For many people, the new year represents an opportunity to make a fresh start, consider self-improvement, or turn over a new leaf. As in all fields of human endeavor, insects are way ahead of us and have already developed the ultimate technology for personal reinvention: metamorphosis.

Among entomologists, “metamorphosis” refers to the process by which a tiny hatchling insect becomes a fully functioning adult. This process can take place in two ways. Incomplete metamorphosis is the process by which an insect molts through a series of increasingly large, adult-like stages (“instars”) before completing the final molt into an adult. Insects that develop this way include grasshoppers, stink bugs, dragonflies, termites, and mantises.

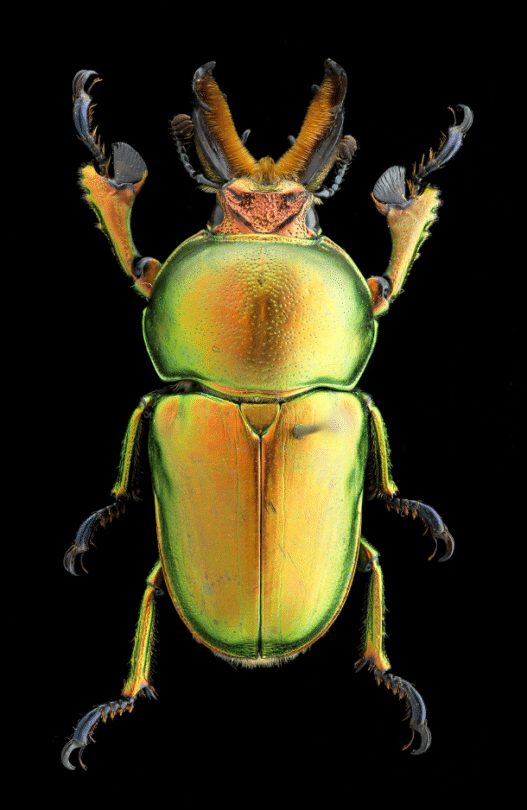

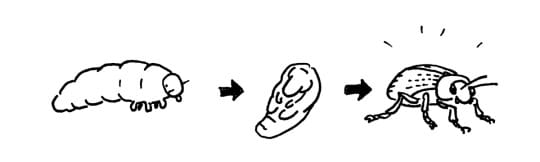

Complete metamorphosis, on the other hand, involves a (typically) worm-like larva which undergoes a quiescent, or inactive, pupal stage before reaching adulthood. Insects that undergo complete metamorphosis include beetles, ants, bees, wasps, lacewings and antlions, flies, and moths. These orders are often described as “holometabolous,” which simply means that their development includes pupation.

The process of pupation is fascinating and mysterious: essentially, the caterpillar zips itself up into a sleeping bag made of its own skin, turns to soup, and comes out a butterfly. How?

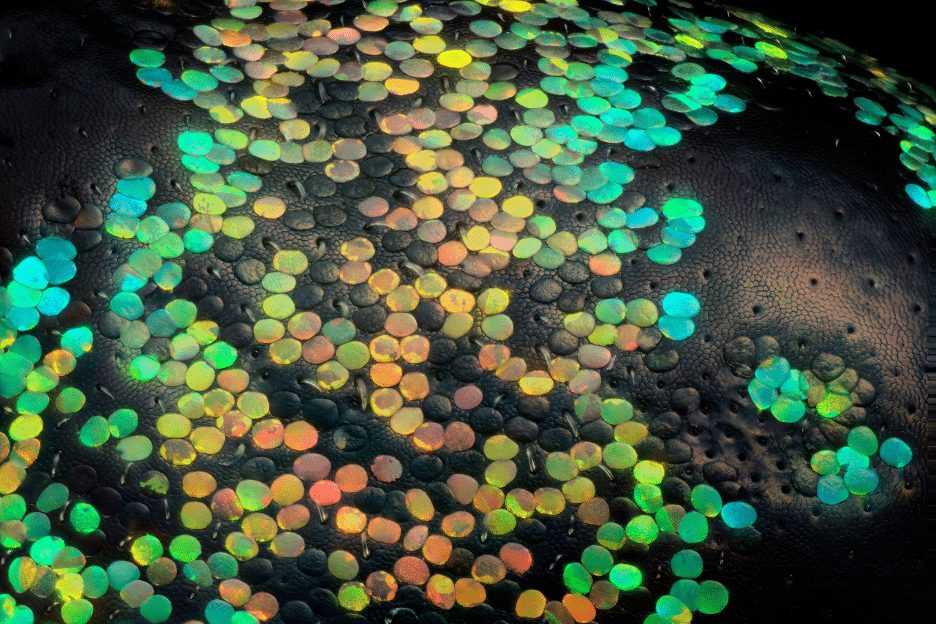

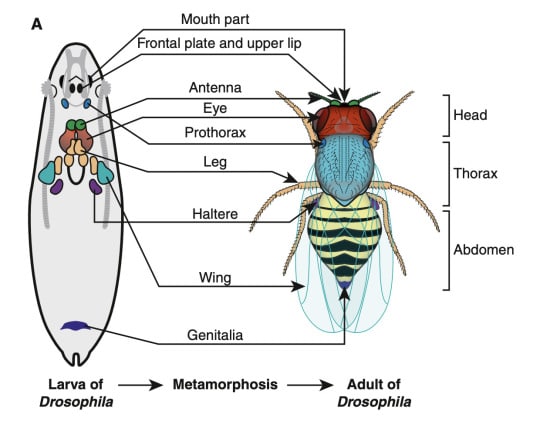

In fact, insect pupation remained a scientific mystery for many years, largely because of the difficulty in observing the pupation process without destroying or interfering with development. However, interfering with development turned out to be the key to understanding this process: early investigators (e.g. Jan Swammerdam, the 17th century microscopist) discovered that structures corresponding to the approximate positions of future wings could be dissected from within late stage, prepupal larvae. Several centuries later, the ability to induce fluorescence in selected cell lines allowed researchers to observe the activity of these future wings, legs, and antennae throughout larval development. This research led to the identification of what are now known as “imaginal discs.”

Here’s how it works: secret little collections of cells are formed during embryogenesis, and rest dormant inside the larva as it grows. The larva and its essential larval structures (usually the digestive system) grow larger, but the dormant cells do very little. These cells are known as imaginal cells and their aggregate structures are called imaginal discs (The term refers not to imagination, but to the imago, a synonym for the insect’s adult stage). The cells within these imaginal discs are largely dormant until a special cue— temperature, day length, growth, or otherwise— triggers the hormones that kickstart pupation. The larva forms a tough outer casing from its outermost exoskeleton or uses silk glands to create a protective nest (e.g. a cocoon).

As pupation begins and the larval body breaks down into fluid, the imaginal discs begin to undergo rapid development, telescoping outward to form the longer legs, wings, antennae, mouthparts, and other complex adult body structures. The only remnants of the larva that stay functional are the tracheae, hollow tubes which allow it to breathe.

Once the adult structures are fully formed, they will remain soft in order to fit inside the now too-small pupa. The pupal case splits open, and the newly emerged adult insect forces air and fluid into its new wings to unfurl them fully before they harden.

Forming a hard outer casing and liquefying your existing body may not sound like an inspirational concept for the new year, but perhaps it should. The lesson of the butterfly is that the developmental foundations of the beautiful, functional adult were inside the awkward, squirmy larva all along. The imaginal cells were always there, just waiting to be awakened.

For more discussion of insect pupation and tips on using caterpillars to get kids into science, see this previous IZ blog post by Dr. Jim Fetzner, “Kids and Caterpillars: Fostering a Child’s Interest in Nature by Rearing Lepidoptera (Moth and Butterfly) Larvae.”

Ainsley Seago is Associate Curator of Invertebrate Zoology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

O-Do-Nates or O-Don’t-Nates: Dragonflies and Damselflies in the Section of IZ