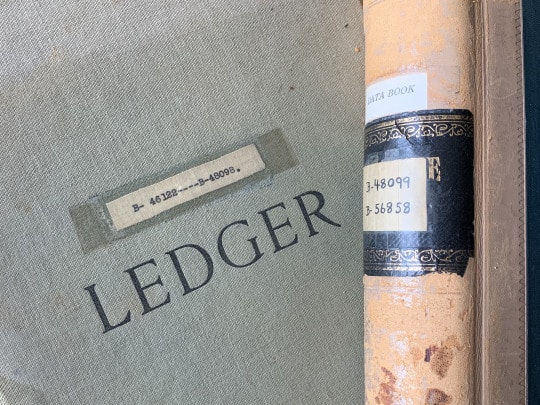

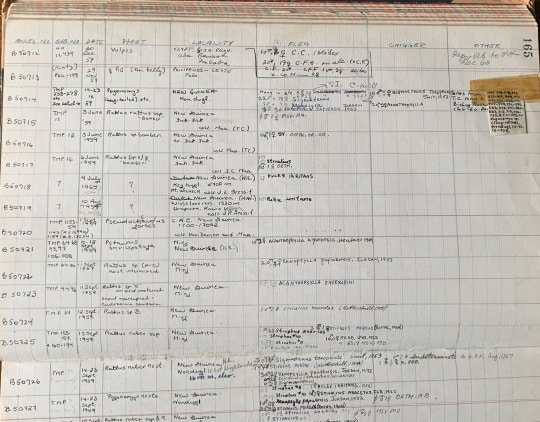

With work-from-home restrictions in place, I’ve been transcribing the handwritten field notes (Figures 1-2) of world-renowned flea expert Robert Traub into a digital database. Between 1995 and 1997, Traub donated most of his collection to CMNH. Materials housed in the Traub collection span the globe, from the middle east to central America to islands in the pacific and beyond. The notebook I’m currently transcribing dates back to the mid-1900s, with records from particular field expeditions to Pakistan and Mexico.

This type of retroactive data capture allows us to put standard locality information on specimens formerly associated with just an identification or data code number. This process also allows us to verify and update taxonomic names as necessary. While it’s not nearly as fun as field work, data capture and transcribing are still an important part of collections work.

The Traub collection is estimated to contain nearly 75,000 specimens mounted on glass slides (Figure 3), with 5,000 associated genitalic dissections. The enormous collection is housed in antique cabinetry as well as modern Eberbach cabinets. Almost 7,000 of these specimens only have a data code; thus, my digitization efforts and subsequent labeling continue!

Since I started working in IZ nearly three years ago, I have had the distinct privilege of working with different taxa every few months. From Lepidoptera, to Odonata, to Coleoptera, to Arachnida, and now Siphonaptera, these tasks serve as beautiful reminders of the diversity of life here on planet Earth.

Catherine Giles is Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.