As an intern in the Anthropocene section at the Carnegie Museum, I had the privilege of exploring some of its treasures, either preserved in the collections or displayed for the public, and reflecting on how objects can help us consider the planetary changes underway in the Anthropocene.

During my explorations, I was asked what was my highlight, or what object best exemplifies the Anthropocene to me?

Turns out – my most vivid symbol of the Anthropocene is absent. It is not found in either the collections, or in the gallery halls (although it is found in the cafeteria)!

Yes indeed, my favorite symbol is the commercial broiler chicken, likely one of the most common birds in the world because it reaches slaughter weight in less than half the time of other domestic or wild chickens! Surprised? Disappointed? Let me explain…

Last year, the director of the museum, Dr. Eric Dorfman, wrote a compelling blog titled Counting Your Chickens: The World’s Most Numerous Bird. Chickens are likely the most numerous bird in the world. In light of the Anthropocene, we could even say in Earth history. There are about 23 billion chickens alive at any given time. By comparison, the second most numerous bird reported is the red-billed quelea, which lives across the continent of Africa, with an estimated population of 1.5 billion.

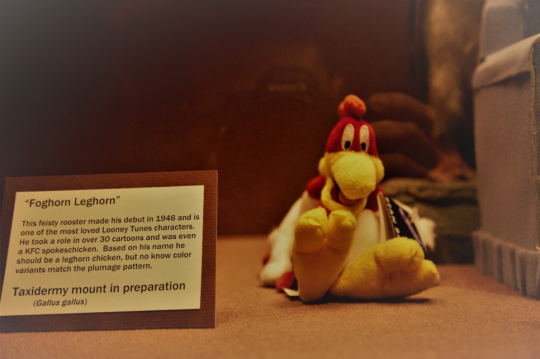

You probably wonder how the chicken conquered the world. Its long journey began around 7,000 years ago when it was first domesticated from the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus), native to south-east Asia. But the bird’s trajectory radically changed in the second half of the 20th century, during what is now called “The Great Acceleration.” With changes in farming practice and the intensive production of broilers, the chicken population exploded. Meat-chicken consumption is still on the rise with more than 65 billion chickens consumed globally in 2016.

The commercial broiler chicken is even more radically different from its ancestors and other kinds of chickens. The change is about their shape, genes, and chemistry. Their genes, for instance, have been altered so that the birds are constantly hungry. In other words, they have been bred for a specific purpose: to gain weight rapidly (and they do it five times faster than chickens from the mid-20th century). It is a perfect example of what Richard Pell, director of the Center for PostNatural History and Associate Professor of Art at Carnegie Mellon University, means by the term “postnatural,” that is an organism that has been intentionally and heritably altered by humans.

The commercial broiler chicken is the direct result of human intervention. One could argue that selective breeding practices are not new. However, the Anthropocene captures a very recent rupture in Earth’s history by highlighting rapid and unprecedented changes at a planetary scale. Commercial broiler chickens and their biology shaped by humans, created in just a few decades, symbolize the transformation of the Earth’s biosphere. And new research suggests that the commercial broiler chicken’s distinctive bones could become fossilized markers of the Anthropocene. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to talk about the Gallucene.

Stories like this show how the Anthropocene offers an opportunity to rethink how we view natural history and what we put in our collections. The Carnegie Museum of Natural History is undertaking this ambitious and necessary shift in order to understand what it means to live in this new epoch.

Gil Oliveira is an intern in the Section of the Anthropocene. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.