Disclaimer: Our dinosaur paleontologist Matt Lamanna typically edits Lindsay Kastroll’s Mesozoic Monthly posts before they go live, but due to some much-needed holiday revelry he was late in getting to this one. As such, it’s being posted in January rather than in December as Lindsay had intended. Matt sends his apologies!

‘Tis the season for eating candy canes, singing Christmas carols, and kicking off a new year of Mesozoic Monthly! That’s right – one year ago, the first Mesozoic Monthly debuted in December 2019, spotlighting the ceratopsian dinosaur with a candy cane-shaped nasal horn, Einiosaurus. This December, we’ll move from candy canes to carols as we feature Vegavis iaai, the first Mesozoic bird known to have had a syrinx (the avian “voice box”)!

Birds evolved during the Mesozoic Era, the so-called “Age of Dinosaurs,” before non-avian dinosaurs became extinct. Last month, for the November edition of Mesozoic Monthly, we discussed what makes modern birds members of the group of theropod dinosaurs, but what I didn’t mention is that birds lived alongside non-avian dinosaurs! Birds evolved around 165 to 150 million years ago during the Jurassic Period, the second of three time periods in the Mesozoic. The Jurassic dinosaur Archaeopteryx represents a transitional stage between birds and non-avian dinosaurs: its fossils display obvious flight feathers like a bird, but it also has many non-avian dinosaur characteristics such as a toothy mouth, a long bony tail, and even a miniature version of a killing claw like that of Velociraptor.

Birds lived and evolved alongside their non-avian relatives for almost 100 million years, and by the end of the Cretaceous Period (the third and final time period of the Mesozoic), the distinct groups of birds that we recognize today were beginning to originate. Vegavis was an ancient relative of ducks and geese discovered on Vega Island, an island off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula (the part of Antarctica that juts northward towards South America). At that time, Antarctica was warmer than it is now and home to lush temperate forests.

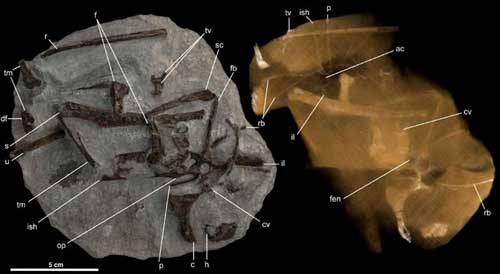

With many skeletal features suggesting that it was a diving bird that propelled itself with its feet, Vegavis was probably as well-adapted to life in the water as it was to life in the skies. While it’s certainly incredible that scientists are able to deduce this much information about its behavior from just its skeleton, the story gets better: one specimen of Vegavis includes a fossilized syrinx, the organ that birds use to produce sound! A syrinx’s shape is directly related to the sounds it can make, and the fossilized syrinx of Vegavis was a distinctively goose-like asymmetrical shape. So, this ancient bird may well have honked! If it did, it would have sounded much more like six geese-a-laying than, say, four calling birds, three French hens, two turtle doves, or a partridge in a pear tree.

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What kind of dinosaur is a megaraptorid?