by Mason Heberling

Though the supercontinent Pangea broke apart many millions of years ago, the Anthropocene is marked by a new kind of Pangea. The globalization of human activities has brought species from around the world into contact which otherwise would never interact. Though the seven continents as they are today may not be physically connected into a single landmass, they are perhaps more connected than they have ever been.

Some species are intentionally moved from one continent to another, such as the plants in gardens, while other introductions are accidental, mere unintentional passengers of humans increasingly global activities. Introduced species can fundamentally alter the landscape and are regarded as one of the top threats to native biodiversity.

Invasive species are those introduced species which are non-native and spread without human intervention. Many invasive species alter ecosystem functioning and change regional biodiversity. Invasive plant species have become a common part of our landscape. Some were brought over hundreds of years ago by European colonists. Others have arrived much more recently.

In Pennsylvania, the invasion of some plant species is obvious – that is, a unique species arrives, thrives, and become abundant. These invasive species have no record of being in the area and can spread rapidly, sometimes over the course of a human lifetime or shorter. Many invasive species are still actively spreading across the landscape. For instance, garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a well-known forest herb from Europe introduced to North America in the mid-1800s. After more than a century, the plant is now common across Pennsylvania’s forests. Another obvious example is giant knotweed (Reynoutria sachalinensis), a native to parts of East Asia, first recorded in western Pennsylvania in the 1920s, and since spread to line many of Pennsylvania’s rivers and streams. You can’t go far in the Pittsburgh region without seeing invasive knotweed.

Other species invasions are less obvious. These so called “cryptic invasions” are the introductions of very closely related species or subspecies which originated elsewhere.

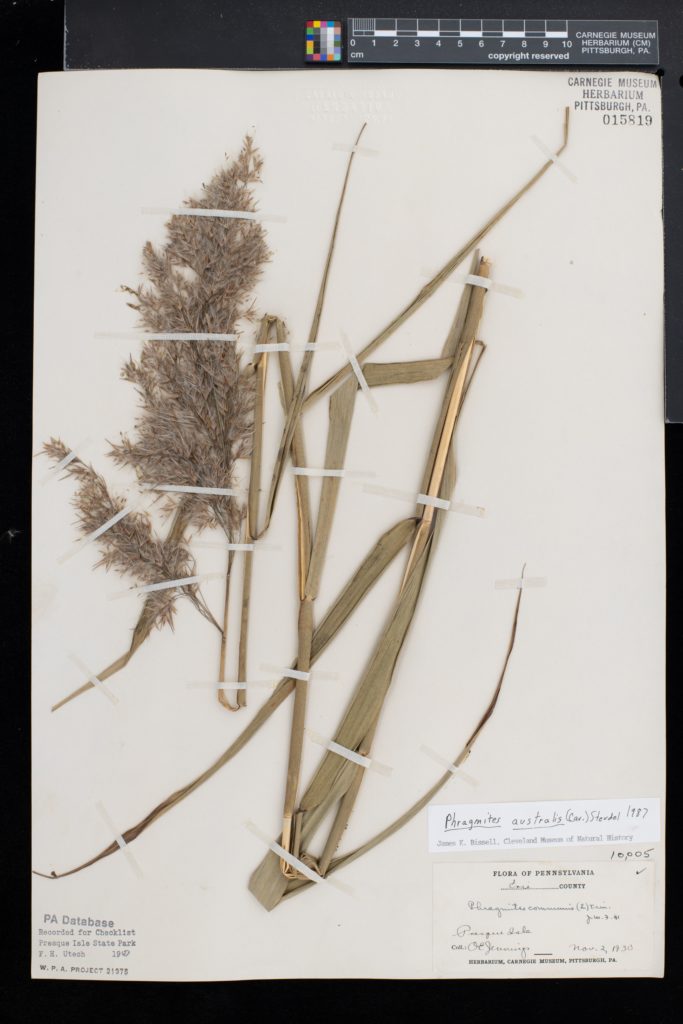

This specimen of common reed (Phragmites australis) tells the tale of a widespread cryptic invasion. The specimen was collected by Carnegie Museum botany curator Otto Jennings on November 2, 1930 along the shores of Lake Erie at Presque Isle, Pennsylvania. Common reed is a major problematic invasive species, crowding out native species in this unique habitat at Presque Isle. When this specimen was collected over 90 years ago, it was not nearly as abundant as it is now.

But is it non-native? Common reed, or often simply called Phragmites, has a very widespread distribution, found in wetlands and shores across all continents except Antarctica. It is even a common site along wet areas near highways. Common reed is among the most widely distributed plants in the world.

Reed is non-native to the United States…well, mostly. In the 1800s, botanists considered Phragmites to be a relatively uncommon plant. Evidence from fossils and paleoecological research show that the species has indeed been in North America for many thousands of years. However, it didn’t start to become abundant until the early 1900s and after. Some botanists suggested the sudden success of the species could be due to human disturbance. A pioneering herbarium-based study from 2002 published in PNAS by Dr. Kristin Saltonstall sequenced DNA from herbarium specimens collected before 1910 and recent collections to show that the spread of Phragmites in the United States was due to the introduction of a non-native strain of the species that originated from Europe.

Pretty cool, huh? And this finding was made possible with herbarium specimens.

So, is this particular specimen native or not? I don’t actually know, but with expert examination and genetic analysis, we could find out!

Find this specimen and 149 more in the Carnegie Museum herbarium here.

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. These scientists are in the midst of a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

The Circle of Life…and Invasion

Ask a Scientist: How do you find rare plants? [Video]

Collected on This Day in 1982: One specimen isn’t always enough!

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Heberling, MasonPublication date: November 12, 2021