by Amanda K. Martin

*All research was conducted under approved permits from by IACUC, ODNR, and Metroparks. Do not try this at home with local wildlife. Photos by A. Martin unless noted otherwise.

Where do eastern box turtles go? When I started my graduate schooling in Dr. Karen Root’s lab at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, I was quite intrigued by this question. To address it, I conducted a study of box turtle movements in the Oak Openings Region, the distinctive landscape of oak savannas, woodlands, and wet prairies that stretches across seven counties in Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan.

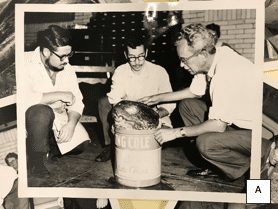

A method called radio telemetry was vital to my work. I walked around under the forest canopy searching for individuals (female or male) and whenever I found one, typically sitting still on the ground, I would pick it up while wearing gloves. In order to track its movements, I attached a radio transmitter onto the carapace (upper shell) using a special type of glue (Fig. 1A). After about a month of searching, I was able to track box turtles at two locations in the Toledo Metroparks system, six individuals in Oak Openings Preserve, and three individuals in Secor Metroparks.

Two to three times a week, I would travel to these local parks and track each turtle using a silver three-pronged antenna and attached receiver. This portable combination detects the signal frequency produced by the transmitter on the tagged turtles, generating a “beeping” sound as it receives the electronic pulse. Guided by “beeps” I could re-find each turtle within an hour (Fig. 1B) depending on how dense the forest understory was. If I walked in the wrong direction, the noise would fade away and become quieter, but as I moved closer to the turtle’s location, the “beeping” sound would get louder and more frequent until I reached the turtle. Sometimes I would walk right past an individual sitting quietly in the leaf litter or under a log as their shell is often highly camouflaged to blend with the sunlit and shadowed patterns of a forest floor. One nice aspect of tracking box turtles with radio telemetry is that they do not run away very quickly, so they are easy to follow!

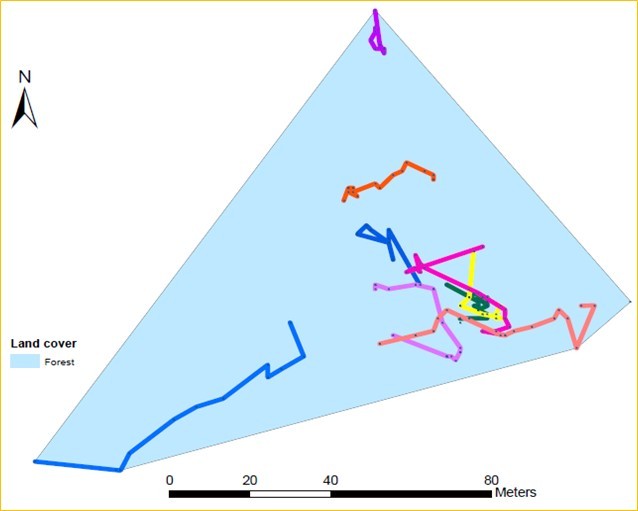

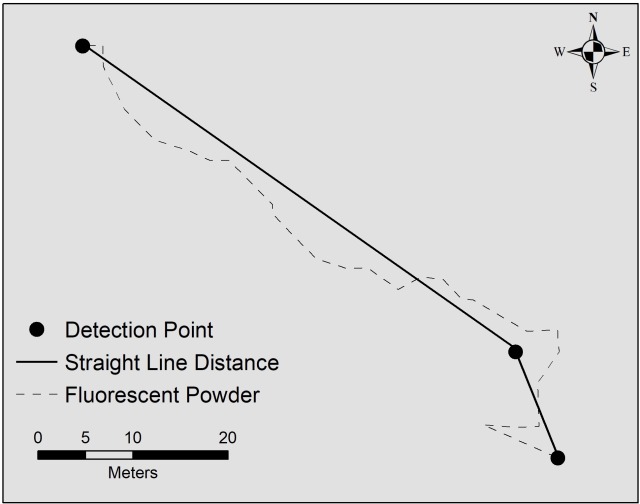

Radio telemetry is an excellent method for re-locating individuals, and provides a snapshot of where the individual is at a given time. With long-term tracking over the active season (mid-March to early November), researchers can better understand movements within a turtle’s home range, the area the animal regularly travels to meet its daily requirements, including food, shelter, and thermoregulation. Home ranges are estimated by drawing an outline around the outermost locations where a turtle was detected throughout the year, and assuming that the individual uses the area inside this boundary (Fig. 2A). Each time a turtle was found, I recorded the GPS coordinates of its location, and could then measure how far the turtle traveled by drawing a straight line between each location point. However, turtles may not always travel in a straight line, but rather follow an indirect route between detection points (Fig. 2B), so this method likely underestimates actual travel distance.

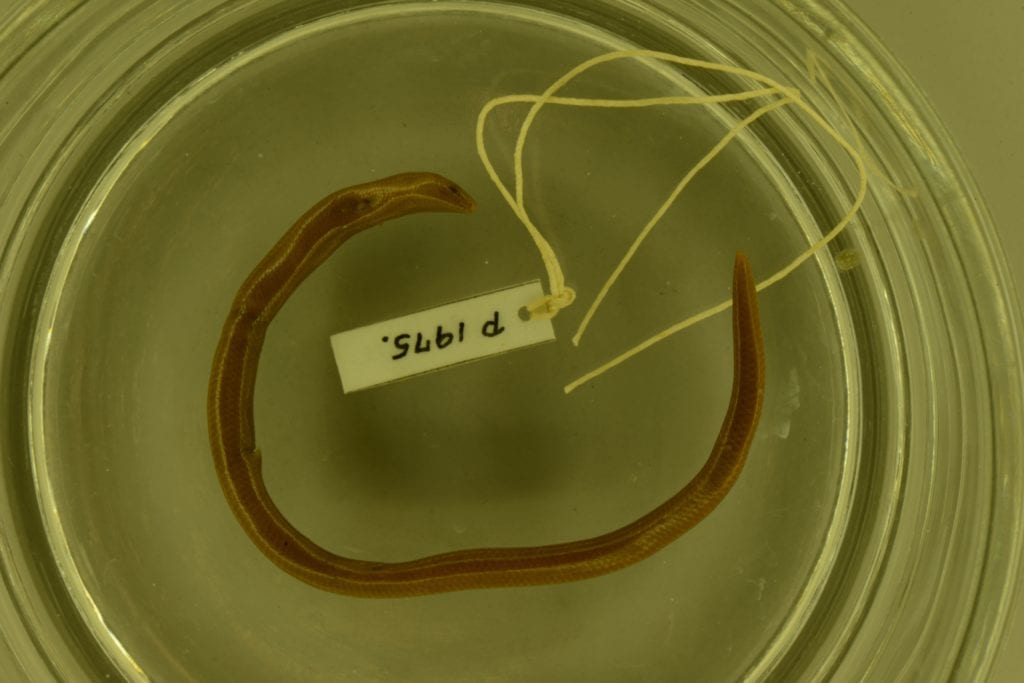

A research technique involving fluorescent powder can produce a far more accurate picture of daily box turtle movements. Non-toxic fluorescent powder is applied to the turtle’s plastron (underside; Fig. 3A) which then leaves a distinct trail as the turtle travels throughout its environment. At night, with the use of an ultraviolet light (Fig. 3B) these trails can then be illuminated, traced, and mapped. Since box turtles tend to travel near or over the same pathways, and because individual home ranges frequently overlap, multiple powder colors are required for some tracking studies.

I used multiple colors (red, blue, yellow, orange) for different days and individuals. The results of my tracking work using this technique demonstrated that box turtles traveled 32 meters per day, with females traveling slightly less than males, and that 95% of movements were less than 6 meters.

Tracking animals with fluorescent powder is more laborious than radio telemetry but demonstrates fine scale movement patterns not detected by radio telemetry. The frequent use of short movements, for example, is likely related to thermoregulation requirements (the need to move in and out of cool, shady patches), or encounters with multiple obstacles ranging from small to large logs, dense shrubs, and trees. Radio telemetry provides an estimation of home range size, while fluorescent powder tracking provides details on how that home range is utilized. In tandem, these research tools can provide important information on habitat use for local land managers, who can facilitate preservation of these reptiles.

For more information on this project, including data on eastern garter snake movements, check out Chapter 4 of my dissertation.

Amanda K. Martin is a Post-doctoral Researcher in Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: How does climate change affect turtle behavior?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Martin, Amanda K.Publication date: April 20, 2021