by Vuk Vuković

As a queer individual, I am in constant search of such representation in works of art and art institutions. However, Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) was the last place I expected to find it.

In the last decade, there has been a push for art institutions to acknowledge queer identities within their galleries. From Tate’s Queer Lives and Art to Art 50 Years After Stonewall at Columbus Museum of Art, art institutions are gradually responding to the public outcry for queer visibility. Although it seems like these initiatives are contemporary, queerness has always been around, especially in institutions centering their work around humans. However, due to stigma, their identities were hidden from the public eye, stored away in warehouses, or worse, placed in the galleries with no context.

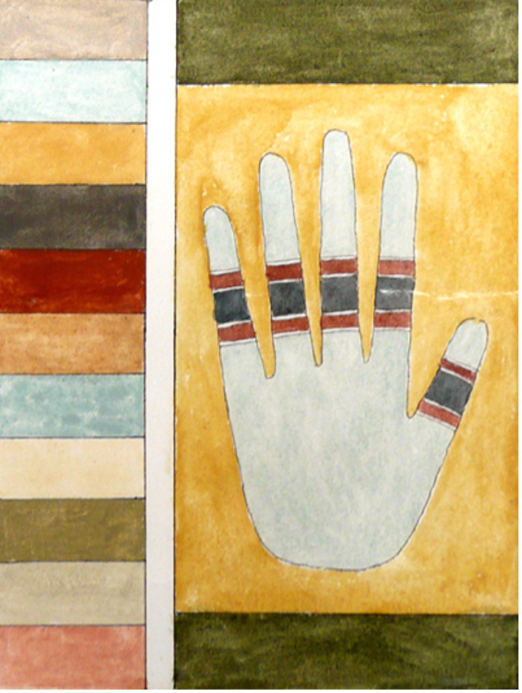

During my visit to CMNH’s Section of Anthropology at the “Annex” (the informal name for the Edward O’Neill Research Center), I was astounded by the richness of the collection that represents people in places ranging from the Latin American shores to the deserts of the Arab world. However, the work of art that caught my attention was a five-part panel by Thomas Haukaas, a contemporary Lakota artist. As a non-Lakota and non-Native person, I examine Lakota self-representation without claiming to participate in it myself. Instead, I focus on Lakota culture by citing sources created by members of the tribe and their allies. In Eye Candy (2008), the first panel (Figure 1) depicts a human hand situated next to the rainbow color palette. On the left side, eleven boxes are symmetrically distributed on the page and filled with different colors. Five out of eleven colors (red as a focal point) appear on the right side of the image that portrays a hand in a gesture that demands the viewer to stop. I regard the hand as a signal for viewers to pause and immerse themselves with the strikingly diverse pictorial elements, especially as other panels invite the viewer to look closely.

The second, third, and fifth panels (Figure 2) portray several patterned horses – an animal that became a symbol of freedom and representation of many Native American cultures.¹ I grew up admiring the relationship horses had with the land through the animated film Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron (2002). In the film, Spirit is set free from a U.S. army camp by a Native American man called Little Creek, who attempts to lead him back into the Lakota village. To a kid growing up in Montenegro, a small Mediterranean country in Europe, this was a film about the quest for freedom. As I am writing the blog post, I realize the visual elements Haukaas uses are easily interchangeable with the idea of running free as the horses in his work do. In Eye Candy, he uses the horses to express the diversity and inclusive practices of Lakota people. By applying subtle visual elements, Haukaas alludes to winyanktehca or winkte – “a term traditionally applied to male-bodied or biologically male individuals who did not identify as male or men.”² In contemporary Lakota culture, winkte is mostly used to refer to a homosexual man.³ While their status varied in historical records, most accounts treated the winkte as regular community members.⁴

The fourth panel (Figure 3) brings the work together as it combines all sections into one abstract form. I find the ambiguity of this panel to be an overarching connection because the queer community is diverse and fluid, but when it comes together, it is as striking as this panel. However, queer art is not always abstract as artists such as Andy Warhol and Keith Haring are explicit about queerness in their works.

As someone who has traveled across four continents and worked in different cultural settings, I am always on the lookout for queer representation, but my favorite encounters are when those representations find me.

Vuk Vuković is a PhD student in the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh and an intern in the Section of Anthropology and Archaeology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees and volunteers are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

References

[1]Richard Koepke, Harnessing the Force: A Manual for Weary Seekers (Bloomington: AuthorHouse, 2011), 11.

[2] Robert Allen Warrior, The World of Indigenous North America (New York: Routledge, 2015), 1,442.

[3] Beatrice Medicine, “Directions in Gender Research in American Indian Societies: Two Spirits and Other Categories,” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 3 (1), (2002): 4, https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1024.

[4] Sabine Lang, Men as Women, Women as Men: Changing Gender in Native American Cultures (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 118.

Related Content

Archaeological Adventures in Egypt

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Vuković, VukPublication date: May 18, 2021