By Vanessa Verdecia

Many people wonder: “what happens to bugs during the winter months?” In the case of Callosamia promethea, known as the Promethea Moth, the caterpillars will have spun a cocoon in a leaf and will spend the winter as a pupa in a cocoon that is well attached by silk and hanging from a tree. This is the third stage of metamorphosis before the adult moth ecloses (=emerges) the following summer and is seen flying during June-July in Pennsylvania. You may look for these cocoons in the winter as they are usually found on low-hanging branches of many types of forest trees.

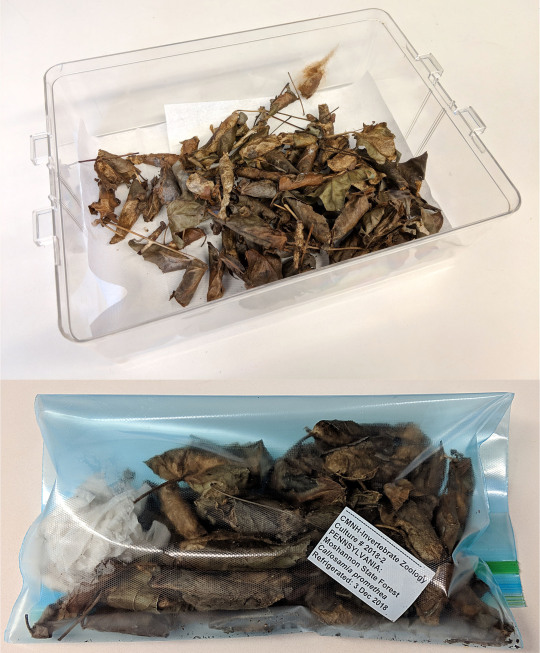

This year in Invertebrate Zoology we reared Promethea caterpillars and we are now ready to mimic winter conditions in the lab. The live cocoons have been carefully stored in a sealed plastic bag with a damp paper towel to maintain humidity. This bag has been stored in the refrigerator to mimic the cold temperature that the cocoons would have experienced outside. Insects are sensitive to temperature cues that will dictate when the moth is ready to eclose. Experiencing diapause—a period of suspended development—will trigger the moths to eclose the following year. The cocoons will remain in the refrigerator until next spring, and hopefully they will survive and we’ll have some beautiful moths eclose. Insects are also dependent on light cues and are sensitive to day length, which is more difficult to mimic in a lab setting. I am hopeful these will survive, as this technique has worked in the past.

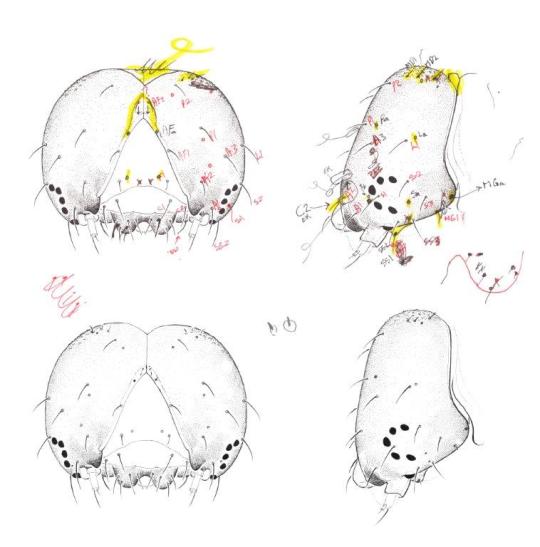

This process will conclude the full cycle of an isofemale rearing in which all of the stages of metamorphosis were observed and documented. We have the wild-caught male and female adult parents. At each stage of development, specimens were chosen to be preserved in order to document the egg, larval, and pupal stages. These specimens serve as a reference for associating the developmental stages of a single species, as documented in a reared culture from a single parent.

Go ahead and look around because this is the perfect time of the year to see Promethea moth cocoons decking the trees of the forest this holiday season!

Vanessa Verdecia is a collection assistant in the museum’s Invertebrate Zoology Section. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.