by Debra Wilson

The naming of minerals has changed over time from its alchemistic beginnings to the advanced science of today. During this span minerals have usually been named for their physical characteristics, the locality where they were discovered, or a person. I have often been asked, “why do most mineral names end in ite?” The suffix “ite” is derived from the Greek word ites, the adjectival form of lithos, which means rock or stone.

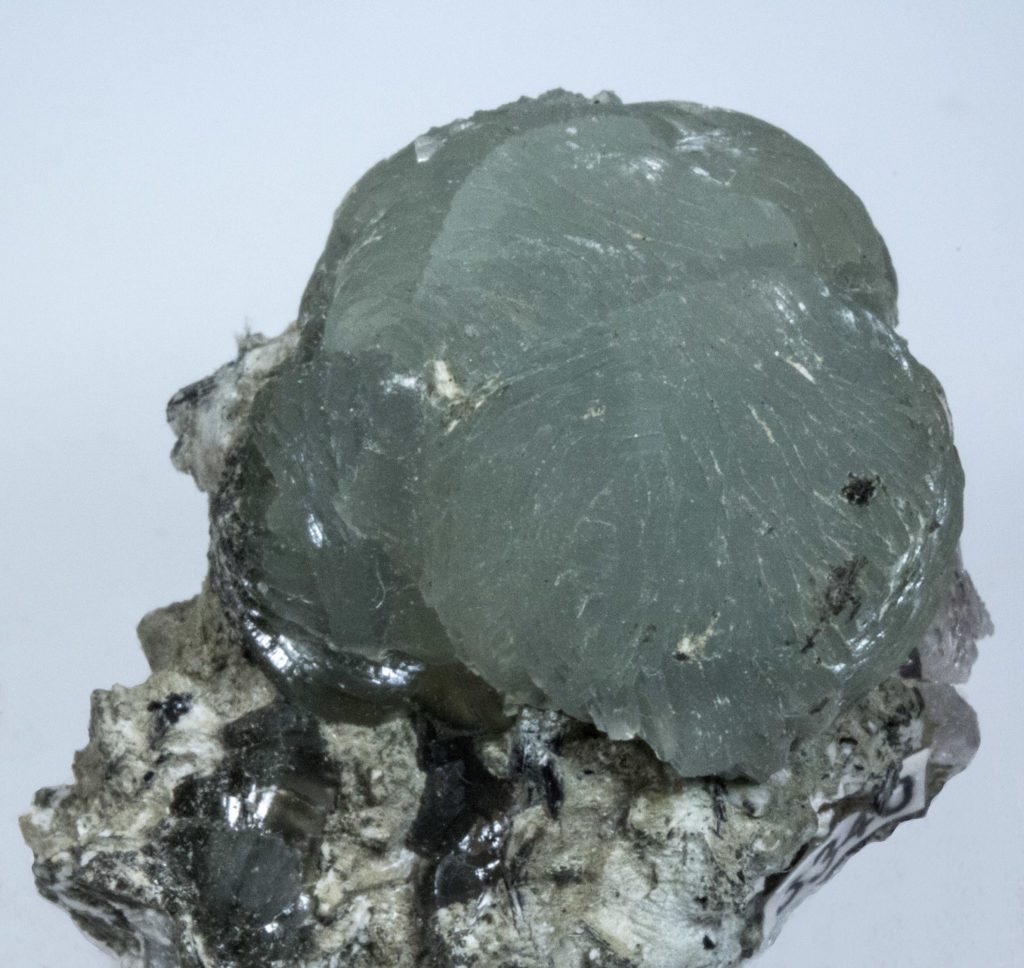

In antiquity, distinctive physical characteristics were often the source for the mineral name. One of these properties is color. For example, Malachite probably comes from the Greek word malakee or malache, used to describe the green leaves of the mallow bush. Azurite comes from azure, the Arabic word for blue, and Kyanite comes from kyanos, the Greek word for blue.

With the advancement of science, some minerals have been named for their chemistry or their structure. For example, Cavansite is named for its chemistry (calcium vanadium silicate), and Pentagonite is named for its five-fold symmetry (a pentagon is five-sided).

Minerals named for the first locality where they were found are quite obvious for those with a knack for geography: Elbaite was found on the Isle of Elba, Italy; Goosecreekite was found in the New Goose Creek Quarry in Leesburg, Virginia, and Ilmenite was found in the Ilmen Mountains of Russia; to name a few.

Minerals have also been named for people. Prehnite was the first mineral named for a person, Colonel Hendrik Von Prehn (1733-1785), who is credited with discovering the mineral in 1774 at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. Cordierite, a mineral known for its iolite gem variety, was named in 1813 for French mineralogist Louis Cordier (1777-1861), a pioneer in the field of microscopic mineralogy, and in honor of her pioneering research on radioactivity, Marie Sklodowska Curie (1867-1934) had two uranium minerals named for her, Sklodowskite (discovered in 1924) and Cuprosklodowskite (discovered in 1933).

Today new minerals, including the proposed species name, are approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (CNMNC), under the purview of International Mineralogical Association (IMA), which was formed in 1958. As of November 2021, the IMA recognizes 5,762 official mineral species. In October 2021, one of those species, Oldsite, was named in honor of one of our own museum scientists, Travis Olds, Assistant Curator of Minerals, for his contributions to uranium mineralogy.

Congratulations Travis!

More information about Dr. Travis Olds

Debra Wilson is the Collection Manager for the Section of Minerals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wilson, DebraPublication date: January 14, 2022