New to this series? Need to catch up on your reading? Here are all the previous posts for the Bromacker Fossil Project: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI, Part VII, Part VIII, Part IX, Part X, Part XI, and Part XII.

The Bromacker quarry is a rare site in that it preserves exquisite, articulated fossils of a unique vertebrate fauna that lived in an atypical or rarely recorded Early Permian (~290 million years ago) setting. Early in our work at the Bromacker, we became aware that the fossil vertebrates we were finding were unknown or extremely rare in Europe but were closely related or identical to species commonly found in North America. Until then, most of the fossil vertebrates found in Europe were discovered in gray to black sediments deposited in ancient lake beds, whereas the fossils from the Bromacker quarry occurred in red beds representing a terrestrial setting. Paleontologists looking for fossils in Europe typically prospected the gray to black sediments where fossils were relatively plentiful rather than red beds, which were thought to represent arid environments not conducive to fossil preservation.

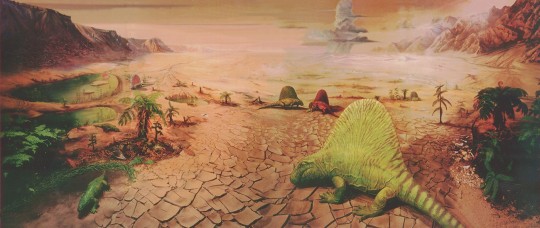

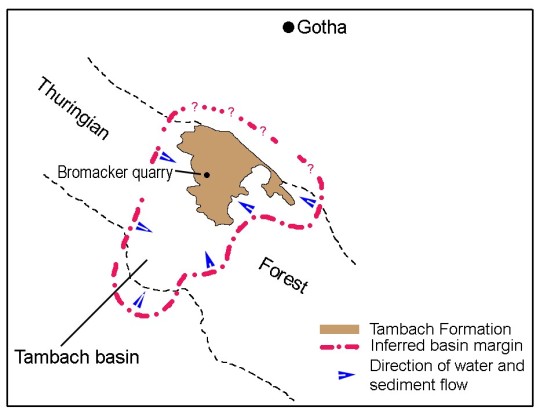

In a collaborative effort to help determine how the fossil deposit at the Bromacker quarry formed and why its vertebrate fauna is unique, Dave Berman invited his colleague David Eberth to join us for the 1998 field season. David is a geologist/vertebrate paleontologist who was then employed by the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Canada but is now retired. The sediments preserving the Bromacker fossils are part of a rock unit called the Tambach Formation and were deposited in the Tambach Basin. The results of David’s study, built in part upon investigations by other geologists and paleontologists, indicate that the Tambach Basin was situated within an ancient mountain range and isolated from river systems. At the time the fossils were deposited, the basin was internally drained, and as a result, when it rained, water would flow towards the basin center and form ephemeral ponds and lakes. Based on the geology, fossil plant assemblage, and geographic setting of the Tambach Basin, David concluded that the climate was possibly similar to the wet‑and‑dry tropical climate of modern North African savannas, Brazilian Campos, or the Venezuelan Llanos.

Most of the fossils discovered at the Bromacker quarry came from two massive units, the more fossiliferous of which is about 21 inches thick, that formed in separate major flooding events. David theorized that these deposits formed when heavy rain caused a sheet-flood of sediment‑laden water to sweep down the sides of the Tambach Basin and across the basin floor, killing any animals that couldn’t escape the flow. The sheet-flood transported the carcasses to the basin center where they were deposited, rapidly buried, and eventually fossilized. These deposits record a unique snapshot of vertebrate life in the Tambach Basin, because only animals inhabiting the basin would have been captured by the sheet-flood.

In contrast, most Early Permian fossil‑bearing deposits in North America formed on coastal or alluvial plains. Carcasses would’ve been transported to the deposition sites by rivers, some of which had a large geographic reach. These types of deposits can accumulate over a long period of time and have potential to mix together fossils from different environments.

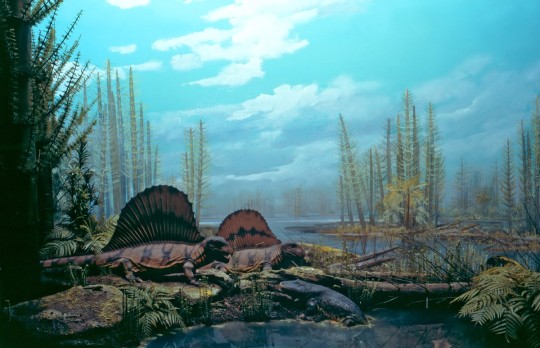

Besides having an atypical geographic setting, the makeup of the Bromacker vertebrate fauna differs from those known from other Early Permian sites. The Bromacker vertebrate fauna has a low diversity of terrestrial tetrapods, but more importantly, it lacks fishes and aquatic to semi‑aquatic constituents. This is probably due to the Tambach Basin’s isolation from regional river systems and because it experienced seasonal to sub‑seasonal drying, making it difficult for water-reliant vertebrates to become established. Based on numeric counts of individual specimens, we determined that the relatively large‑sized herbivores Diadectes, Orobates, and Martensius greatly outnumbered the synapsid apex predators Dimetrodon and Tambacarnifex. We think the rarity and low diversity of synapsid carnivores is probably due to the lack of an aquatic to semi‑aquatic component in the food chain.

In contrast, most Early Permian North American localities preserve a diverse, mixed aquatic‑terrestrial fauna that either lived in water or was closely associated with water and aquatic food chains. Herbivores were rare in terms of both diversity and numbers, whereas synapsid apex predators were diverse and numerous.

The Bromacker is the oldest known terrestrial vertebrate ecosystem in which herbivores greatly outnumber apex carnivores, and in that respect, it resembles terrestrial vertebrate ecosystems of today. A modern example is the African savanna in which large herds of herbivores such as zebra, wildebeest, and buffalo provide a food source for a much smaller number of carnivores including lions, cheetahs, and hyaenas. Indeed, we consider the Bromacker to represent an early stage in the development of the modern terrestrial vertebrate ecosystem and that these early stages were restricted to upland areas isolated from aquatic‑based food chains.

This summary concludes the Bromacker Fossil Project blog post series. I hope that you’ve enjoyed reading it. Cast replicas of many of the fossils described in this series are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition, so be sure to look for them on your next visit. I’m grateful to Dave Berman, Albert Kollar, Thomas Martens, and Stuart Sumida, who answered numerous questions and provided photographs, and to Patrick McShea and Matt Lamanna for their editing skills. Click here to read the paper by Eberth et al. 2000.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.