by Sabrina Spiher Robinson and Tim Pearce

Imagine you’re a clam, hanging out in your cozy little hole under shallow ocean water, with your siphon out, just filtering lunch out of the water current, happy as a…you. Then, all of a sudden, something flips you gently out of that hole.

You pull in your siphon and your foot, clamp shut your valves. You’re pretty tough to get open, strong adductor muscles keep your two shells held tightly together, and you’ve survived danger by closing up shop and waiting before. And nothing seems to be trying to pry you open, even though something has wrapped itself around you, and is now pulling you down into the sand with it. Then:

scrape scrape scrape

scrape scrape scrape

scrape scrape scrape

Or imagine you’re a young moon snail, Neverita duplicata – one of the most common species of moon snails that live on the eastern seaboard of North America. You’re a gastropod with a lovely round grayish shell, such that people call it a “shark eye,” and you’ve got a huge foot that can come out of that shell and cover almost all of your body – or all of your prey’s body! But at the moment you’re just cruising along the sand, slurping at a bit of detritus. Suddenly, you’re enveloped by something. You instinctively pull your body into your shell and tightly close your door-like operculum for safety. Then your aperture is covered by…something familiar? Then:

scrape scrape scrape

scrape scrape scrape

scrape scrape scrape

It doesn’t matter how tightly the clam clamps, or how mighty the young snail’s foot, both are going to come to the same fate, slowly.

scrape scrape scrape

scrape scrape scrape

scrape scrape scrape

Eventually, your shell is penetrated. A rasping radula – a mollusk’s organ containing its teeth – has bored a hole through your shell with the help of a gentle acid secreted by a gland by the mouth, and then you feel a burning: gastric juices are being pumped through the hole to begin to digest your flesh. Your killer begins to slurp you up, right where you lie, wrapped up in their hug, as you’re slowly eaten alive.

The young moon snail might have figured out who its killer was before the end: that’s how it eats too. The thing is, moon snails are cannibals, the larger preying on the smaller.

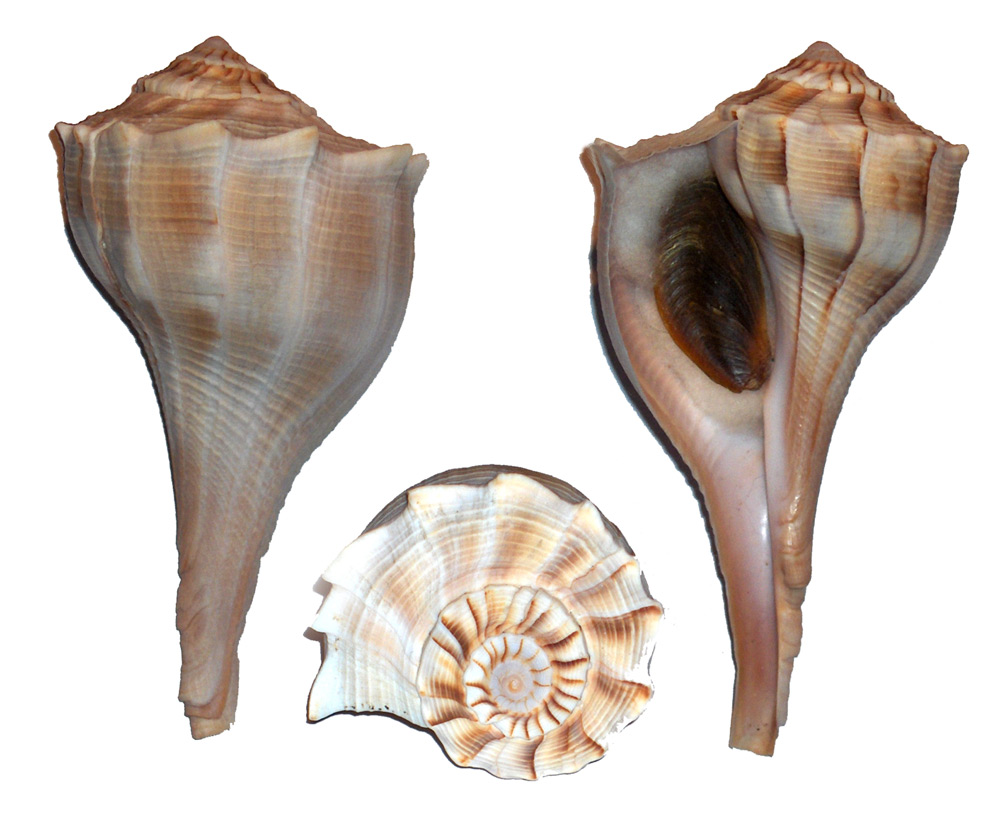

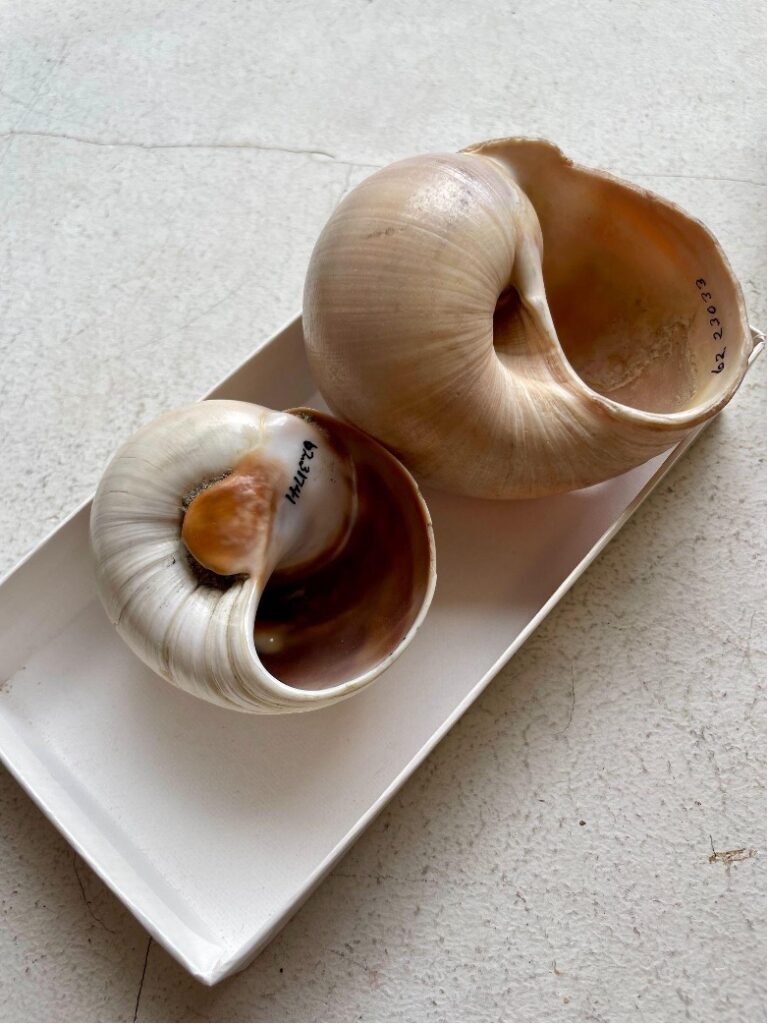

There are hundreds of kinds of moon snails all over the world, but the ones that are probably most familiar to beach goers on the eastern coast of the USA are two species also commonly called “shark eyes” – Neverita duplicata and Euspira heros. From the top, they’re hard to tell apart (the spire on E. heros is a little pointier than on N. duplicata) but once you flip them over, it becomes easy to distinguish them: N. duplicata, the Atlantic moon snail, has a big callus over its umbilicus, and E. heros, the Northern moon snail, doesn’t. Technically, only the Atlantic moon snail has a shark eye shell, but since they’re often mixed up with Northern moon snails, the term shark eye is sometimes applied to them too.

These two moon snails aren’t the only marine gastropods that drill their prey and digest them alive to suck them up for dinner – lots of marine gastropods are predatory drills. But moon snails have distinct boreholes that allow people to identify when a shell has been bored specifically by a moon snail – scientists can even tell the difference between the Atlantic and Northern species’ holes. These “countersunk” holes look like little funnels, wider on the outside of the shell than on the inside. Other kinds of drilling snails leave behind straight-sided holes.

These unique boreholes allow scientists to track the evolution of moon snails from the Miocene to recent times. One group of researchers found that moon snail cannibalism might have driven a kind of coevolution between and among moon snail species. Because one moon snail can make dangerous prey for a fellow moon snail predator, over time moon snails seem to have learned to drill other moon snails at a spot on their shells that allowed the predator to cover the prey’s entire aperture, preventing the strong foot of their prey from fighting back. This means boring through a thicker part of the shell, however, so it takes longer to hold down and bore through the prey snail’s shell. But the record of natural selection in fossils throughout time suggests the added cost must be worth the benefit of moving target drilling zones. Meanwhile, small moon snails almost always lose out to larger ones when attacked, so both N. duplicata and E. heros have evolved to get bigger and bigger over time – although a bigger snail is also a more enticing snack target. Same-sized moon snails don’t even bother to attack one another, suggesting that a fellow moon snail is just too dangerous a prey when the winner of the battle between snails is a toss-up. As evidence that these are often battles between predator and prey snails, there are many incomplete boreholes found – a moon snail started attacking another moon snail, but only managed to get the job halfway done before the prey moon snail escaped. [1]

To be fair, moon snails aren’t just vicious cannibals – they also enjoy the snail equivalent of a nice salad. Another study that analyzed the tissues of moon snails revealed that their bodies have the chemical signatures of omnivores. The technique is called stable isotope analysis, wherein scientists use the ratio of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in an animal’s body to determine its diet, in broad terms. Carbon exists in three isotope forms, meaning the number of protons is the same in all three atoms, but the number of neutrons is different in each (carbon-12, carbon-13, and carbon-14); Nitrogen also has three isotope forms, nitrogen-14, nitrogen-15, and nitrogen-16. The vast majority of carbon on Earth is carbon-12, which is a stable isotope, as is carbon-13, meaning they do not decay over time; nitrogen-14 and -15 are stable, and make up the vast majority of nitrogen atoms. Different plants and animals have different ratios of carbon and nitrogen isotopes. The ratios of isotopes in plants and animals differ and these differences transfer to the body of the consumer, and so the isotope ratios of a meat-eating animal will differ from those of a vegetarian animal, and an omnivorous animal will be different again. Scientists were surprised to find that wild moon snail isotopes suggested they also ate non-animals, so to check their findings they fed captive moon snails nothing but clams, and then tested their isotopes – which looked exactly as one would expect in an all-meat diet. Apparently the wild moon snails were actually eating things other than meat, probably algae. This was a big deal, since so much of the literature on moon snails is about their predatory drilling! [2]

Moon snail shells are a relatively common find on east-coast beaches (and another moon snail, Euspira lewisii, is a common find on the west coast), but if you’re at the beach this summer, there’s more to look for than just shells – moon snails also leave behind very distinctive egg nests, often called “sand collars.” The fertilized female snail nestles into a little hole in the sand (as all moon snails do during the day when they’re not feeding) and produces a sheet of mucus, which she mixes with sand and pushes up to the surface, as she does so, the sheet curls around her shell and eventually right around to form a ring. This fusion of mucus and sand grains solidifies, she attaches her thousands of eggs to it, and then covers those with another layer of mucus and sand. Once the eggs are ready to hatch after a few weeks, when the next high tide comes along the eggs let go thousands of little larvae called veligers, which will drift off to finish developing into baby snails who will eventually settle into the intertidal zone and start lives for themselves. Once the eggs hatch, the collar becomes brittle and disintegrates, but if you find one that’s still plastic-y on the beach, leave it! There are thousands of tiny baby vicious predators in there waiting to hatch! Awww.

Sabrina Spiher Robinson is Collection Assistant for the Section of Mollusks and Tim Pearce is Head of the Section of Mollusks at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

References

[1] Gregory P. Dietl and Richard R. Alexander, Post-Miocene Shift in Stereotypic Naticid Predation on Confamilial Prey from the Mid-Atlantic Shelf: Coevolution with Dangerous Prey PALAIOS Vol. 15, No. 5 (Oct., 2000), pp. 414-429

[2] Casey MM, Fall LM and Dietl GP, You Are What You Eat: Stable Isotopic Evidence Indicates That the Naticid Gastropod Neverita duplicata Is an Omnivore. Front. Ecol. Evol. 4:125. (2016) doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00125

RELATED CONTENT

Oysters Swim Towards a Siren Soundscape

Slipper Snails Slide Between Sexes in Stacks

The Busyconidae Whelks, Homebodies of the East Coast

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Pearce, Timothy A.; Robinson, Sabrina SpiherPublication date: July 31, 2024