From the first blooms of spring through the end of summer, insects (and many other things we often call bugs), are plentiful. They make their presence known at all hours by buzzing along during the day and chirping throughout the night. But where were they all winter? There is no one answer and that is what makes it so fascinating! Let’s take a closer look at where the insects we are seeing now have been hiding.

Flying South for the Winter

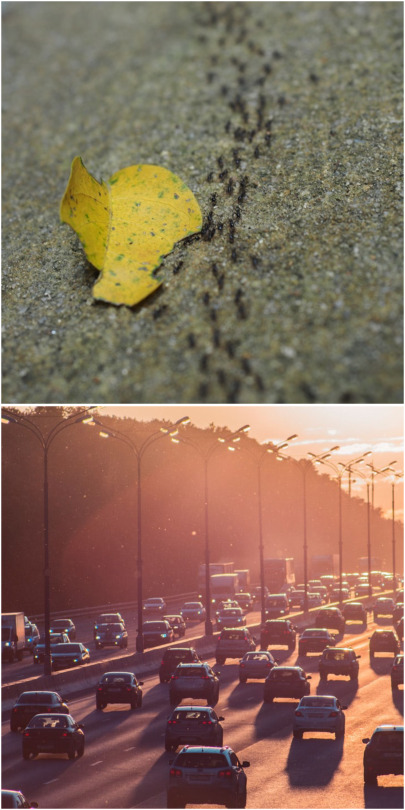

When we think of migration, we usually attribute it to birds. However, insects are known to migrate as well. Generations of monarch butterflies from the United States and Canada fly south to Mexico and roost in mountain forests. Different species of dragonflies also migrate. In the US and Canada, adults of migrating species leave for Mexico in the early fall and return in the early spring. What’s really amazing is that the young larvae stick around in our winter creeks and rivers, and hatch into adults in the spring.

The Next Generation

The end of fall can mean the end of a life cycle for many insects. To keep their species going, they lay eggs in the fall that either survive the cold as larvae or hatch in the spring. This is known as overwintering. Young woolly bear caterpillars find shelter in the cover of decaying leaves and logs or under rocks. Those praying mantises you see in the spring and summer? They hatched from eggs that survived the winter. Mayfly nymphs live in the water, even under ice, and are known to feed and grow all winter.

Yawn…See Ya in the Spring

That’s right, some insects even hibernate. Honey bees will group together in their hive and keep each other warm by slowly flapping their wings to generate heat. Certain arthropods like isopods can even produce a kind of antifreeze known as glycerol that keeps them from freezing. Now that spring is here, it’s the perfect opportunity to observe flowers in a garden, park or street and see what insects visit. You can also note these in the iNaturalist app during the City Nature Challenge.

A Buggy Challenge

How many photos of insects can you take and share on the free iNaturalist app during the 2020 City Nature Challenge, April 24-27.

Let’s Play Bug Bingo!

Get three in a row and you win! Head outside and cross off each insect (or other type of arthropod) that you see, in the order in which you spot it. Give yourself a bonus point each time you snap a picture and upload it to the iNaturalist app (with your parents’ permission!) during the City Nature Challenge that takes place April 24-27! Have socially distant fun with family and friends to see who can get bingo and then collect the most bonus points.