by Joann Wilson and Albert Kollar

“I am reluctantly, arriving at the opinion, that I am the victim of an imposition for which I hold you responsible.” –Frederick Stearns in a letter to Ernest Bayet, March 27, 1889

In 1903, Andrew Carnegie purchased the world-famous Bayet fossil collection for the Carnegie Museum. Since that time some invertebrates in the massive 130,000 specimen collection have been thoroughly studied, but the documents that arrived with the fossil shipment remained largely unexamined. Reasons for this neglect are understandable. The collection’s accompanying letters, lists, journals, and other documents were written primarily in French, German, and Italian, and in what has been described as “an impenetrable hand.”

Translation of the documents into English was a critical step in making them better known to researchers and the public. As part of Albert Kollar’s multiyear project to restudy the invertebrate portion of the Bayet Collection, that difficult task is ongoing thanks to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers, a resident of the Netherlands.

The translated documents bring some life to the people behind the famous fossils, and our series begins with one of them, Frederick Stearns.

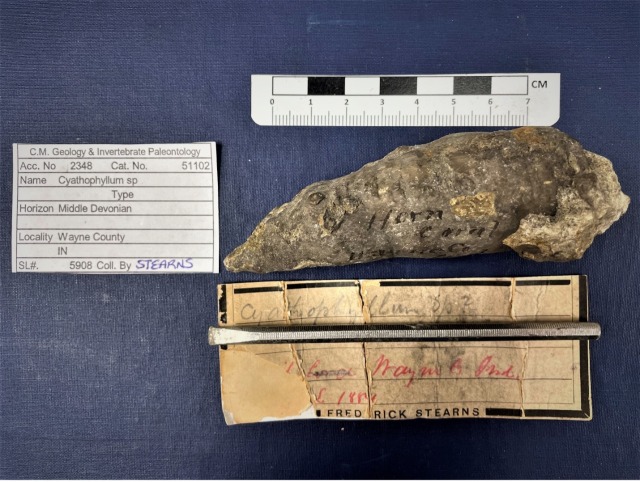

Which gets us back to the letter excerpted above. One wonders what Ernest Bayet thought in the spring of 1889 when he opened it. Bayet, who would become secretary to the cabinet of Leopold II, and Frederick Stearns of Detroit, Michigan, a retired pharmaceutical executive, business owner, and renowned fossil collector, had settled on a sizable trade deal. Stearns was to send over “1000 species of fossils” from the United States. In return, Bayet was to ship “5500 species of shells.”

Stearns had shipped his lot of fossils, but by spring of 1889, he had yet to receive a shipment from Bayet. Fuming, he wrote, “to obtain legal redress through the advice of the American Minister at Brussels. Failing in this I stand ready to spend 2500 francs or even 5000 francs if necessary, to advertise you, and your way of doing things to the Scientific World. In doing which I shall at least have the satisfaction of check mating any similar future operations of the sort with other persons as credulous of your honor and integrity.” In current figures, Stearns was willing to spend $15,000-$30,000.

Stearns ended, “with this for warning, I subscribe myself indignantly etc.” After this letter, no more correspondence is known to exist between the two men. Did Bayet send his lot? As part of Albert’s project to investigate the individuals behind the Bayet Collection, we wondered, was it possible to solve this mystery over a century later?

Research into Stearns revealed that he collected more than fossils and shells. Carol Stepanchuk, Collection Outreach Program Coordinator for the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments at the University of Michigan, provided a valuable starting point. With her guidance, and a hunch that Stearns may have left his other collections to the University of Michigan, we reached out across the Ann Arbor campus to Jennifer Bauer, Research Museum Collection Manager at the University’s Museum of Paleontology. Jennifer added Taehwan Lee, the museum’s Mollusk Collection Manager, to the search. After many months, our story has a happy ending. Jennifer and Taehwan located over 5000 specimens in the U-M collections, donated by Frederick Stearns, with “Bayet” as collector. Thanks to museum collections records and the amazing team at U-M, we now know that Ernest Bayet did send his shells!

In Part 2 of our series, we will take a look at the unusual path that brought Frederick Stearns into contact with Ernest Bayet and fossil collecting. As John Carter, former Curator of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural history, once wrote about the Bayet Collection, “The best measure of the worth of this treasure trove, however, is not its size but its uniqueness. Many of the individual collections, all made in the nineteenth century, are essentially irreplaceable, because similar specimens from the same collecting localities are no longer available.”

Many thanks to the generous contributions of Carol Stepanchuk, Collection Outreach Coordinator for the U-M Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments, Joseph Gascho, Associate Professor at the U-M School of Music and Director of the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments, Jennifer Bauer, Research Collection Manager at the U-M Museum of Paleontology, Taehwan Lee, Mollusk Collection Manager at the U-M Zoology Museum and volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers for meticulous language translation.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter for the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

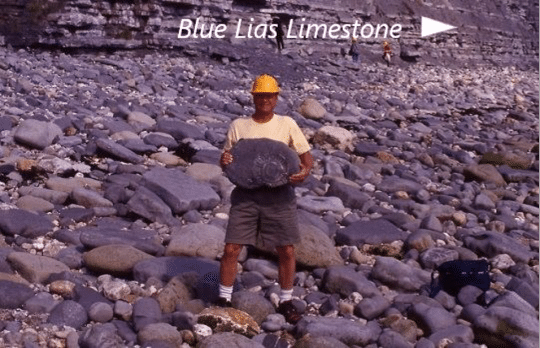

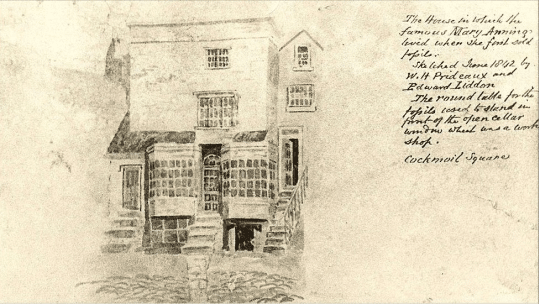

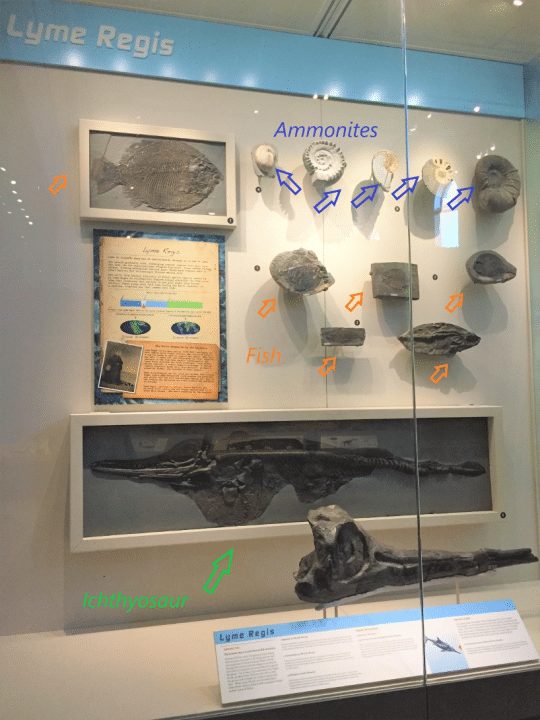

Mary Anning: For the Love of the Blue Lias

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wilson, Joann; Kollar, AlbertPublication date: April 23, 2021