by Jennifer A. Sheridan

As a herpetologist, I’m often asked whether I see a lot of snakes. To be clear, seeing snakes is always an exciting treat for me. But I’ve come to learn that when people ask this question, they’re usually not asking because they want to hear about all the gorgeous ones I’ve seen, but because they want to gauge how “dangerous” it is to be out and about in the forests where I work. I always explain that snakes are fairly skittish and most will quickly move away from humans, but that yes, I do have the good fortune of seeing some excellent individuals. I especially love Danum Valley, one of my field sites in Borneo, for this reason. Depending on the year, I may be lucky enough to see several species within a short time, and last October I had some great sightings.

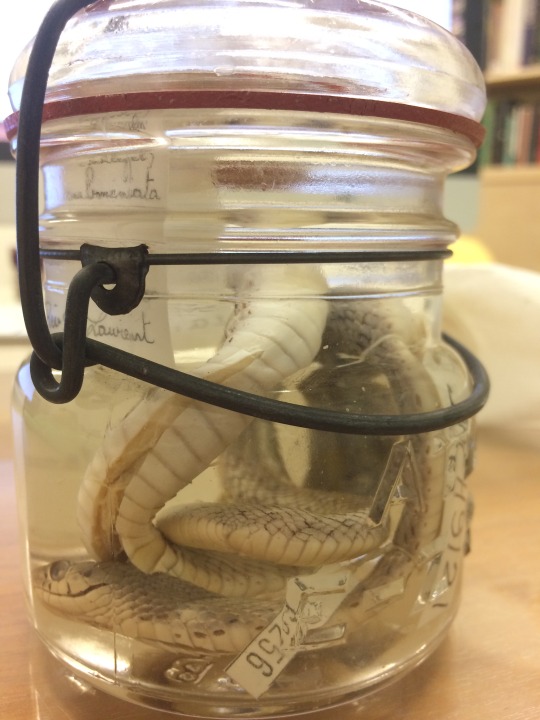

Because I focus on amphibians, most of my work is at night, and mostly along streams. Often, we see snakes on branches as we come into the stream, like this lovely triangle keelback (Xenochrophis triangularis):

Or in the middle of our search for frogs along the stream transect, like this blunt-headed snail-eating snake (Aplopeltura boa):

This species is one of my favorites because it has a big fat head that it uses to hunt for snails. It unhinges its jaw and inserts the lower jaw into the shell to pull out the meat. Sorry, Tim Pearce! 😉

Other times we see snakes swimming in the water as we’re walking upstream, like this baby Python reticulatus:

This was one of the highlights of the trip because a) baby pythons are so cute and b) it had clearly just eaten, so it had a large belly bulge (I feel you, python). When it tried to dive under water, its belly kept floating at the surface and it didn’t really have much luck in hiding away from us. Adorable. (It eventually made its way over to the bank and up into the forest.)

One of the most striking sights, however, had to be this mangrove snake (Boiga dendrophila) swimming downstream towards us, head held up above the water, jet black body lithely undulating behind it. Because of its bright yellow chin and underside, it is extremely striking at night.

One time, years ago, I was in the middle of a transect and the batteries in my headlamp had started to die. I stopped, turned off my light, and changed them out while my teammates continued the survey upstream. When I got my headlamp back on my head and switched it on, a Boigadendrophilawas between my feet. While I am fairly calm in the field, I have to admit that this gave me quite a start! But he went on his way and I went on mine, neither of us all that bothered by the other. So while many people fear snakes, for the vast majority of species if you don’t bother them, they really won’t bother you.

Jennifer A. Sheridan is the Assistant Curator in the Section of Herpetology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Do Snakes Believe in the Tooth Fairy?

Is This What They Call Overkill? Toxin and Venom in the Herp World

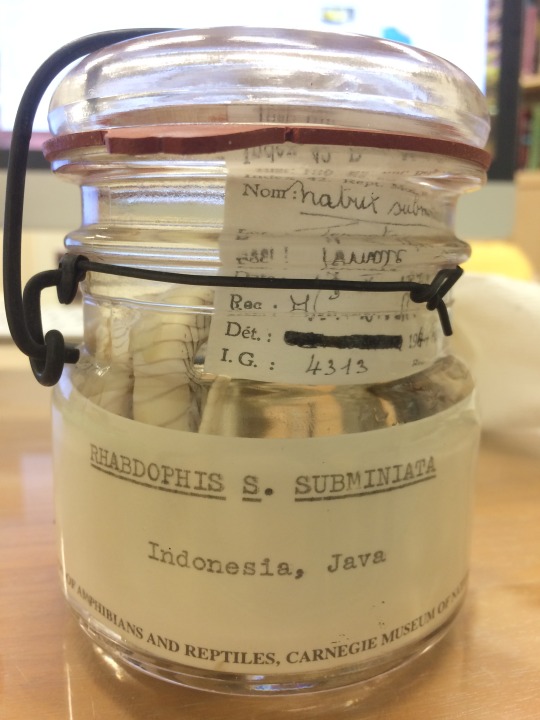

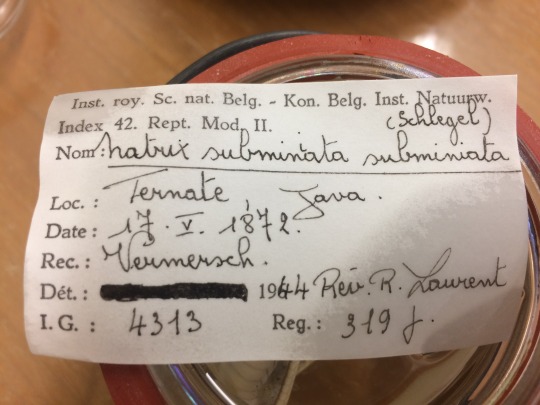

Ask a Scientist: What is an Alcohol House?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Sheridan, Jennifer A.Publication date: March 1, 2019