by John Wible

The third Saturday in February marks World Pangolin Day, celebrating the scaly anteater that is sometimes called the pinecone mammal. Pangolins are covered with scales made of keratin, the same stuff in your fingernails and hair. Because some traditional medicines mistakenly impart curative powers to their scales, pangolins have become the most heavily illegally trafficked animal on the planet. Pangolins lack teeth and live exclusively on social insects, like ants and termites, which they catch with their very long sticky tongue. Today, there are eight species of pangolins, four in Asia and four in Africa. The fossil record reveals greater diversity and geographic distribution for these unusual creatures, including Europe and North America.

I study the evolutionary relationships of mammals, building family trees based on the anatomy of living and extinct species. In the 1800s and 1900s, pangolins were grouped with other mammals that are toothless or have very reduced teeth, such as anteaters, aardvarks, sloths, and armadillos, in the aptly named Edentata (think edentulous, or “toothless”). In the last 25 years, the study of DNA has revealed a totally different set of relationships for these edentate mammals. Aardvarks are in an African group with elephants, elephant shrews, tenrecs, and hyraxes; anteaters, sloths, and armadillos are in a South American group; and pangolins are most closely related to Carnivora (dogs, bears, cats, hyaenas, raccoon, etc.). It is hard to imagine that the gentle, toothless pangolins are close kin to the ferocious meat-eater lineage that includes lions, tigers, and saber-toothed cats.

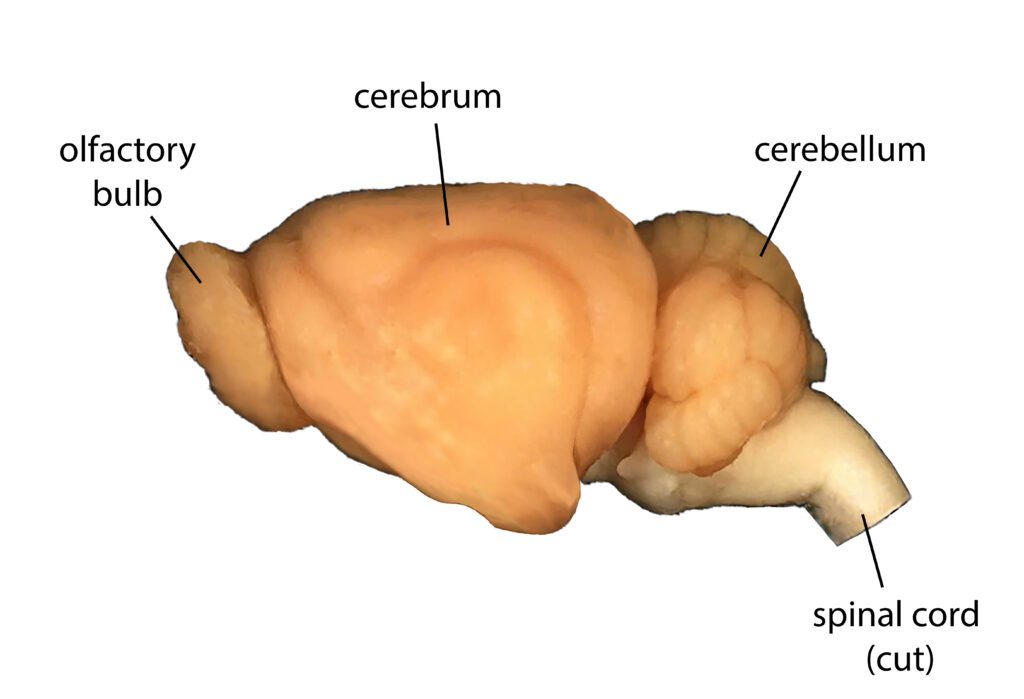

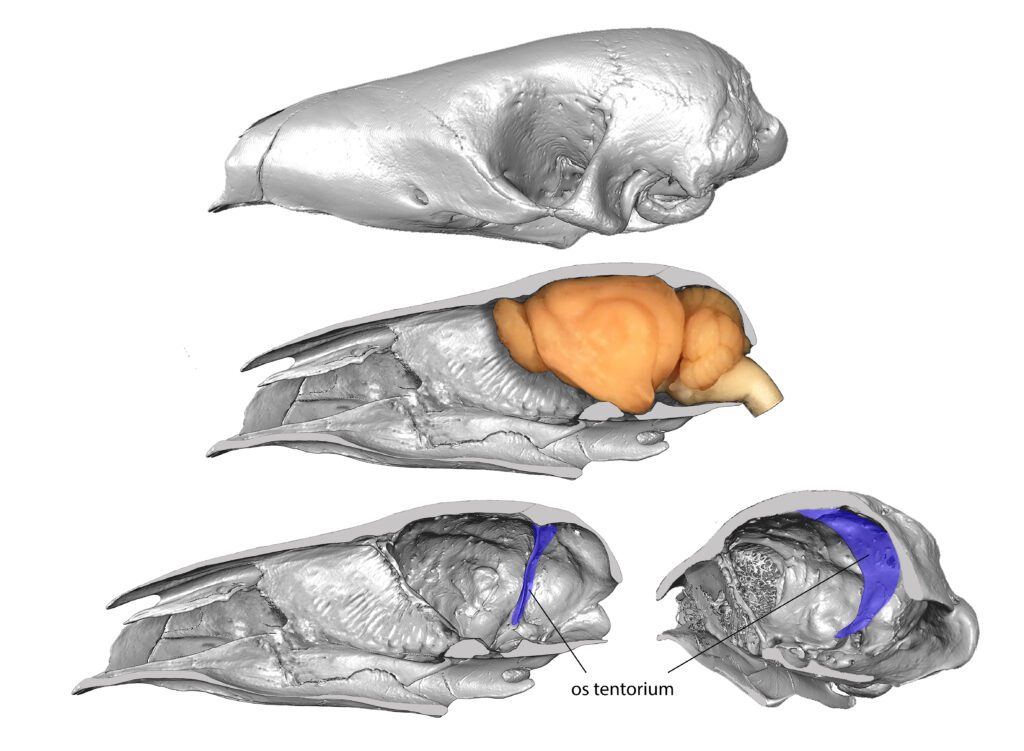

Although DNA supports relationships of pangolins and carnivorans, we are hard pressed to find anatomical features that link the two groups. One unusual feature shared by both and, therefore, hypothesized to be present in their common ancestor is the os tentorium or brain bone! A typical mammalian brain is composed of three parts delimited by deep grooves, termed sulci, the fore-, mid-, and hindbrain, which correspond respectively to the olfactory bulbs, cerebrum, and cerebellum.

The human brain is dominated by its greatly enlarged cerebrum with tiny olfactory bulbs; pangolins and carnivorans have a much better sense of smell with well-developed olfactory bulbs and relatively smaller cerebrum. The brain in mammals is encased in a fluid-filled space surrounded by layers of connective tissue and within the bony braincase of the skull. One of the connective tissue layers, the dura mater, has a fold called the tentorium cerebelli (meaning the tent of the cerebellum) that fits in the deep sulcus between the cerebrum and cerebellum. In pangolins and carnivorans, the connective tissue tentorium has a layer of bone in it, creating a partial bony separation between the cerebrum and cerebellum. In pangolins and carnivorans, the os tentorium is not a single bone, but is made up of contributions from three or four skull bones. There are other mammals that independently have evolved an os tentorium, including horses, but it is not as extensive as that in pangolins and carnivorans.

Okay, so we have a nice anatomical feature allying pangolins and carnivorans. However, we are left with one very large unanswered question. Why? If it is such a good thing to partially separate the cerebrum and cerebellum by bone, why don’t all mammals do it? The os tentorium is said to be “protective” of the brain, but protective how? Did a random mutation some 60 million years ago in the common ancestor of pangolins and carnivorans lead to the formation of the brain bone in the living forms? Is the brain bone somehow linked to another innovation that is strongly selected for? Is there some function to the brain bone that our brains cannot fathom? As an anatomist, I can study the structure and distribution of the brain bone in living and extinct mammals but to get at the “why” question may require a deep dive into molecular biology. Understanding the genetics behind the os tentorium may be the only path forward on cracking this mystery.

John Wible is Curator of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wible, JohnPublication date: February 16, 2023