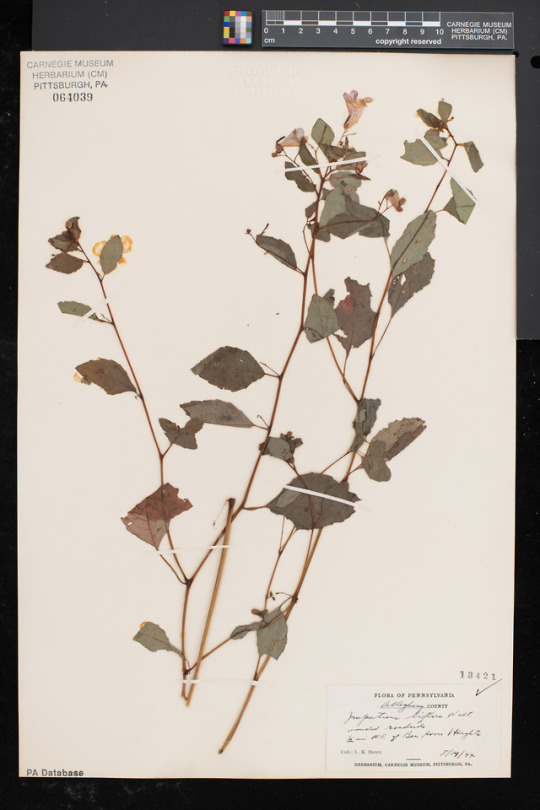

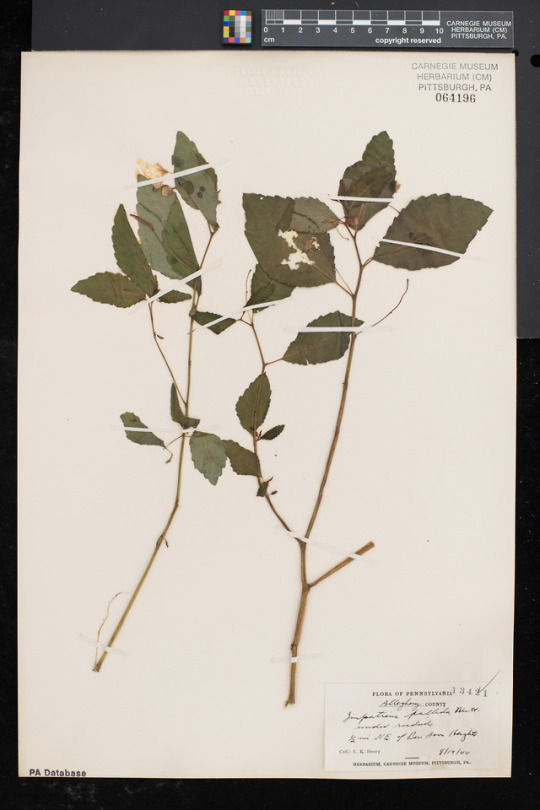

Two specimens of jewelweed, Impatiens, collected on this day (well, yesterday) by Carnegie Museum curator Leroy Henry in 1944 in Ben Avon Heights, near Pittsburgh.

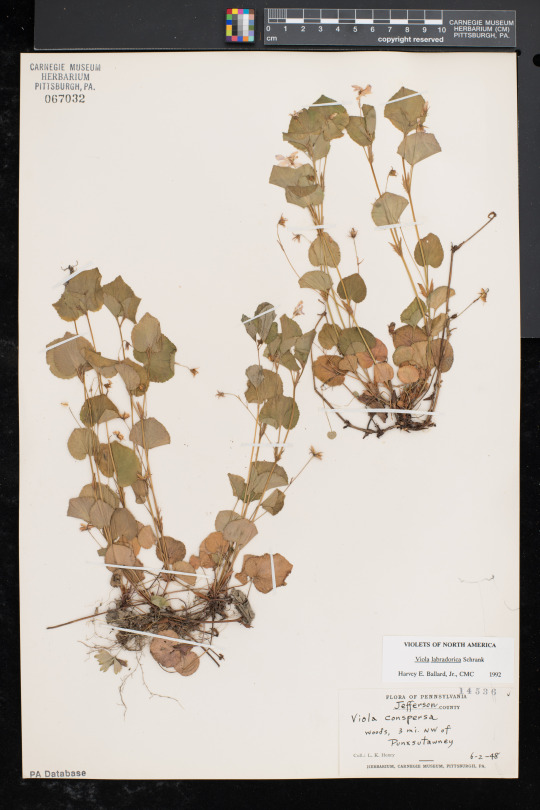

There are two species of jewelweed commonly found in Pennsylvania and in relatively wet, partly shady habitats across eastern North America. They can form dense stands along wet roadside ditches at edge of woods and in floodplain forests. Henry collected both species in the same location, as they commonly grow together.

What’s the difference between these two specimens? Though less obvious in specimen form, the most noticeable difference is flower color. Common jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), also called spotted or orange jewelweed, has orange flowers. In contrast, the flowers of yellow jewelweed (Impatiens pallida), also called pale jewelweed, are…well, yellow. Flowers of both species have distinctive nectar spurs that jut out of the back of the flower. It is entertaining to watch bumblebees go from flower to flower in a stand of jewelweed.

Jewelweeds are herbaceous, annual plants with juicy stems that can range in size, from short to very tall. A widespread story is that jewelweed can treat skin irritations, and in particular, helps prevent poison ivy rash by rubbing jewelweed on skin after contact with poison ivy. I don’t know of this being supported with data.

Jewelweed is also often called “touch-me-not” because the developed seed pods eject seeds out when touched. It can be a fun activity for kids (and adults).

Jewelweed flowers open mid-summer and the plants continue to flower until killed by autumn frost.

Jewelweed produces two types of flowers – the obvious ones with nectar spurs that are visited by bees and also, tiny inconspicuous flowers that do not open. These small flowers are self-pollinating (cleistogamous).

Deer often eat jewelweed. A recent study found that some populations of the species that have historically received a lot of deer browsing have evolved greater tolerance to herbivory.

I’m always amazed how sensitive jewelweed leaves are to the sun. When exposed to direct sun, their leaves get very droopy. But they seem to quickly bounce back.

Impatiens commonly planted in gardens are related (in the same genus) but are not the same species.

Check out these specimens (and more!) here.

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They have embarked on a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.