by Suzanne Mills and Albert Kollar

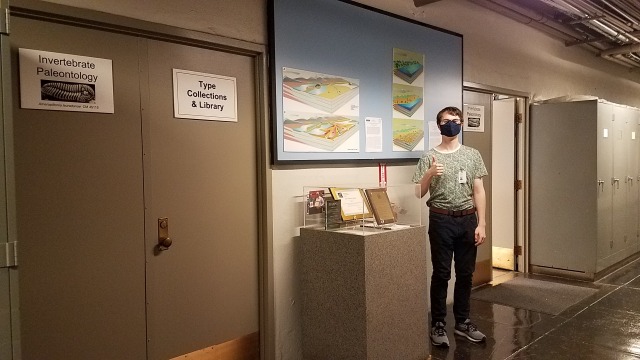

Gray metal storage cabinets march in rows across the concrete floor. The collection space has no windows and there is a constant hissing sound from the overhead air ducts. No matter, the staff is looking for clues of the geologic and paleontological past, or History of the Earth, through the vast collection of fossil invertebrates. The staff and volunteers of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology (IP) are tasked to reorganize, preserve, and curate fossils through the leadership of the Collection Manager Albert Kollar.

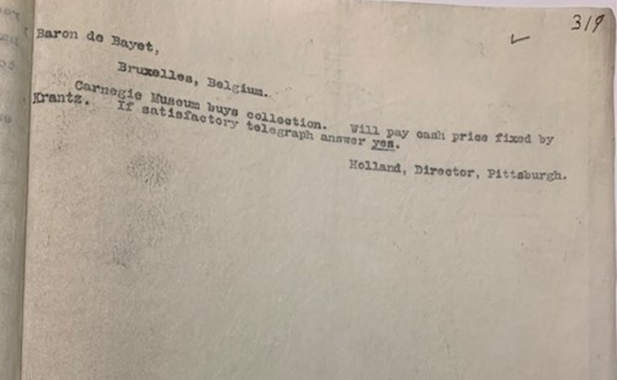

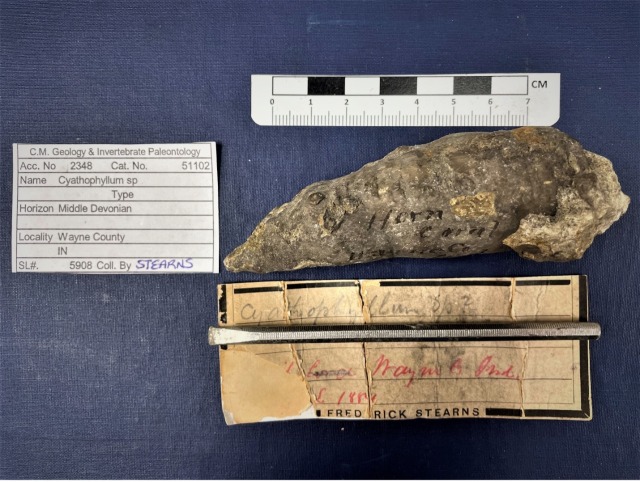

On any given workday, you’ll find us hefting drawers full of fossil-bearing rocks and playing specimen-box Tetris to make fossils fit in the available cabinet space. We examine century-old inventory books, search out (usually Google) maps to find absconded valuables (historical fossil sites), and decipher written scripts in unfamiliar French and German for valuable geologic data.

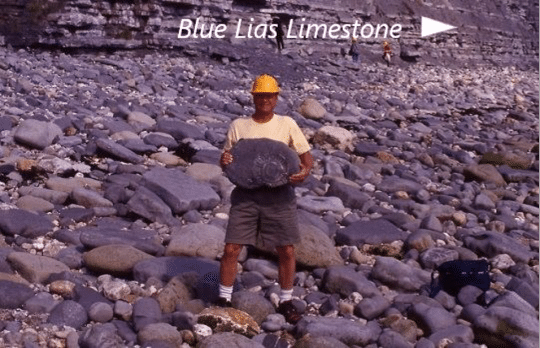

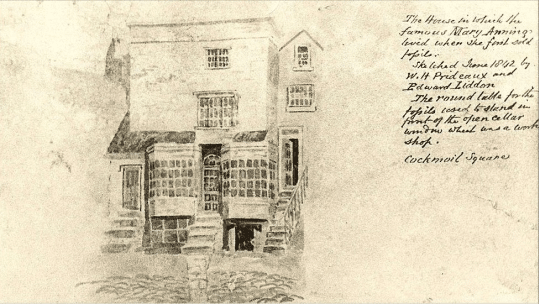

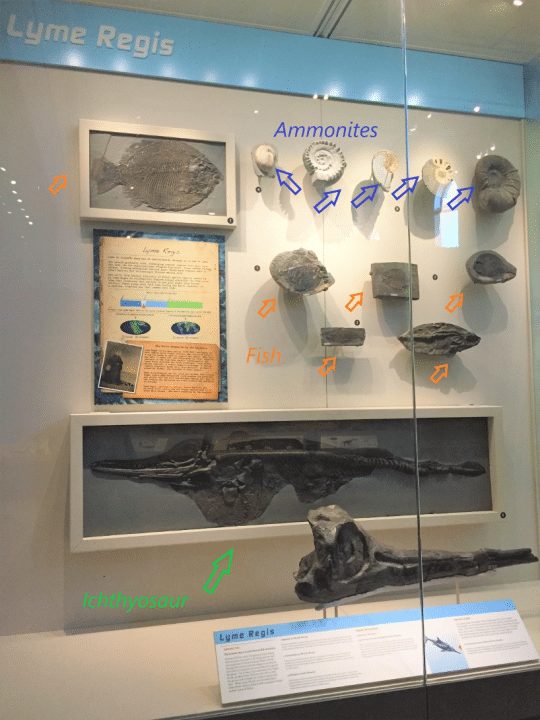

Long-term volunteers in IP include Rich Fedosick, a researcher assisting in the project to document the Carnegie building stones; John Harper, an expert on fossil snails taxonomy, Roman Kyshakevych, who is deciphering the famous Coppi collection from Italy; Tamra Schiappa, a paleontologist at Slippery Rock University who is updating fossil cephalopod identifications; and Vicky Sowinski, who performs collection support. Student researchers include collection assistant and graphic artist Kay Hughes, a 2021 Mount Holyoke College graduate who coauthored four peer-reviewed scientific publications produced by IP; and collection assistant Will Vincentt, who researched two Bayet collections, the Hunsruck Slate of Germany and Lyme Regis of England. Tara Pallas-Sheetz, a part-time assistant, has worked on various projects over the years.

Hear from some of our newest staff and summer volunteers in their own words below.

Name: Lizzie Begley

About me: B.A. Anthropology Penn State 2021; masters candidate in Museum Studies and Non-profit Management certification in progress at Johns Hopkins University

Why IP: Working “behind the scenes” in IP has helped me develop a better sense of what it looks like to work in a museum such as the Carnegie. As an aspiring museum professional, experience behind gallery floors is invaluable as I work to find my place in the field. For this experience I couldn’t be more grateful and, honestly, couldn’t be having more fun!

Name: Katie Golden

About me: B.S. Biology, Juniata College 2023 (expected)

Why IP: When I was in preschool, I told people I wanted to be a paleontologist when I grew up. Here in IP, I like exploring a part of the museum that most people don’t get to see. I particularly enjoy puzzle-piecing together fossils that need repair. The intricate ammonites, trilobites, and insects preserved in amber are especially beautiful. My favorite fossil organism is Anomalocaris.

Name: Tori Gouza

About me: B.A. History and Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh 2023 (expected)

Why IP: I love working in IP. It is so exciting to be able to interact with others in the section and to learn what projects they are currently working on. Albert Kollar has encouraged not only discussion but also collaboration. It is great to converse with others who are passionate about their work.

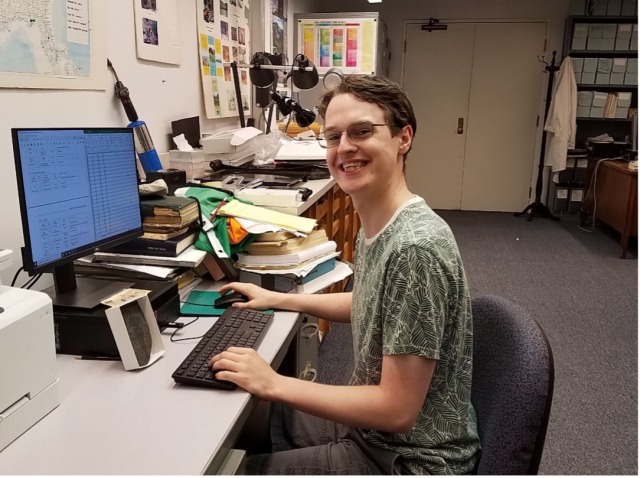

Name: Kevin Love

About me: IP Collection Assistant; B.S. Geology and Ecology & Evolution summa cum laude, University of Pittsburgh 2021

Why IP: I like solving puzzles at work. I find invertebrate fossils aesthetically appealing, but the main reason I like this job is that I get to understand little enigmas from Earth’s past. I like solving historical questions and compiling more information about fossils in the collection.

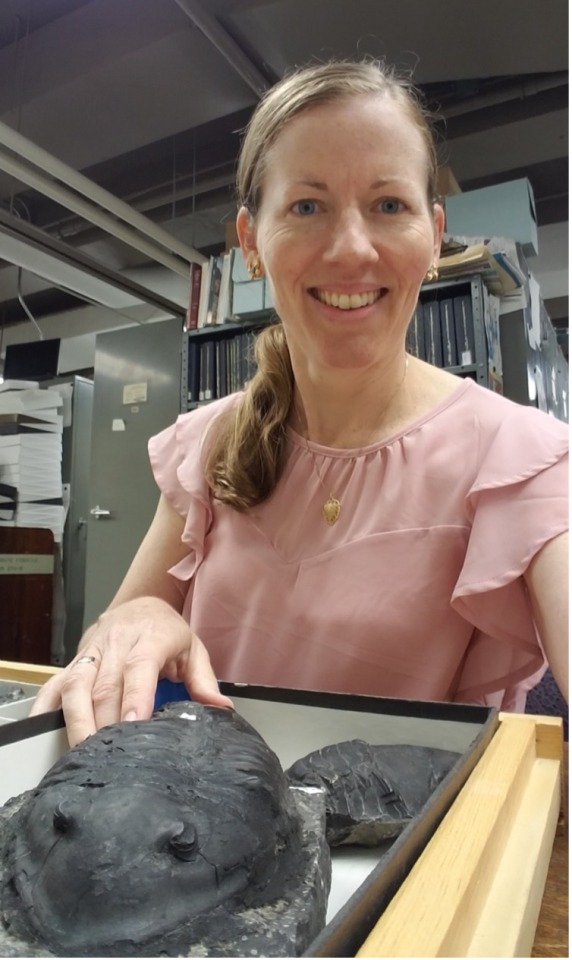

Name: Suzanne Mills

About me: IP Collection Assistant, Professional Geologist, mom

Why IP: Every day is different when you work with a collection of 800,000 specimens. I may come across a 100-million-year-old ammonite sparkling with crystals inside, or a drawer full of trilobites acquired by the museum in 1903, when Andrew Carnegie was alive. I love that my work requires me to learn more about fossils which are beautiful, historical, and scientifically significant.

Name: Ellis Peet

About me: B.S. Environmental Geoscience with Geology concentration, Slippery Rock University 2021

Why IP: The management and staff of IP are smart, kind, personable, and they take paleontology seriously. I also like the environment at IP because it smells like a library and limestone dust, which reminds me of the geology department at Slippery Rock.

Name: Joann Wilson

About me: Interpreter for the Department of Education, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Why IP: Fossils inspire awe. I enjoy unravelling the stories behind the individuals that discovered, studied and collected these breathtaking specimens.

Suzanne Mills is a Collection Assistant and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Mills, Suzanne; Kollar, AlbertPublication date: October 1, 2021