by Patrick McShea

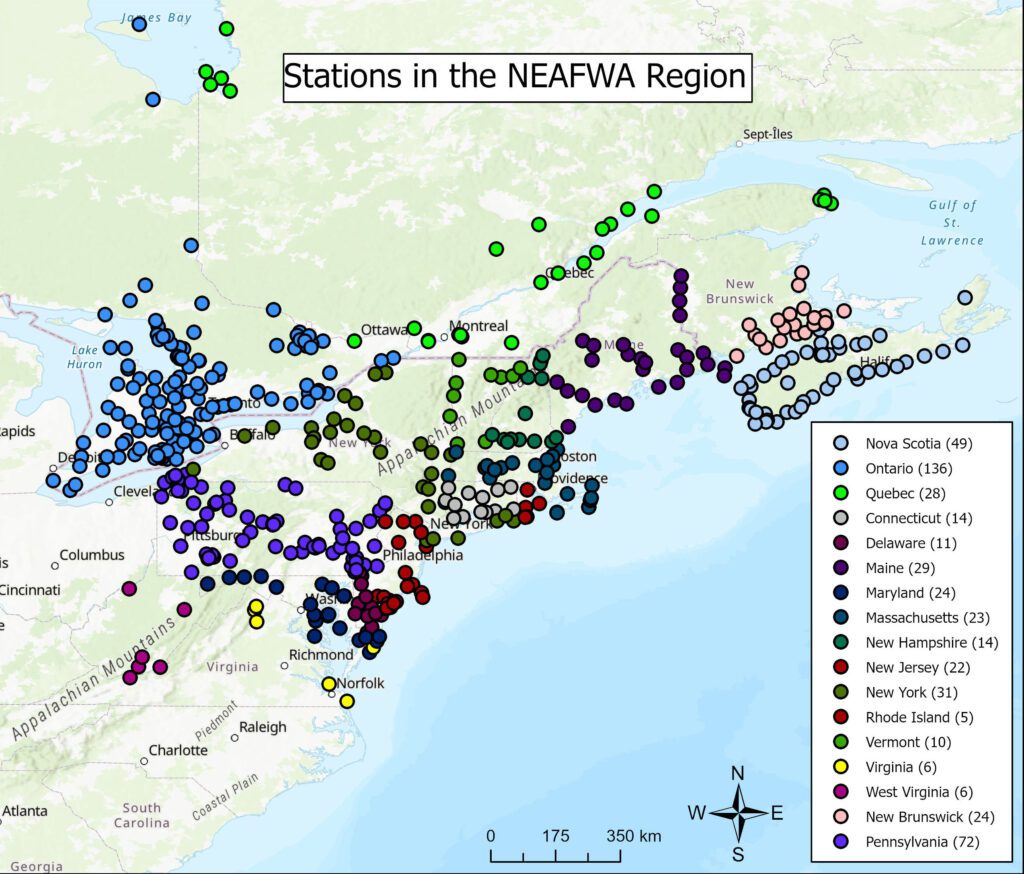

Explanations of networks benefit from maps or other graphic representations of linked participants. In the case of a recent bulletin describing regional growth within the international research network known as the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, the inclusion of a map helps ground updated information about the program to the landscape.

The collaborative effort, known informally as simply Motus, a Latin word for movement, was founded by the bird conservation organization, Birds Canada in 2014, and has grown to involve hundreds of partners among scientific and educational institutions, government agencies, and independent researchers.

The ground-breaking work of Motus involves the use of automated radio telemetry to track the migratory movements of free-flying birds, bats, and insects. After an animal under study is safely captured, fitted with a highly miniaturized transmitter, known as a nanotag, and released, the creature’s flight movements are electronically detected and recorded whenever it passes within nine miles of strategically placed antennas mounted on low, just-above-tree-canopy-height receiving stations.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History is a Motus partner through the work of staff at its Powdermill Avian Research Center who have installed 136 receiving stations from western Maryland through Maine and continue to monitor 50 receiving stations from southwestern Pennsylvania up through western New York along the Adirondack Mountains.

Although Motus stations are in place across the Western Hemisphere landmass from Nunavut, Canada, to southern Chile, the world’s densest concentration of them is found in the thirteen U.S. states and five Canadian provinces that make up the network’s Northeast Collaboration. The 504 tower sites in this territory represent one third of the global total, and since 2017 have logged more than 170 million nanotag detections. This tracking has involved more than 4,700 tagged individuals of 147 species of birds contributing vital information to 194 different research projects.

Ongoing maintenance and technological upgrades will be necessary for the Northeast Motus Network to continue generating research findings that inform conservation initiatives. As Jon Rice, the Museum’s Urban Bird Conservation Coordinator explains, “As this network reports findings for museum research into both the survivorship of window collisions and stopover behavior for species of greatest conservation need, it simultaneously supports ongoing research for countless other projects in the western hemisphere. The real power of this technology isn’t captured by the map. It’s our ability to help our neighbors using the same resources we are using to perform our own novel research.”

Patrick McShea is an Educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Milestones at Powdermill’s Banding Lab

Ruffed Grouse or Scarlet Tanager: Debating the Pennsylvania State Bird

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: July 17, 2023