By Chase D. Mendenhall

What came first, the chicken or the egg? The answer to this riddle is the egg. Eggs are universal among all vertebrates, including humans, but reptiles are responsible for the development of the eggshells typical of terrestrial birds and early mammals. Eggs are virtually self-contained life support systems that freed the first reptiles to wander away from water for reproduction, separating them from amphibians. Eggs are packed with most of the ingredients needed to grow the animal inside. All they require for the embryo to develop properly are warmth and gas exchange.

Bird eggs vary tremendously. Shape, size, coloration, and contents have often been associated with life histories of the species that lay them. For example, asymmetrical eggs with one pointed end were thought to be the result of nesting on a cliff—these eggs roll in tight circles instead of straight off the edge. Similar stories have been written about extensively to explain the jelly bean shape of the hummingbird eggs, elongated ellipses of swifts, and the spherical nature of owl eggs—but new work done in museum collections may have answered the riddle of egg shape definitively. Specifically, scientists now have evidence to suggest that selection for flight adaptations is most likely to be responsible for most of the variation.

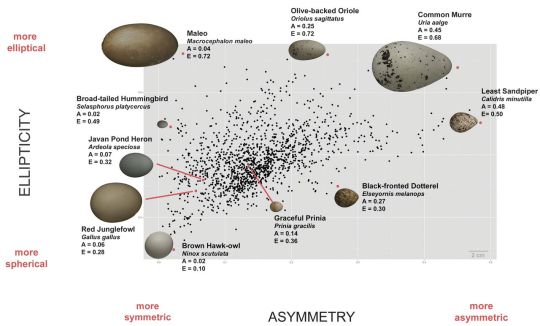

Measurements of nearly 50,000 eggs in museum collection from 1,400 bird species by Dr. Mary Stoddard and colleagues revealed stunning evidence that egg shape is related to flight. Dr. Stoddard’s star variables for testing her hypothesis were egg asymmetry and ellipticity. Symmetric eggs have similar shapes at each end, like the hummingbird’s jellybean shaped eggs, and asymmetric eggs are pointed at one end, like a sandpiper egg. Ellipticity is related to length and volume of the egg—for example, owls lay spherical eggs, while Orioles and Swifts lay long zeppelin-shaped eggs. The two variables of asymmetry and ellipticity interact with one another, allowing scientists to categorize egg shape across two axes that provide information about the way the egg was shaped in the shell gland after passing through the uterus.

Stoddard discovered that mother birds shape their eggs mechanically, apply pressure to the egg membranes as layers of calcium carbonate crystals form the eggshell. The shape of the egg determines the space in which the young bird completes the process of building its body for flight. Like all multi-cellular vertebrates, one cell divides into many—differentiating into trillions of cells with specialized architecture and function. According to Stoddard’s analysis of egg shape in relationship to phylogenetic history, she was able to demonstrate that egg shape explained wing shape. Spherical eggs, like those of the owl, are symmetric and score low on the ellipiticity scale and tend to belong to birds who spend little time flying. Elongated, asymmetric eggs—like those belonging to sandpipers, are associated with champion flyers who might spend many days airborne.

Chase Mendenhall is Assistant Curator of Birds, Ecology, and Conservation at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.