 I found myself in the Bahariya Oasis—one of the places I’d dreamed about going since I was a small child—as part of the first significant ‘dinosaur hunt’ to take place at the site since the early 20th century. It was bittersweet, though, in the sense that we never really found that ‘replacement Spinosaurus’ I’d fantasized about – all we ever discovered of that creature were a few isolated, fragmentary teeth and bones (and, in a very different location, a couple previously unpublished photos of the original skeleton in a Munich archive). We did find and dig up a gigantic new species of long-necked, plant-eating sauropod dinosaur, Paralititan stromeri, a creature that to this day is one of the largest land animals of any kind that’s ever been found, anywhere – but that’s another story for another time.

Back to the matter at hand, meaning Spinosaurus. Fast-forward to 2011. I had the honor of serving as the external thesis examiner for Nizar Ibrahim, a promising doctoral student at University College Dublin in Ireland. I’d known Nizar for years, ever since he reached out to me by email while an undergraduate at the University of Bristol, England, to discuss our mutual interests in African Cretaceous dinosaurs. Nizar’s Ph.D. thesis was on dinosaurs and other middle Cretaceous-aged vertebrates from the celebrated Kem Kem beds of southeastern Morocco, a set of rocks that had yielded a fossil fauna very similar to, though seemingly more diverse than, that of the Bahariya Oasis. Among the many finds that Nizar documented in his colossal thesis were intriguing new remains of Spinosaurus. I went to Dublin to participate in his successful thesis defense, and afterward, he and I hit up some of the city’s finest public houses to celebrate (no surprise for those who know me). Over a pitcher of yummy Irish stout, he told me an exciting story – he and his team had lately discovered not just isolated bones of Spinosaurus in Morocco, but parts of a probable new skeleton. If so, this find would be the first skeleton since Stromer, and moreover would be exceedingly important given how little was known about Spinosaurus, even as recently as the early 2010s. The more parts we paleontologists have of a given fossil animal, the more we can generally learn about it, so the prospect of a new and relatively complete Spinosaurus skeleton—in other words, many bones belonging to a single individual dinosaur—was thrilling to say the least.

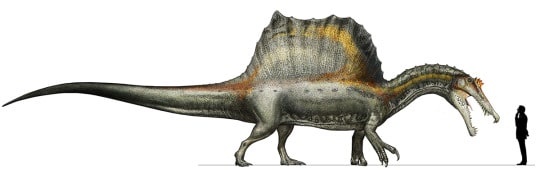

Again I’ll skip details for brevity’s sake, but fast-forward once again, to 2014. I was contacted by an editor of Science—one of the foremost scientific journals in the world—to peer-review a paper that had been submitted by (you guessed it!) Nizar and a long list of collaborators describing that new skeleton of Spinosaurus that he’d told me about over beers in Ireland three years before. Nizar and team had revisited the quarry and it had panned out in a big way. From this one, single individual Spinosaurus—again, the first associated skeleton of this dinosaur to have been found in roughly a century—they had bones from the skull, backbone (including a few of those famously long-spined vertebrae!), forelimb, pelvis, and hind limb. More importantly, these ‘new’ bones revealed that Spinosaurus was even more bizarre than anyone imagined! We already knew, from Stromer’s specimen and other, isolated finds made through the years, that the shapes of the skull and back were really weird for a predatory dinosaur. Now, the new skeleton showed that the bones were remarkably dense, the hind legs were oddly short, and the hind feet may have been webbed! All of this led Nizar and colleagues to propose that Spinosaurus may have been semiaquatic; in other words, that its lifestyle was much more comparable to that of a modern-day alligator or crocodile than it was to a more ‘typical’ land-living predatory dinosaur such as T. rex. Other evidence for an affinity to watery habitats had been found in Spinosaurus and closely related dinosaurs (known, perhaps unsurprisingly, as spinosaurids) before, but this was, in my mind, the most convincing case yet made that these animals spent significant amounts of their time at least partly submerged in lakes and rivers. The paper was published in Science a few months later, accompanied by a cover story in National Geographic magazine and a special on the venerable PBS TV series NOVA. Almost exactly one hundred years after it had been named, Spinosaurus had become a celebrity.

But the story didn’t end there. Some prominent paleontologists criticized Nizar and colleagues’ semiaquatic interpretation of Spinosaurus. These opinions weren’t a final judgment. Instead, this is just how science works: we scientists propose ideas, or hypotheses—in this case, that Spinosaurus lived and behaved more like a crocodile than your garden-variety carnivorous dinosaur—and then test these hypotheses by reevaluating the existing evidence and/or bringing new information to light. If a hypothesis repeatedly stands up to testing, then it gradually gets incorporated into the body of knowledge. Other paleontologists presented evidence that they claimed refuted the semiaquatic hypothesis, but Nizar and team eventually countered with new data of their own. In late 2019, another prominent scientific journal—this time it was Nature—came calling, asking me to review a second paper by Nizar et al. on Spinosaurus. What, I thought, could these researchers have to say about this dinosaur that they hadn’t already said before? Well, as it turns out, Nizar and colleagues had kept digging at their Spinosaurus skeleton site, and incredibly, they’d continued to find important new bones belonging to the same specimen. Among these post-2014 finds was the almost complete tail. When I saw what it looked like (via an illustration in their paper), I literally laughed out loud with surprise and delight. Somehow, the shape of the Spinosaurus tail Nizar’s team had discovered—the first even reasonably complete tail of this dinosaur to have ever been unearthed—was simultaneously both unexpected and predictable. It looked really dissimilar from the tails of other predatory dinosaurs, but it was nearly exactly like what one might expect for a dinosaur that used its tail to propel itself through water. In other words, the tall, fin-like tail of Spinosaurus looked more like that of a supersized alligator or newt than that of T. rex.

Nizar and team’s Nature paper on their Spinosaurus tail was published this past April 29. Is it the last word on this dinosaur and its mode of life? Most certainly not, but the evidence is now stronger than ever—in my opinion, very strong—that Spinosaurus spent more time in the water than any other non-avian (= non-bird) dinosaur that we currently know about.

Nizar (who’s a Research Associate here at Carnegie Museum of Natural History), myself, and our many colleagues and collaborators are continuing to study the mysterious dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates from the middle and Late Cretaceous of northern Africa. Indeed, Nizar and I have several collaborative papers in the works right now, and I’m also working with an amazing team of paleontologists at Mansoura University on multiple new Egyptian fossil finds. It’s a good bet that African Cretaceous dinosaurs even stranger than Spinosaurus are still out there, waiting to be discovered!

Further reading/watching:

Nothdurft, W. E., with J. B. Smith, M. C. Lamanna, K. J. Lacovara, J. C. Poole, and J. R. Smith. 2002. The Lost Dinosaurs of Egypt. Random House, New York, 256 pp.

Smith, J. B., M. C. Lamanna, H. Mayr, and K. J. Lacovara. 2006. New information regarding the holotype of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus Stromer, 1915. Journal of Paleontology 80:400–406.

Ibrahim, N., P. C. Sereno, C. Dal Sasso, S. Maganuco, M. Fabbri, D. M. Martill, S. Zouhri, N. Myhrvold, and D. A. Iurino. 2014. Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur. Science 345:1613–1616.

Bigger Than T. rex (NOVA documentary): https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/bigger-than-t-rex/

Henderson, D. M. 2018. A buoyancy, balance and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda). PeerJ 6:e5409.

Ibrahim, N., S. Maganuco, C. Dal Sasso, M. Fabbri, M. Auditore, G. Bindellini, D. M. Martill, S. Zouhri, D. A. Mattarelli, D. M. Unwin, J. Wiemann, D. Bonadonna, A. Amane, J. Jakubczak, U. Joger, G. V. Lauder, and S.E. Pierce. 2020. Tail-propelled aquatic locomotion in a theropod dinosaur. Nature 581:67–70.

Matt Lamanna is Mary R. Dawson Associate Curator and Head of the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.