Today we use clocks to help us keep track of time, but in the past, humans relied on the planets, stars, and even our sun to mark significant yearly events. A useful tool different cultures independently invented was the sundial—a flat instrument that uses the position of the sun to accurately track the passage of time. You can use some simple supplies to make your own sundial and learn the science behind it! *This activity requires a grown-up!

What You’ll Need

- Paper plate

- Pencil, straw, or a long thin object

- Tape measure or yardstick

- Tape

- Watch or clock

- Ruler

- An outdoor space in natural daylight

- *OPTIONAL* Markers or crayons to decorate

Directions

*For best results, either start earlier in the day or work on this project for multiple days.

- Find your test area—this should be an open space with good natural daylight and away from any shadows. Use chalk or a visual marker to mark this area.

- Stand in your area and have a grownup trace the outline of your shadow on the ground with chalk. Write the current time at the top of your shadow.

- Use a pencil or pen to poke a hole through the center of the paper plate

- Write down the time on the edge of your plate. Use a ruler to draw a straight line from the number you wrote to the hole in the center of the plate.

- Take your plate and plastic straw outside and place on the ground in your marked area. Slant the straw so that it points to the line you drew on the ground

- Rotate the plate so that the shadow of the straw lines up with the line you drew

- Place some stones on the plate to keep in place, but be careful not to tip over the straw

- Check on your plate every hour. What happened to the shadow of the straw?

- Record the position of the shadow of the straw by writing the current time on the edge of the plate where the shadow falls. What shape is your shadow moving in? What does this remind you of?

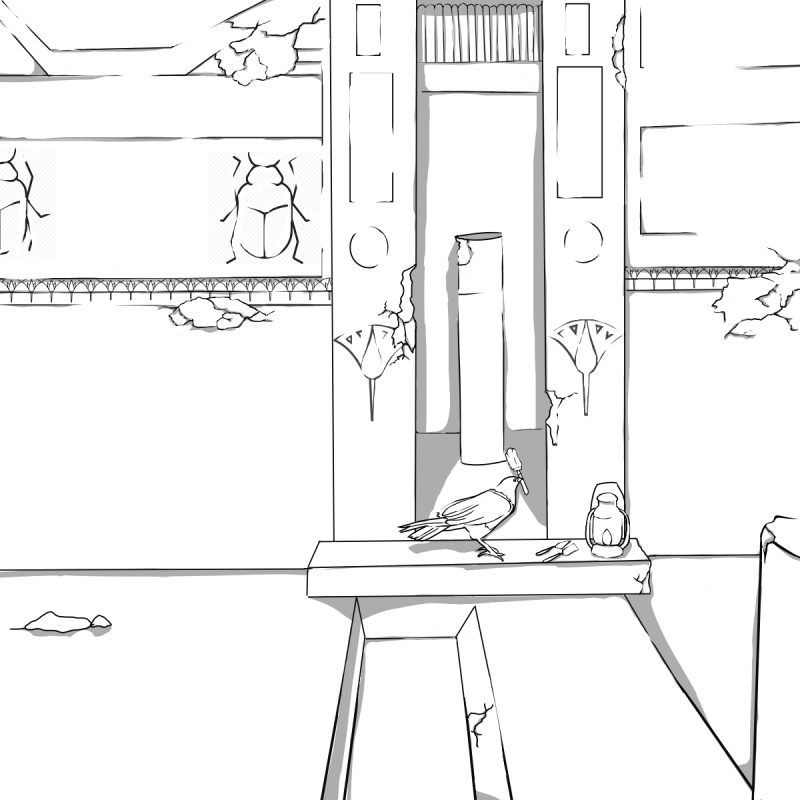

So, what’s the science behind the dial? Sundials come in many different forms depending on which cultures used them, but they have two key common features—they’re typically made on flat platforms or surfaces and have a thin, upright rod that casts a shadow on the dial called a gnomon. The reason the shadow moves so precisely on the flat platform is due to the Earth’s rotating axis; as the earth rotates around the sun, the shadows on earth change position as well.

Sundials aren’t just a part of ancient history, either; sundials were commonly used as late as the 16th century!

The next time you see a clock, whether a digital or an analog clock on the wall, remember that these inventions and so many others we use day-to-day have very ancient beginnings!