by Albert D. Kollar, Collection Manager, with assistance from Suzanne Mills, Collection Assistant, and Joann Wilson, Volunteer Section of Invertebrate Paleontology

The exhibits of Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Carnegie Museum of Art are ideal for a multidisciplinary study of fossil fuels in Pennsylvania and beyond. Such a study must properly begin with some historical background about the landmark Oakland building that houses both museums, as well as some background information about fossil fuels.

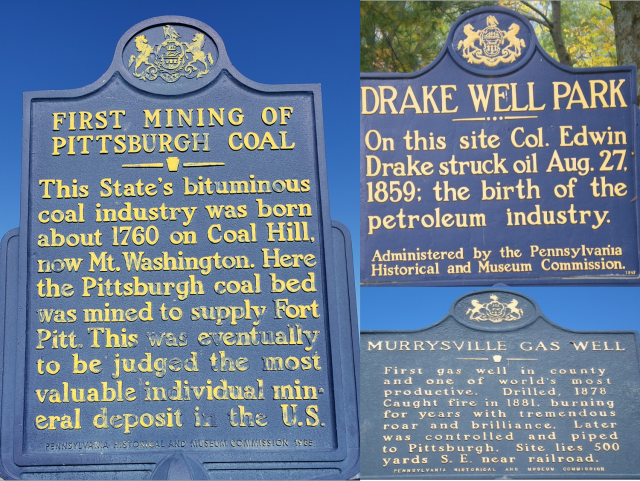

When the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh opened in 1895, the architects, Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow incorporated roof skylights for maximum daytime lighting in the Italian Renaissance designed building1. Nighttime activities were illuminated by interior gas lighting fixtures, possibly supplied by the Murrysville gas field, which began production in 1878. With the opening of the Carnegie Institute Extension in 1907, the Bellefield Boiler Plant was built in Junction Hollow to supply in-house steam heat and electricity from bituminous coal1. From the 1970’s, coal and natural gas had been used to heat the boilers that supply heat to the Oakland Campus, Phipps, the University of Pittsburgh and the Oakland hospitals. In 2009 coal was eliminated as a fuel source. Electricity on the other hand, is supplied through Talen Energy from multiple sources (coal, gas, and renewal energy sources). For the future, Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh plans to receive its electricity from renewable solar energy via Talen Energy2.

What are Fossil Fuels?

Coal, oil, and natural gas (methane), known collectively as fossil fuels, are sources of energy derived from the remains of ancient life forms that usually are found preserved in coal rock, black shale, and sandstone.

Coal is a rock. The coalification process starts from a thick accumulation of plant material in reducing environments where the organic matter does not decay completely. This deposit of plant residue that thrives in freshwater swamps at high latitudes forms peat, an early stage or rank in the development of coal. With the burial of peat over geologic time and a low temperature form of metamorphism produces a progression of the maturity or “rank” of the organic deposits that form the coal ranks of lignite, sub-bituminous, bituminous, and anthracite)3 (Fig. 1). The Pennsylvanian Period was named for the rocks and coals of southwestern Pennsylvania that formed more than 300 million years ago.

Oil and natural gas, collectively known as hydrocarbons, were forming in the Devonian rocks of Pennsylvania between 360 and 390 million years ago. These hydrocarbon deposits or kerogens are made of millions of generations of marine plankton and animal remains that accumulated in a restricted anoxia ocean basin that extended from southern New York, through western Pennsylvania, northern West Virginia to eastern Kentucky4. The thick layers of sediment formed black shales or mud rocks such as the Marcellus Shale. Black shales are rich in oil and gas and are called source rocks. Sandstones such as the Oriskany Sandstone that is older than the Marcellus Shale is a reservoir rock. An amorphous mass of organic matter or kerogen undergo complex geochemical reshuffling of the hydrocarbon molecules first with burial then by thermal “cracking” as heat and pressure through the geologic process of metamorphism over millions of years transform kerogen into modern day fossil fuels4.

Fossil Fuels in Modern Society

As commodities converted to fuels for our modern world, these resources account for 80% of today’s energy consumption in the United States5. All three fossil fuels, in furnaces of vastly different design, have been used to directly heat homes, schools, workplaces, and other structures. In power plants, all three have been used for generating electricity for lighting, charging mobile phones, and powering computers, home appliances, and all manner of industrial machines. In the United States, , coal became the country’s primary energy source in the late 1880s, displacing the forest-destroying practice of burning wood. It ceded the top spot to petroleum in 1950 but enjoyed a late-20th-century renaissance as the primary fuel for power plants5. Coal now generates approximately 11% of our country’s supply down from 48% just 20 years ago. Natural gas is currently used to generate approximately 35% of US electricity supplanting the use of coal6. While petroleum is less than1%6.

Transportation accounts for approximately 37% of total energy consumption. Coal played a historic role in powering railroads, and both compressed natural gas and batteries (charged with electricity generated from various sources) are of growing importance, however, refined oil products currently power 91% of the transportation sector6.

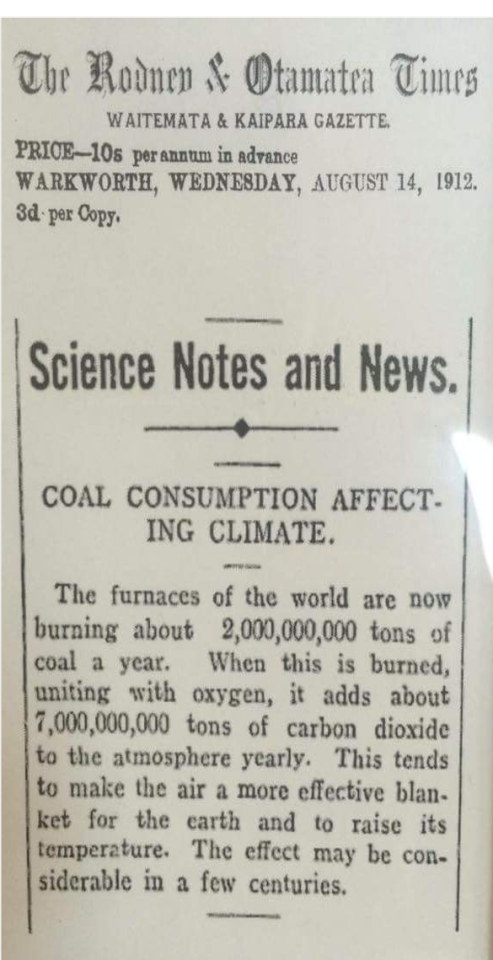

In the early 20th century, scientists warned about how the burning of coal could create global warming in future centuries by raising the level of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse or heat-holding, gas, in the atmosphere. (Fig. 2 ). It took less than a century for evidence to mount of climate change associated with the burning of fossil fuels, the clearing of forests associated with industrial scale livestock production, and from waste management and other routine processes of modern life. In recent decades headlines have routinely proclaimed the risks of a warming planet, including damage to terrestrial ecosystems, the oceans, and a rise in sea level7.

Fossil Fuels and Museum Geology Displays

When architects Frank E. Alden and Alfred B. Harlow designed the Carnegie Institute Extension (1907), they incorporated Andrew Carnegie’s vision to create an introduction hall to the museum named Physics, Geology and Mineralogy8. This hall (the forerunner to Benedum Hall of Geology) was intended to introduce Pittsburghers to the regional natural history subjects of geology, paleontology, and economic geology (fossil fuels)9.

In the 1940s, the 300-million-year-old Pennsylvanian age coal forest diorama was installed in a corner space of what is now part of the Benedum Hall of Geology (Fig. 3). Because coal converted to coke is a vital ingredient in steel production, this three-dimensional depiction of the conditions under which Pittsburgh’s economically important coal deposits formed was (and remains) an important public asset.

In 1965, as part of an overall plan to bring more of the natural history museum’s fossil collection to the public, Paleozoic Hall opened with funding from the Richard King Mellon Foundation10. This exhibition featured nine dioramas that recreate the ancient environments through 290 million years of Earth history. Sadly, only one of the nine units remains on display, the diorama depicting the Pennsylvanian age marine seaway (Fig. 4 ), in the Benedum Hall of Geology.

Since the Benedum Hall of Geology opened to the public in 1988 the exhibition has featured an economic geology component with displays explaining differences between coal ranks Lignite coal to anthracite coal, and a variety of Pennsylvania’s crude oils and lubricants processed from the historic well Edwin Drake drilled in Titusville in 1859 (Fig. 1 )11.

Today, the Hall’s “strata wall,” a towering depiction of some of the rock layers found thousands of feet below western Pennsylvania, is in my opinion, an under-utilized display in terms of conveying information about fossil fuels. Although the wall is not currently documented with any geologic information, minor changes might allow visitors to use the lens of rock strata to better understand historical events such as the Drake Well, and economically important geologic reservoirs such as the Marcellus Shale (the second largest gas deposit in the United States), the natural gas storage reservoir of the Oriskany Sandstone, and the gas and liquid condensate (ethane) extracted from the Utica Formation (Ordovician Age) for making plastic products at the Shell Cracker Plant in Beaver County, PA (Fig. 5 ).

Elsewhere in the museum, visitors can learn more about the topic of fossil fuels at several other locations. At the Holzmaden fossil exhibit in Dinosaurs in Their Time, there is a large fossil crinoid preserved in a dark gray limestone of Jurassic age, that represents a reservoir of crude oil in Germany (Fig. 6). At the mini diorama of the La Brea tar pits, oil seeps from natural fractures from an approximately six-million-year-old rock of Miocene age, to the unconsolidated surface sediment in what is now part of the City of Los Angeles (Fig. 7).

Looking for Fossil Fuel Evidence in Art

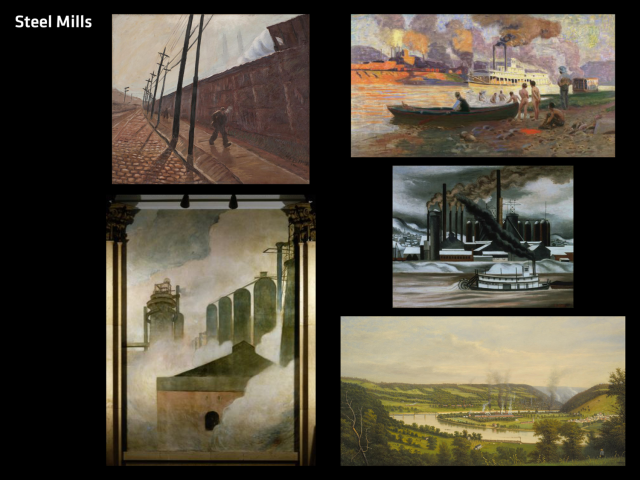

In 2018, I reviewed 58 landscape paintings and the John White Alexander wall murals on the first and second floors of the Grand Staircase within Carnegie Museum of Art (CMOA) galleries to look for artistic documentation of what I interpreted to be causes for climate change based on the science. I found many examples based on the use of coal as a fossil fuel for power and coking in steel mills and the natural formation of bio-methane as portrayed in ecosystem landscapes of the industrial age of the middle 19th and early 20th century12.

Searching for the CMOA landscapes paintings takes a little patience, but the visitor is rewarded by taking a new look at some of the art museum’s classic paintings (Fig. 8 and 9).

Within day trip visiting distance of Carnegie Museums are historic plaques highlighting the discovery of coal on Mount Washington, natural gas in Murrysville, and oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania. (Fig. 10). At all three stops you’ll have a better understanding of the significance if you begin your investigation of fossil fuels at Carnegie Museums.

Albert D. Kollar is the Collection Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Suzanne Mills is the Collection Assistant and Joann Wilson is a volunteer Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

References

- Kollar, A.D. 2020. CMP Travel Program and Section of Invertebrate Paleontology promotes the 125th Anniversary of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh with an outdoor walking tour. https://carnegiemnh.org/125th-anniversary-carnegie-library-of-pittsburgh-outdoor-walking-tour/

- Personal communications Anthony J. Young, Vice President (FP&O) Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

- Brezinski, D. K. and C K. Brezinski. 2014. Geology of Pennsylvania’s Coal. PAlS Publication Number 18.

- Geology of the Marcellus Shale. 2011. Brezinski, D.K., D. A. Billman, J.A. Harper, and A.D. Kollar. PAlS Publication 11.

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-03/coal-consumption-in-the-u-s-declines-as-natural-gas-solar-wind-energy-rise

- United States Energy Agency (EIA) 2019.

- Bill Gates. 2021. How to Avoid A Climate Disaster.

- Kollar et al. 2020. Carnegie Institute Extension Connemara Marble: Cross-Atlantic Connections Between Western Ireland and Gilded Age Architecture in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. ACM, 86, 207-253.

- Dawson, M. R. 1988. Benedum Hall of Geology. Carnegie Magazine, 12-18.

- Eller, E. R. 1965. Paleozoic Hall. Carnegie Magazine, 255-338.

- Harper and Dawson 1992. Benedum Hall-A Celebration of Geology. Pennsylvania Geology, 23, 12-15.

- Kollar et al. 2018. Geology of the Landscape Paintings at the Carnegie Museum of Art, a Reflection of the “Anthropocene” 1860-2017. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs, v. 49, 243.

Related Content

The Story of Oil in Western Pennsylvania: What, How, and Why?

The Giant Eurypterid Trackway: A Great Fossil Discovery on Display

Cities Are Not Biological Deserts

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Kollar, AlbertPublication date: May 5, 2021