by Rohan Mandayam

As an aspiring field biologist, I long harbored several dreams that I hoped would come to fruition sometime in my post-undergraduate career. Among those goals was conducting research on frogs, which have fascinated me since a young age. I also dreamt of working in the field and studying tropical ecosystems, as the biodiversity found in the tropics is rivaled by no other region on Earth. Imagine my delight when I discovered that I would be spending two months in Borneo as a research assistant to Dr. Jennifer Sheridan, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Curator of Amphibians and Reptiles, studying frogs in tropical rainforest streams. June couldn’t arrive fast enough.

The rainforests of Borneo are among the oldest in the world, known for their staggering concentration of biodiversity across species groups. With dipterocarp trees stretching over 80 meters into the canopy, orangutans rustling through the foliage, and crystal-clear streams rushing through the understory, my “office” for the summer was quite a sight to behold. Inhabiting those pristine streams and the forests surrounding them are Borneo’s nearly 200 species of frogs. In a region home to hornbills, clouded leopards, and one of the world’s most recognizable great apes, the choice to study small amphibians may not seem intuitive. However, frogs are an excellent study system for answering a wide breadth of biological questions, partly due to their high sensitivity to fluctuations in environmental conditions. Due to that sensitivity, studying frogs provides scientists with insights into the impacts of human-caused climate change and other anthropogenic factors on global ecosystems. Furthermore, amphibians remain the vertebrate group most threatened with extinction, and understanding amphibian ecology is critical to ensuring the conservation of those species into the future.

Our research this summer had two main focal areas. The first involved surveying frog populations in streams in different land-use types: primary forest, secondary forest, and agricultural land. We conducted visual encounter surveys of streams in each of those land-use types, noting each individual frog we saw and capturing it if possible. Carefully capturing the individuals allowed us to mark the frog (to establish whether we were recapturing individuals in subsequent surveys) and determine the sex, snout-vent length, and mass before releasing them. Repeated surveys on each of our study streams provided us with insight into the species richness and abundance of each frog community and enabled us to compare potential differences in our study variables across land-use types.

The surveys presented several enjoyable learning curves. We identified all frog species we found using their scientific names, so I had to learn taxonomy for the first time, butchering many Latin pronunciations along the way. I also learned to use specific features of an individual frog, including toe pads, hand and foot webbing, and parotid gland shape, to distinguish between easily confused species. Through experience, I began to recognize where certain species preferred to sit or perch, which ranged from the rocky shoreline to branches several meters above the water. And, through many ill-fated attempts to capture the more jumpy members of the anuran (frog) community, I realized which frogs merited a more slow and cautious approach before diving in to grab them.

Our second research focus for this summer was to record as many frog calls as we could from each of our study streams. While we hope to use these recordings to analyze potential differences in frog calling behaviors across land-use types, this work also contributed to the larger purpose of growing the existing library of frog calls that exists for the island of Borneo. An eventual goal of Dr. Sheridan’s is to use call recordings to train AI models to identify which frogs are calling in a given “soundscape,” or audio recording, taken from a natural space. This would allow researchers to gauge the diversity of frog populations in a given region without having to perform intensive survey work, saving time and resources in the urgent quest to quantify amphibian biodiversity.

Call recording nights also provided numerous opportunities for me to practice the virtue of patience. There are few better lessons in biding your time than staring directly into the eyes of a frog that immediately ceased to call when the recorder was switched on but had been chirping away mere seconds before. On one memorable night, I sat next to a giant river toad (Phrynoidis juxtasper) for over half an hour as we enjoyed a peaceful and resolutely call-free silence. Fortunately, I managed to record numerous more cooperative individuals during my time in the field.

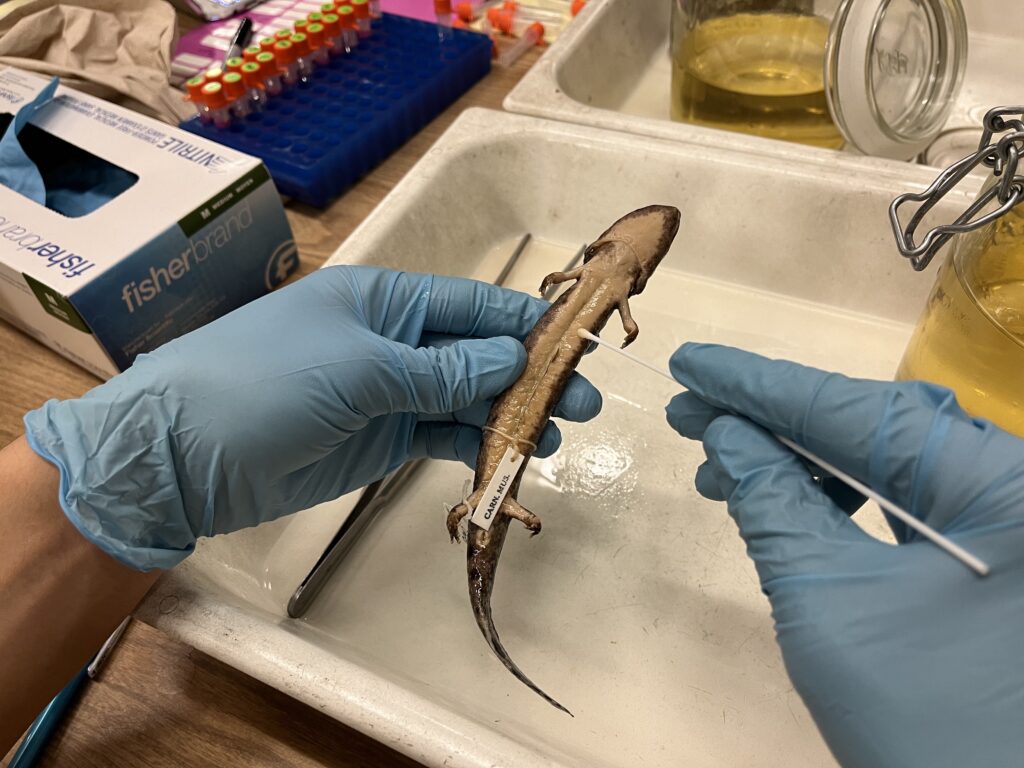

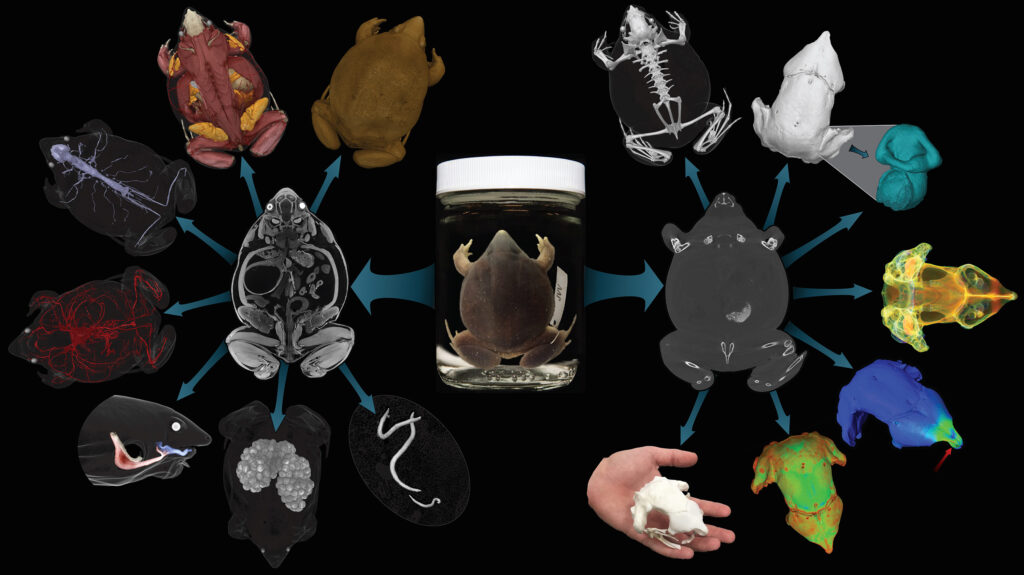

The final facet of our field work involved collecting a limited number of the frogs we encountered at our study streams. These frogs were anesthetized and prepared as specimens to be taken to either the Carnegie Museum of Natural History or to Sabah Parks, one of our local collaborators. Removing animals from the wild and putting them down definitely weighed on me, and I never took that work lightly. However, there are several reasons for collecting frogs in this manner. Collections-based research on frog body size (one of the most important features of a biological organism), specifically regarding whether the body size of a given species has changed over time, is only possible via analysis of preserved specimens of that species spanning a long time scale. Dr. Sheridan recently collaborated on a study that used museum specimens of the Fowler’s toad (Anaxyrus fowleri) to demonstrate that increases in precipitation and temperature between 1931 and 1998 were associated with decreased A. fowleri body size, an important finding given the drastic climatic changes that continue to occur globally today. In addition to its research value, collection allows scientists to document, for posterity, a small portion of the life on Earth from a given spatial and temporal location. This record has the potential to be used to answer future biological questions that we don’t even know to ask yet!

My time working with our amazing team has sadly ended, but the field season will continue for several more weeks as my colleagues wrap up surveys and call recording in our third study region. It is impossible for me to reflect on those months without feeling incredibly grateful for the opportunity to participate in this project. There were so many small moments of joy: my teammate capturing a frog perched on an out-of-reach branch using only a five-meter bamboo stick and gentle coaxing; negotiating stream access with a village leader for two days, only to humorously realize we had a miscommunication about which body of water we actually wished to study; realizing that I had crossed the threshold of seeing over 50 species of frogs in my time in Borneo. Even after two months in the field, I continued to observe fauna I hadn’t seen previously, from river otters to trogons to enormous stick insects. The sheer wonder of experiencing such incredible natural spaces has reaffirmed my goal of ensuring their protection into the future. With Southeast Asia possessing the highest deforestation rates of anywhere in the world, it is more critical than ever to understand the biodiversity that we as conservationists seek to protect. This field season may be coming to a close, but the work is far from over.

Rohan Mandayam was a research assistant on Dr. Jennifer Sheridan‘s field team in Borneo, Malaysia.

Related Content

Nerding Out Over Masting, or Why Unusual Plant Reproduction Excites Animal Ecologists