By James Whitacre

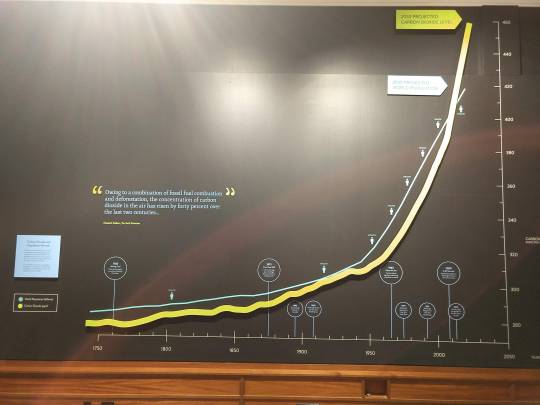

If you have visited the museum recently, you have probably seen the We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene exhibition (if not, you have less than a month to check it out!!). When I walked through the exhibition the first time, I was struck by the image of the surfer gliding across a wave with plastic and other debris floating all around him. It is a bleak image of how the beauty and ecology of our oceans, rivers, and lakes is being tarnished and even destroyed by the accumulation of so much plastic waste.

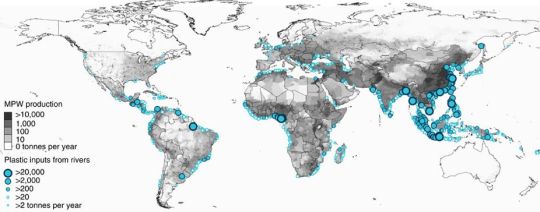

Recently, I also came across an interesting 2017 article, ‘River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans,‘ in which the authors have developed a global model using spatial and temporal data on waste management, population density, and hydrology to measure the amount of plastic in rivers that makes its way into oceans. They found that the top 20 polluting rivers account for 67% of the global total of plastic waste, which is between 1.15 and 2.41 million tonnes of plastic a year. While most of the top 20 rivers are in Asia, and none are in the U.S., their findings have great implications for how plastic waste should be managed and mitigated at global and local scales.

This article got me thinking…How can we, as humans living in the Anthropocene, do something to decrease and even eliminate the accumulation of plastic in our waterways? Many people are thinking about this, but what about our beloved three rivers of Pittsburgh? How much do we as a community contribute to the global plastic waste epidemic? Well, to start answering these questions, we need data to know where the plastic waste is…

How often have you walked through your neighborhood, a local or state park, or even been driving around, and noticed plastic waste (and likely other trash)? With this in mind, we’d like to invite you into an experiment…to help us map Pittsburgh’s plastic waste. The GIS Lab, located at Powdermill Nature Reserve, has developed a simple mapping survey to help track plastic waste in our area. To participate, all you have to do is fill out the form using your GPS-enabled smartphone or mobile device when you encounter plastic waste:

Plastic Waste Survey

What will we do with this data?

Well, right now this is just an experiment…But we are thinking of some cool ways to map and analyze this data. We will definitely share a map that shows the data, so stay tuned. We would also like to help our community understand what happens to the plastic if left in the environment. So, here are some example research questions we hope to shed some light on in the near future:

- If you find some plastic near your house, what stream will it end up in, and what is the shortest path to the ocean from there?

- How much rain or wind would it take to move that plastic to a stream or river?

- Where is the nearest recycling center that I can take a few bags or a large heap of plastic (and other) waste?

Data can be very powerful, and sometimes more powerful than we can imagine on our own. So if you have any other ideas for how we could use this data, please email the GIS Lab!

What is Survey123?

The GIS Lab used Survey123 to build this survey, which is part of the ArcGIS platform. Survey123 for ArcGIS is a simple and intuitive form-centric data gathering solution that makes creating, sharing, and analyzing surveys easy using GIS software. Download the free Survey123 app to use the form we created.

James Whitacre is the GIS Research Scientist for Carnegie Museum of Natural History, where he primarily manages the GIS Lab at Powdermill Nature Reserve, the museum’s environmental research center. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.