Careers in librarianship are often depicted as quiet, solitary positions that allow ample time for reading on the job. Images associated with archival librarianship (a career usually pertaining to the collection, preservation, and management of historically relevant materials) get even more visually specific than the first, for they frequently involve mahogany framed spaces filled to the brim with dusty, leather-bound, centuries-old texts. Though whimsical, these notions about texts and their caretakers cause people to overlook a critical part of archival work: digital management of texts and data.

Our society’s emphasis on the importance of technological advances and virtual storage has not only advanced the librarian’s ability to scan and virtually distribute texts and documents with ease; it has also gone so far as to set the expectation that archival texts will be digitized, or converted into a digital form. This digitization both protects data from being lost to physical damage and, through mechanisms like databases, helps interested people gain greater levels of insight into the exciting and unique collections that exist around the world.

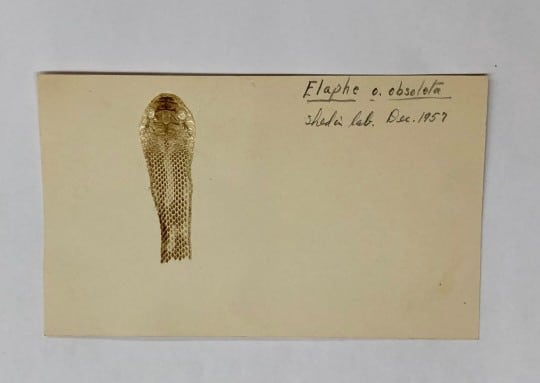

While libraries have always housed a wide range of texts and items from a variety of professional fields, the level of priority placed on digitizing archival collections has ultimately allowed for even more crossover between people of different professional backgrounds. My job in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles is a prime example of this. Though I have been entrusted with caring for and scanning the section’s 20th-century field notebooks, my area of expertise is not herpetological by any means. I come from a strictly literary background, with my research focusing on 19th-century magazines for children. How, then, do these professional paths intersect?

Apart from the fact that I have handled older texts before, my background and the needs of the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles exist in harmony because of a mutual recognition of the value of accessibility. While working with archival databases through transcription-based volunteer projects and past research positions, I learned that accessibility is as much about small details as it is about sharing the museum’s materials with other institutions and, ultimately, the public. For example, if my scans are too dark or are surrounded by too much black space, the readability of the document may be affected and people with limited access to printer ink may not be able to make copies of the material. Digitization may appear to simply prevent a loss of information, but the need for accessibility causes it to take on new meaning. As a future archivist, I prioritize scan quality and the organization of digital files so that museum employees and the public alike can always find and use these important scientific materials with ease. Though we come from different fields, the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles consistently prioritizes its concern with the use of these materials in the long run as well.

I am grateful that I am continuing to learn about the relevance of scientific specializations like herpetology to other fields. Likewise, I am glad that my understanding of librarianship continues to intersect with fields that I may not otherwise encounter. Perhaps, then, popular depictions of librarians and archivists can begin to recognize their preoccupation not only with reading and quieting patrons, but also with collaborating across disciplines to expand people’s access to information.

Ren Jordan is a Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is the creepiest specimen in the Alcohol House?