Spring is just around the corner, even if it doesn’t feel like it the last few days. In the Laurel Highlands, the trout lilies and trillium are blooming, the closed umbrella forms of May apples are poking through the leaf litter, and the migrating birds are on their way. Some are already here. For many birders, spring is the most exciting time of year. We’ve waited months to see something different, all dressed up fancy and bright after growing new feathers over the winter. We also get a chance to see some birds as they lay over, northward bound to the boreal forest or arctic tundra. So, when will they be here? That depends on two things: time and wind.

Birds want to arrive as soon as there’s food to eat so they can stake their claim on a nice plot of land to raise a family. Since the tundra is still frozen, birds that breed there, like the Grey-cheeked Thrush, won’t be coming until around the second week of May. Louisiana Waterthrushes on the other hand, arrived the beginning of April, as soon as insects were flying along the mountain streams they call home. Both species know when to depart their wintering grounds based on daylength, honed over thousands of years through natural selection.

Gray-cheeked Thrush

Louisiana Waterthrush

The other thing birds base their decision to leave upon is weather, specifically wind. And it effects how many migrants might be arriving on a particular day at a particular place. Put another way, birds’ instincts effect the range of dates they arrive, weather influences the specific dates.

How is wind important? Hawks soar using thermals (warm air rising from heated land masses) or ridges (wind pushed up by ridges). Songbirds on the other hand, migrate at night and fly when the winds are light or are in the direction they are heading (when they literally have a tail wind). Because low pressure systems spin counter-clockwise fall migrants will move after a low front passes in the fall or before a low front arrives in the spring. We like to use Hint.fm wind maps to help predict when and where migrants can move. Besides being informative, these maps show the beautiful complexity of wind patterns.

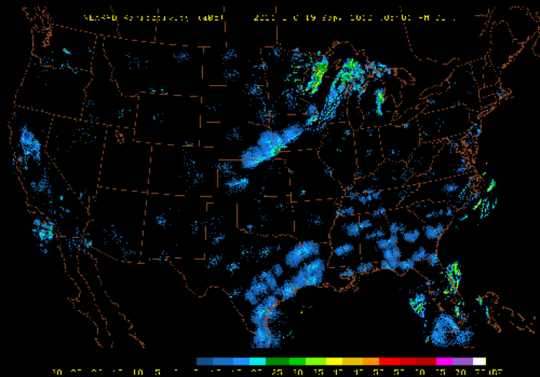

You might now be wondering how we use these maps. Let’s use Sept 19th, 2012 as an example. At 1pm EST there are light, southerly winds along the eastern seaboard and throughout the Southeast. There are also strong southerly winds in the western part of the Midwest. If you imagine that these patterns will slowly move eastward (say half an inch by sunset) you might predict strong migration for the eastern seaboard, the southeast, and the Midwest.

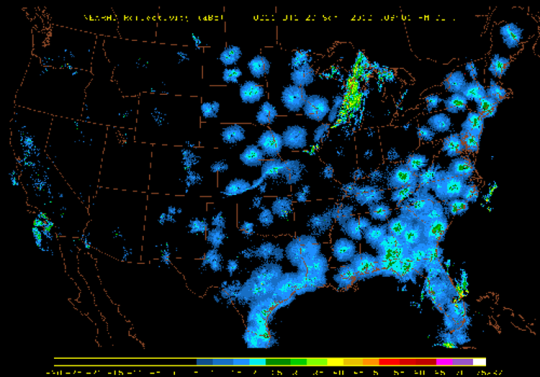

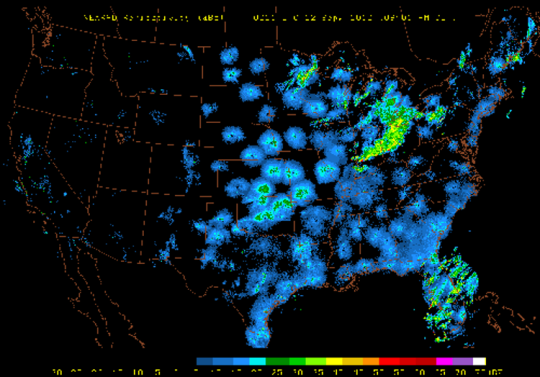

If you made such a prediction you would be right, but you don’t have to take our word for it. It turns out that birds taking off and migrating at night are picked up on radar. Here’s a radar loop from 5pm EST Sept 19th to 1:40am EST Sept 20th. At the very beginning you can see storm systems across Wisconsin and Iowa. As the frames progress you can see intense circular “clouds” appearing across the east, Southeast, and Midwest. These “clouds” are millions of birds taking off after sunset and continuing to migrate throughout the night. They’re circular because they are centered around each radar. We call these appearances “blooms” because they blossom around the radar sites.

Notice that where the storm system is and several hundred miles to the east (about an inch) there aren’t any blooms. That’s because this is the area which is experiencing strong northerly winds. Rather than fighting the headwind, birds in this area are staying put until more favorable winds come through. The winds along the gulf appear to be favorable for a trans-gulf crossing and you can see the clouds of birds take off and begin to move off the gulf coast shoreline (especially Texas). Looking at the longer loop from 3pm EST the 19th to 2pm EST the 20th you can also see birds taking off in Illinois and Iowa after the front has passed through.

What about the spring you ask? Remember, since the low-pressure systems spin counter clockwise birds migrate ahead of a front. A few days ago, the night of April 11th, there were southerly winds resulting in good movement northward across the southeastern U.S. Looking ahead, the next significant warm-up with nightly, light, southerly winds won’t occur until next week, mid-week (around Tuesday April 21st). If piecing together wind patterns and radar isn’t your thing, Cornell Lab of Ornithology has you covered. They’ve put together something they call BirdCast which puts combines weather, radar, and bird data (ebird) to forecast bird migration for the U.S.

Ruby-crowned Kinglet

We may be quarantined but that doesn’t mean we have to miss the magic of migration. As I write, there’s a ruby-crowned kinglet singing in a maple across the street. We can bird, or learn birds, in our backyard or neighborhood. We can bird a new local patch and contribute what we see to science by logging our sightings into ebird.com. Over the last few years people in Pennsylvania have found some amazing birds in their own backyard. A Black-backed Oriole from Mexico, a Painted Bunting which overshot the Carolinas by more than a few states, and even a Bahama Woodstar. With migration, we never know exactly what we’re going to get. To me that’s part of the magic. That, and knowing that it’s time for them to come, carried hundreds or even thousands of miles by their wings and the wind.

Luke DeGroote is the avian research coordinator at Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s environmental research center. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.