by Jennifer Sheridan

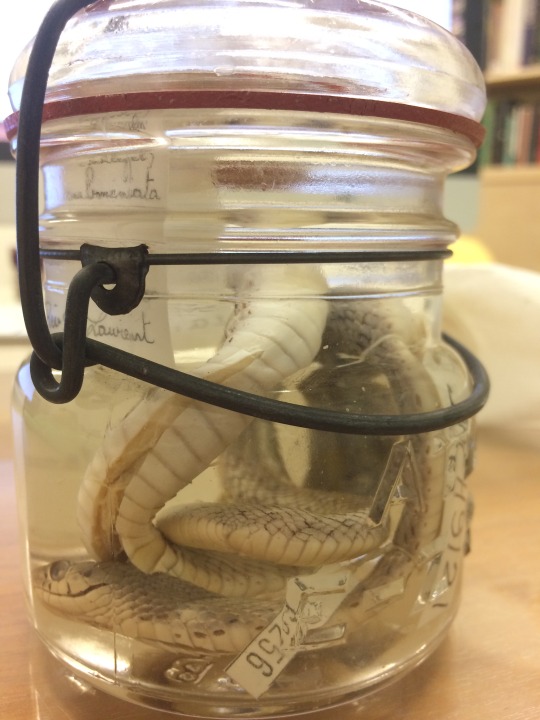

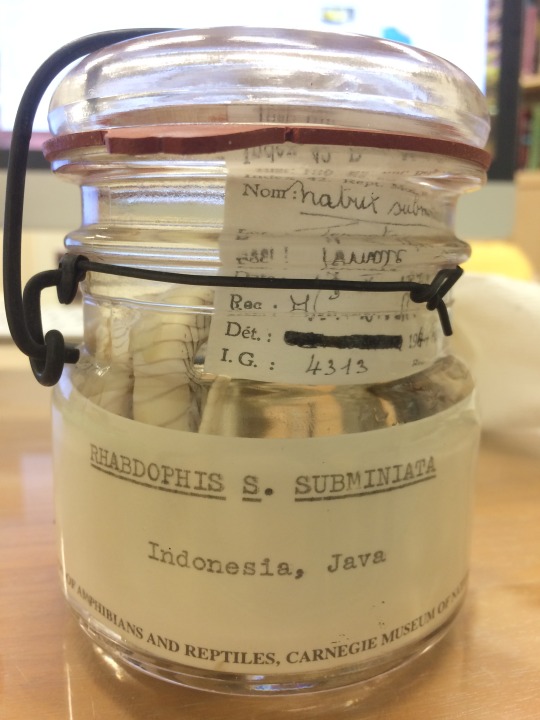

Part of the fun of being a new curator is getting to know the collections. In preparing for an upcoming talk (Scientists Live on Facebook on September 19th), I was sorting through our collections database to see what specimens we have from Southeast Asia, where I do most of my research. I came across a record that intrigued me: a fairly common snake (Rhabdophis subminiatus) from a potentially uncommon locality. The jar label says “Indonesia, Java”—Java being one of the islands in the Indonesian archipelago, which also happens to be the world’s most populous island. But the exact location detail is what caught my eye: Ternate.

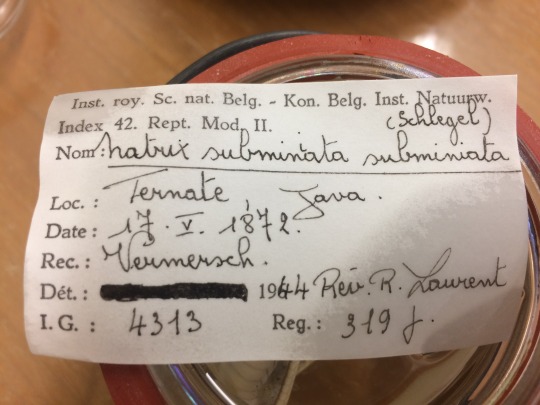

If you happen to be from Southeast Asia or you’re a biogeography buff, you may know that Ternate is not in fact on Java, but is itself a tiny island in eastern Indonesia, off the coast of Halmahera, which is part of the Maluku group. Biogeographically this area is interesting because it lies just east of Wallace’s Line, an imaginary dividing line that separates the flora and fauna of Sundaland (mainland Southeast Asia) from that of Austronesia (Australia, New Guinea, and associated islands). This area played a key role in our understanding of biogeography because it was while he was traveling across Indonesia that Alfred Russel Wallace noticed that there was a very distinct change in the species of plants and animals found in Borneo and Bali (west of the line), compared to those on Sulawesi and Lombok (east of the line), despite the fact that those islands are not separated by a large distance. He noted this in his journals and scientists later named this dividing line after him, once they learned that the plants and animals west of the line originated in mainland SE Asia, while those east of the line originated in Australia.

But Ternate is interesting not simply because of its geographic location, but because of Wallace’s relationship to it. Ternate is where Wallace was when he wrote his famous letter to Charles Darwin in 1858, while laid up in bed with fever, explaining to Darwin his idea of evolution by natural selection. Amazingly these two people had arrived at the same idea totally independently of one another, half a world apart. They had shared correspondence prior to 1858, and it was this letter from Wallace that prompted Darwin to jointly publish his own work alongside Wallace’s, thus introducing to the world for the first time the idea of evolution by natural selection, which has allowed us to understand the natural world.

Coming back to the specimen, I had been hoping that perhaps it was collected by Wallace or one of his team, but the record is from 1872, ten years after Wallace had returned to England. The listed collector, Vermersch, is not a collector known to me or other herpetologists I’ve checked with who work in SE Asia, and we have no additional details on the specimen. Given that I cannot find a record of a city called Ternate on the island of Java, and the fact that all of Indonesia may have been known as the Java Sultanate at the time, my guess is that this specimen is actually from Ternate, and not Java proper. This specimen also has the distinction of being one of our oldest, so for me, and anyone else studying biogeography of SE Asia, this specimen becomes doubly interesting and valuable, and will definitely be one of the highlights of any upcoming tours of the Alcohol House! I’m looking forward to finding more secret treasures as I get to know our collection.

Jennifer A. Sheridan is the Assistant Curator in the Section of Herpetology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.