By Kaylin Martin

Fueled by caffeine and the promise of a sighting of the elusive and threatened green salamander, I made my way to the assigned meeting point in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. I was told we would be meeting a contact that could lead us to his secret location wherein there was prime habitat for green salamanders. Slowly, a muddy truck approached us and motioned for us to follow him. Thirty minutes of unpaved, unmarked, pothole riddled roads later I was standing in front of a hillside with rough terrain.

I knew I was in for an intense hike. Green salamanders are found in rock crevices in outcroppings or on the sides of cliffs. Unlike most salamanders that can be found abundantly under damp logs or rocks, green salamanders are extreme habitat specialists. Because of their habitat requirements, these salamanders are considered Near Threatened by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The green salamander is listed as Endangered in Indiana, Ohio, Maryland, and Mississippi, as Threatened in Pennsylvania, and as Protected in Georgia. Some herpetologists argue that they should be nationally classified as Endangered, given that population sizes are decreasing due to habitat loss, drought and road development.

Armed with flashlights, our group of enthusiastic herpetologists made our way toward outcrops of rock along the hillside. We pointed our flashlights into every small crevice big enough to fit a salamander, hoping to see two large round eyes staring back at us. Within the first hour, we found a handful of common slimy salamanders, Plethodon glutinosus. Distinguished by their black color with silver or gold spots running along their backs, slimy salamanders are most known for the sticky substance they exude when threatened. Mostly found under logs or stones, the slimy salamander is also known to utilize its climbing abilities to crawl into crevices of shale banks, the same habitat that green salamanders favor.

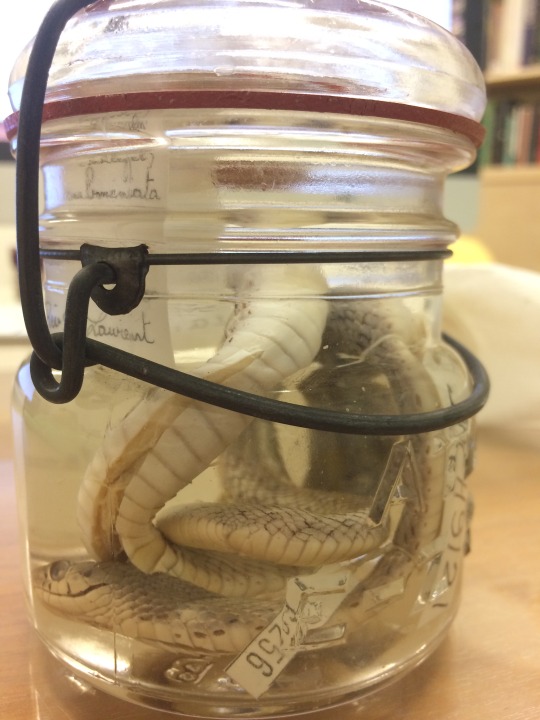

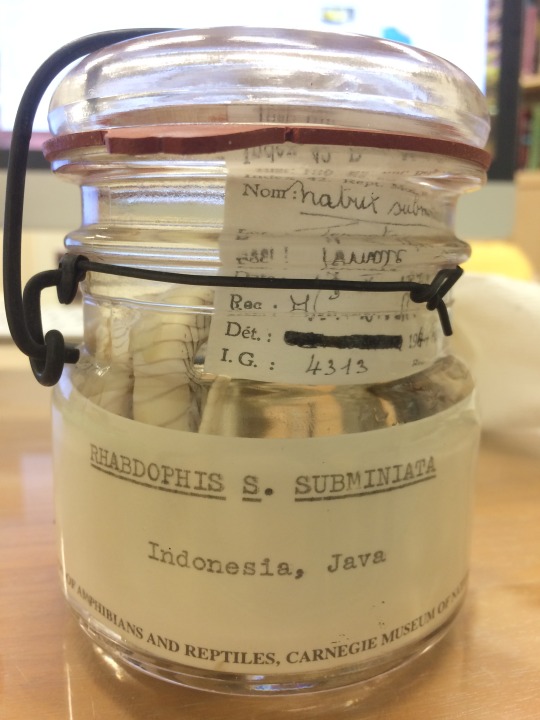

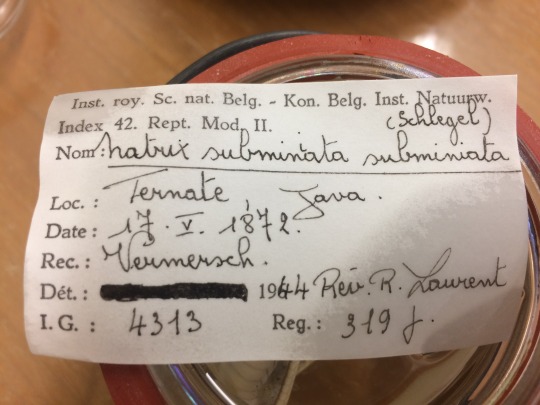

As I was photographing an eastern red-backed salamander, Plethodon cinereus, I heard a yelp of excitement, “A green! A GREEN!” A few agonizing minutes of scrambling through brambles and rocky terrain to get to my colleague ensued. As I approached, I was filled with excitement. Being the Curatorial Assistant of Amphibians and Reptiles allows me to catalogue specimens from all over the world, collected by renowned scientists in my field. This position gives me a platform to tell the public about why amphibians and reptiles are so important to our ecosystem. The thrill of seeing a Near Threatened salamander in its natural habitat reaffirmed my love for my career and the honor I feel in being an ambassador for amphibians and reptiles. Nothing beats the opportunity to photograph the species camouflaged into the moss around it, or the few minutes where you promise yourself and the species in front of you that your life’s goal is to promote environmental awareness of Pennsylvania herpetofauna (reptiles and amphibians), and the hope that maybe the green salamander will thrive in Pennsylvania in the age of the Anthropocene.

What can you do? Check out the Pennsylvania Amphibians and Reptiles Survey at https://paherpsurvey.org/.If you find an amphibian or reptile, take a photo and send it to the PA Herp Survey to help document the biodiversity and status of Pennsylvania herpetofauna.

Kaylin Martin, M.Sc, is the curatorial assistant in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.