Albert Kollar, Collections Manager for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, is on a mission to re-examine the Bayet Collection, a collection of 130,000 invertebrate and vertebrate fossils brought to the Carnegie more than 100 years ago. Albert is re-examining the invertebrate portion of the Bayet (pronounced “Bye-aye”), which as it turns out, is 99.9% of the collection.

The story starts with a last-minute trip that began on July 8, 1903 by Carnegie Director William Holland, who had received word of a world-class fossil collection that had been put up for sale in Europe by the Baron de Bayet, secretary to the cabinet of Leopold II of Belgium. Holland immediately booked passage to Europe on the steamer “New York” to complete the deal. At stake were 130,000 invertebrates, combined with a small number of vertebrate fossils (several on display in the Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition), sought by museums throughout Europe, Great Britain and the United States. This collection became the largest addition to the department of paleontology at the Carnegie Institute, since the discovery of the dinosaur Diplodocus carnegii, at Sheep Creek, Wyoming in 1899.

Mr. Carnegie personally wrote a check for $25,000 for the project, a sum so large it exceeded the entire 1903 budget for all art and natural history acquisitions combined. Eventually, Mr. Holland negotiated a price of just under $21,000 with the Baron de Bayet for the entire collection. Another $2,300 was spent to pack, insure and transport everything back to Pittsburgh. Twenty men and women worked for three weeks to meticulously wrap each fossil in cotton, batting, or straw and by September 1903, two hundred and fifty-nine crates arrived safely in Pittsburgh. Storage of the crates was an issue, since the Carnegie Museum building would not be completed until 1907; so Mr. Holland rented space in a warehouse on 3rd Street in Pittsburgh for storage of 210 of the 259 crates.

This decision, however, almost destroyed the collection when a fire broke out on the upper floors of the 3rd Street warehouse. On December 30, 1903, Mr. Holland wrote, “Yesterday brought with it a fire in which it appeared as if the Bayet collection, the acquisition of which we had so prided ourselves, was destined to go up in smoke.” Fortunately, the Pittsburgh Fire Department contained the fire to the upper floors and the Bayet collection, stored on the lower floor, and meticulously wrapped and crated, survived with minimal damage. The crates returned to the Carnegie Institute to dry out.

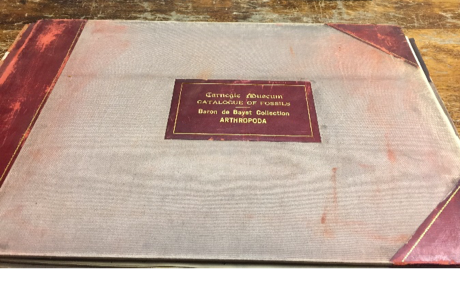

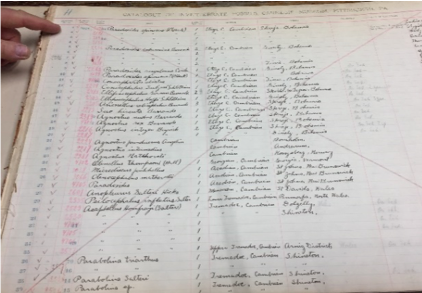

In early 1904, William Holland hired Dr. Percy Raymond, a graduate of Yale University, to be the first curator of Invertebrate Paleontology. His primary directive was to catalog and organize the Invertebrate portion of the Bayet collection. Today, over 100 years later, Albert Kollar with the help of Pitt Geology student E. Kevin Love, is undertaking a multi-year project to translate Percy Raymond’s beautifully hand-written catalogs and to migrate all 130,000 specimens into a new database.

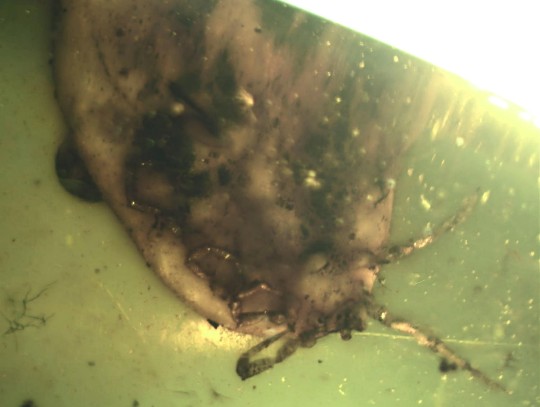

Pictured below is (BH1) the very first Bayet specimen cataloged by Percy Raymond. BH1 is an exquisite 510-million-year-old, CM 1828 Paradoxides spinosus, a 17.17 cm or 7” long trilobite from Skreje, Bohemia – or the Czech Republic of today.

Albert’s goal in revisiting the Bayet collection is to better understand the great history of the how, why and where of fossils collected in the late 19th century, especially in Europe the birthplace of paleontology and geology. “This project will give us insight into why certain Bayet fossils were recovered from classic European fossil localities, many of which are designated stratotype (significant geologic time reference) regions. These fossils and localities have been used to document the validity of evolution, extinction, and the Geologic Time Scale over the last 100 years. With an improved database, we hope to better appreciate the scientific value of the entire collection and create new statistical measures for future research and education.”

When asked if he expected any surprises as we go forward, Albert smiled, “Not until all the data has been analyzed will we have an opportunity to review the collection’s full scientific worth.”

Check back in a few months, Bayet’s invertebrates may have a few secrets yet to share.

Many thanks to Carnegie Museum Library Manager, Xianghua Sun for help researching this post.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.