Agriculture is many things when it comes to climate change: a source of heat trapping gases, a casualty of extreme weather events, and part of the solution. At Carnegie Museum of Natural History, we’re working with rural communities in western Pennsylvania to talk about climate change in conversations that connect the dots between agriculture as a source of emissions, a sector of vulnerability, and an under explored reservoir of much needed solutions. This work is happening through the Climate and Rural System Partnership (CRSP, which we pronounce “crisp”), a National Science Foundation-funded program involving three CMNH components (the Education Department, the Section for Anthropocene Studies, and Powdermill Nature Reserve), partner researchers at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Learning Out of School Environments, and the Mercer County Conservation District. In CRSP, we are using methods of co-production and co-design to develop climate change science and communication resources with our community partners that are relevant to the lived experiences and concerns of those partners’ and their audiences.

How is climate change impacting farmers in western PA? What would help them to make adaptive planning decisions? What mitigation actions are most attractive to western PA farmers and will best help to sustain livelihoods into the future? Are Western PA farmers already, or interested in becoming, climate champions–leading their community in mitigating and adapting to climate change on their farm? How can the museum help? These are some of the questions we are exploring in CRSP.

Working alongside local livestock and row crop farmers, Penn State agriculture extension educators, and representatives of the Natural Resource Conservation Service (the agency formerly known as the U.S. Soil and Conservation Service), and the Mercer County Conservation District (a CRSP network hub), I have the privilege of exploring these issues and co-producing useful communication resources. Co-production is an iterative collaboration involving diverse perspectives to produce locally relevant knowledge and solutions (Norstrom et al 2020, Meadows 2015). Instead of scientists being the sole creators of new knowledge, in co-production all are creators of new knowledge.

CRSP partners and I have started by developing an agriculture working group at the Mercer hub (also called the Shenango Climate and Rural Environmental Studies Team or Shenango CREST). In this group, we have compiled climate thresholds, which are climate data types that are meaningful to the everyday lives of farmers in Shenango River Valley. Global averages are not applicable here, instead we’re looking for things that affect farmers’ decision making or impacts the physical conditions required to operate. To do this, I asked the group “How do we make existing climate data, past and present, most useful? What connects climate to the everyday life of a farmer of both row crops and livestock. What is going to mean something when we talk with farmers in the Mercer area?“ Some of the thresholds that the group identified were: too much rain in the spring for planting crops, too much rain in the fall for harvesting the crops, and warmer winters in which the ground does not freeze leading to problems for soils and livestock.

Here’s an example of how the co-production process works. First, I found the best available data from 11 rural weather stations in the western PA region, each with 80-100 years of daily rainfall and temperature measurements, obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency’s Climate Data Online tool. Then, one of the network members identified a climate threshold as how the “July and August heat hurts milk production.” So, I explored the data to see what is happening with summer heat in rural western PA: has it been getting hotter? Will this continue in the future?

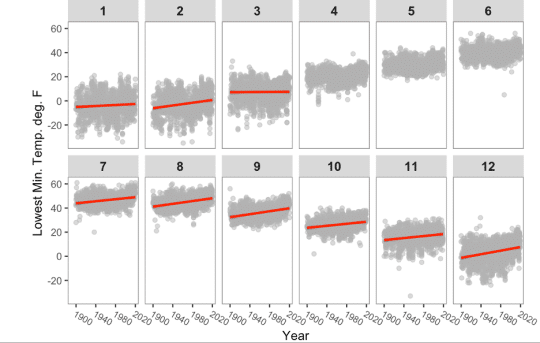

The short answer is yes. One analysis I used to explore these questions looks at the daily minimum temperatures. Warming daily minimum temperatures would mean less relief at night for the livestock as well as for crops. So, I conducted statistical analyses, and created a “rough draft” data visualization showing the minimum temperatures per month and the increasing trend over time in all months except April, May, and June (see figure below).

Regarding dairy cows in the summer heat, this analysis revealed that since 1900 the coolest August nights have warmed 7oF in our region. Upon seeing this, one of the network members said, “Really great, local data, people can feel like they can trust it.” Another reacted, “Interesting to take a piece of climate change, make it understandable and relatable. Put science to something already happening, a thing they [farmers] are living.” The visualization prompted talk of impacts on milk production as well as changes in calving time, lambs needing shearing more often, and with soils not freezing as much in the winter, hooved animals face a potentially greater parasite load from the mud in the warmer months.

This successful first iteration of CRSP co-production suggests we are identifying climate trends with which local farmers can personally identify. Into the future, climate projections for low and high emissions scenarios show the number of days per year over 90oF in Mercer County increasing, and highlights how mitigation of climate change now will reduce that increase in temperature.

With these kinds of analyses, the Mercer agriculture working group is aiming for evidence-based and locally relevant outputs in the form of talking points, maps, and graphs about climate change impacts and solutions. We will also collect personal stories of network members and people they know that illustrate a shared experience among people in the region and a hopeful message of climate adaptation and/or mitigation.

Impacts of this work, we hope, will be to bring the narrative about climate change from insurmountable, global, and blaming, to a community-scale conversation that is tractable, local, and hopeful. Within the museum itself, this work will help us better understand how to better serve rural audiences, bridge rural and urban connections (not divisions), and have productive conversations about socio-scientific issues that cut through politicization and misinformation. The diverse connections between climate change and food production provides a “ripe” opportunity to explore how to have such conversations.

Bonnie McGill is a science communication fellow in the CMNH Anthropocene Section. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Works cited:

Norström, A.V. et al. 2020. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nature Sustainability 3:182-190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2

Meadow, A.M. et al. 2015. Moving toward the Deliberate Coproductin of Climate Science Knowledge. Weather, Climate, and Society 7:179-191. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-14-00050.1

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is an amphibian party?