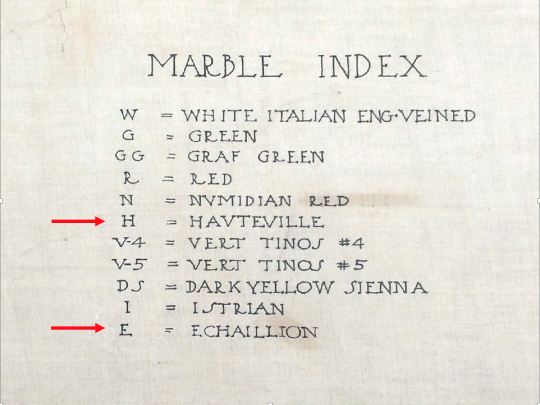

Figure 1.

When museum patrons enter Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Benedum Hall of Geology, they encounter a one-ton block of coarse sandstone with a series of bilateral footprints encased on the rock’s surface. Most visitors don’t know what type of creature made these footprints (Fig. 1) or realize that this fossil trackway represents one of the great fossil discoveries in the history of western Pennsylvania paleontology.

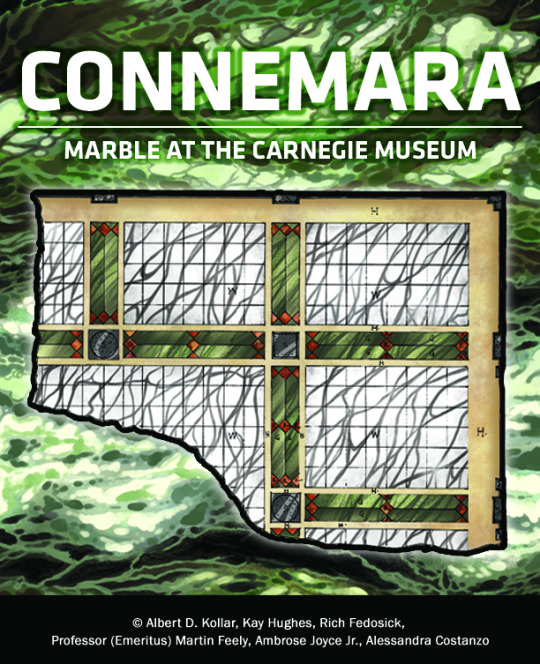

Figure 2. Illustration by Kay Hughes.

Last month, the cover of Pennsylvania Geology (Fig. 2) helped address both deficiencies. The magazine bears a colorful illustration by Kay Hughes of a 315 million-year-old scene: a large six-legged arthropod emerging from the water and dragging its tail onto a sand bar among fallen Lepidodendron logs. The intruder is a Giant Eurypterid, a creature known to science as Palmichnium kosinskiorum, and a member of an extinct family of arthropods informally called “sea scorpions” that are distant biological cousins.

Within the journal is a fuller explanation for the artistic interpretation of the creature behind the Benedum Hall trackway, an article I co-wrote with Kay Hughes and John Harper titled, Reflections on Palmichnium kosinskiorum-The Footprints of Pennsylvania’s Elusive Elk County Monster.

Fortuitous Discovery

Figure 3. Photograph of Elk County in situ trackway looking southward (Brezinski and Kollar 2016).

Figure 4. Trackway closeup showing tail drag on display in Benedum Hall of Geology (Brezinski and Kollar 2016)

Seventy-two years ago, in an Elk County section of the Allegheny National Forest, James Kosinski, a preparator in the Education Department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and his brother Michael were hunting deer in heavily wooded terrain. When Michael stumbled upon a large sandstone boulder bearing a pattern of unusual impressions, he informed James, who (Fig. 3) immediately recognized the impressions as the fossil tracks of an unknown animal (Fig. 4).

Later, when James described the discovery to Carnegie Museum’s Dr. E. Rudy Eller, Curator of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, and Dr. J. Leroy Kay, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology, plans were made to remove a section of the boulder containing the best-preserved section of the trackway and transport the heavy block to the museum.

Exhibit History

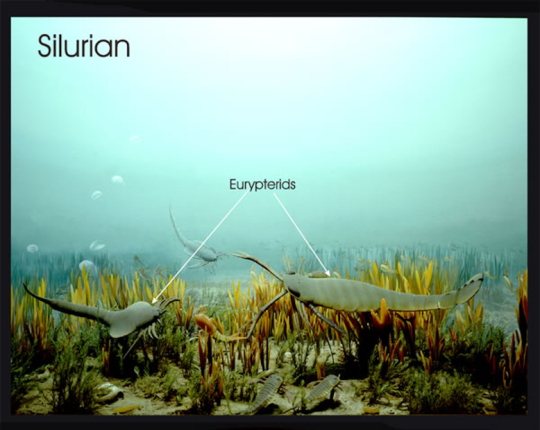

Figure 5. Former Paleozoic Hall Silurian Period Marine Diorama with Eurypterids.

Upon arrival at the museum in 1948, the sandstone block was prepared for exhibition and placed near the museum’s Coal Forest exhibit in 1949. In 1965, the trackway was incorporated as a floor centerpiece in the newly open Paleozoic Hall which featured dioramas of characteristic life forms of that Era’s time periods (Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian) along with representative fossils from the museum collection. (Fig. 5) In 1998, when Paleozoic Hall was dismantled, the trackway was placed temporarily in the Invertebrate Paleontology lab. The trackway returned to public view in 2007 as part of Bizarre Beasts, a temporary exhibition in the R. P. Simmons Family Gallery about unusual life forms. When Bizarre Beasts closed, I worked with James Senior, Chair of the museum’s Exhibit Department, to place the trackway in the Benedum Hall of Geology entrance as an introduction to great fossil discoveries from western Pennsylvania.

The Research – Locality Data Supports Recent Theory

The fossil trackway was initially identified by Dr. Kay as a hopping reptile inhabiting a Pennsylvanian coal forest 300 million years ago. Although Dr. Eller, citing his own research, suggested the track was formed by a crawling eurypterid, it would take 35 more years for the fossil trackway to be studied by expert arthropod paleontologists from Europe.

The eventual designation of Palmichnium kosinskiorum as a holotype specimen (CM 34388), a category of first order scientific importance, dates to the fossil’s description as a eurypterid trackway in a 1983 research paper by Dr. Derek E. G., Briggs and Dr. W. D. J. Rolfe, titled, A giant arthropod trackway from the Lower Mississippian of Pennsylvania (Journal of Paleontology, 57, 377 – 390). In paleontology, when a non-scientist such as Michael Kosinski discovers a fossil of importance, paleontologists, in this case Derek Briggs and Ian Rolfe, name the new fossil species after the founder, hence P. kosinskiorum.

For years, paleontologists in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology assumed the scientific conclusions of Briggs and Rolfe (1983) about the eurypterid trackway were beyond dispute. This situation changed in 2009, when Yale University Professor Adolph Seilacher, a world-renowned expert on fossil trackways visited the museum. While Briggs and Rolfe concluded the trackway formed in a marine sandstone, Seilacher explained to me that the trackway was likely formed in an eolian or wind-blown sand environment. He also recommended that someone investigate the rocks at the fossil location in Elk County to substantiate his hypothesis.

Figure 6. D.K. Brezinski at trackway.

Later that year, when I accompanied David K. Brezinski, Associate Curator Adjunct, Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, to re-locate and re-examine the sandstone boulder with the remaining tracks, we discovered the original geologic and deposition conclusion by Briggs and Rolfe (1983) was incorrect (Fig. 6). In 2011, we reported these new findings at the Northeastern Sectional Meeting of the Geological Society of America in Pittsburgh. After the meeting, we continued our research and eventually published our conclusion that the geologic age of the trackway was Early Pennsylvanian age and the embedded footprints represented a fluvial sand bar environment of deposition.(Reevaluation of the Age and Provenance of the Giant Palmichnium Kosinskiorum Eurypterid Trackway, from Elk County, Pennsylvania, Brezinski and Kollar (2016), Annals of Carnegie Museum 84, 39 – 45,)

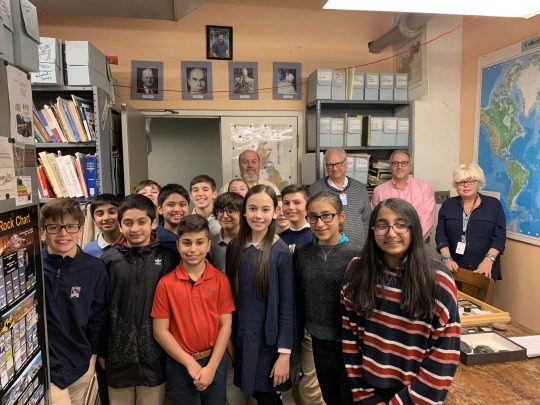

School Groups and Museum Interpreters

Based upon repeated anecdotal reports from the Interpreters who guide tour groups through the museum’s exhibit halls, the eurypterid trackway is one of the most celebrated education stops for elementary school students. According to Interpreter Patty Dineen, the appealing factors of the trackway include the size and possible scariness of the creature who made the tracks, the fact the track-maker lived long before the dinosaurs, the fossil’s local origin, and the sheer amount for information that can be gathered from the ancient preserved tracks.

Figure 7. Interpreter field trip.

As part of an effort to better inform school groups about the eurypterid trackway, in 2017 Patty Dineen and Joann Wilson, co-coordinators and instructors for the museum’s Natural History Interpreters, arranged for six Interpreters to participate in a PAlS geology fall field trip to the fossil site in Elk County. (Fig. 7) An important by-product of field excursion was the creation of an instructional video that explains how museum scientists conduct research.

“Treasures of the Carnegie” Planning for a better Trackway Experience

Now that an illustration exists (Fig. 1) of the eurypterid that shaped the trackway walking out of the 315 million-year-old Olean River onto a sand bar, it might be time to consider how to best devise an improved visual and virtual tour experience for the Carnegie patrons and school groups.

Albert D. Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.