by Stevie Kennedy-Gold

Your online orders of clothes and household goods might well have shared shipping space alongside preserved toads and snakes from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Don’t worry though – museum specimens are shipped following long-established rules and regulations, and the movement of herpetological freight is all in the service of science.

Wait, what?! Well, at a relatively low, but steady rate, natural history museums loan out specimens, and these materials are generally shipped, outgoing and incoming, via regular commercial carriers.

Why loan out a specimen?! Why, to ask and answer awesome scientific questions, to enhance an exhibit, or to use as artistic references! Just as every human has a story unique to their own life and experiences, etched in their wrinkles, freckles, and scars, the same is true for every specimen in the collection. Each frog and lizard, snake and turtle has experienced different environmental impacts, endured famine, parasites, pollution, or predation. Each specimen has its own story. Instead of being written down within the pages of a book, the animals’ stories are recorded within their muscles, organs, bones, and DNA. As such, an eastern fence lizard collected from Pennsylvania in 1893 will likely have a different body size, diet, or parasite load compared to the same species of lizard collected from the same town in 2005.

Scientists request loans from museum collections so that they can examine the specimens, unlock the stories hidden in each body, and answer their scientific questions. Alternatively, we receive requests from artists needing reference materials for their newest works of art, or to more accurately render images of a species they would otherwise not be able to see up close (I’m looking at you, venomous snakes, highly toxic frogs, or now extinct species!). And, of course, museums themselves loan from collections to use in displays as representatives of the far larger number of specimens housed behind-the-scenes. Walk through Dinosaurs in their Time towards Cenozoic – those bones can be considered as an inter-building loan from our Vertebrate Paleontology collection. Head up to the Foster Overlook and check out our hellbender who choked on a marshmallow – that specimen is certainly an inter-building loan from the collection I manage.

But how exactly are specimen loans arranged? The process varies from institution to institution and from section to section, so this description is the process specific to the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at this museum. Overall, though, the process is a great deal easier than it would seem. Assuming a borrower knows what species to work with, a search of the Section’s online presence at iDigBio or VertNet will determine the specific specimens to request. After that, a formal request letter is required. This document must include details of borrower affiliation, the species and specimens requested, and the reason behind the request along with any planned examination techniques. The next step in the procedure is an email directed to me through the museum website (here), again providing a brief description of the borrower’s intent.

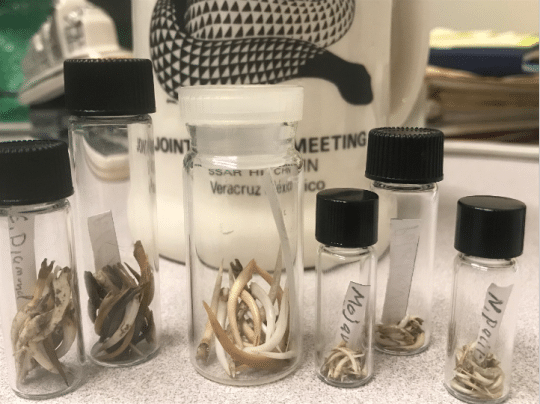

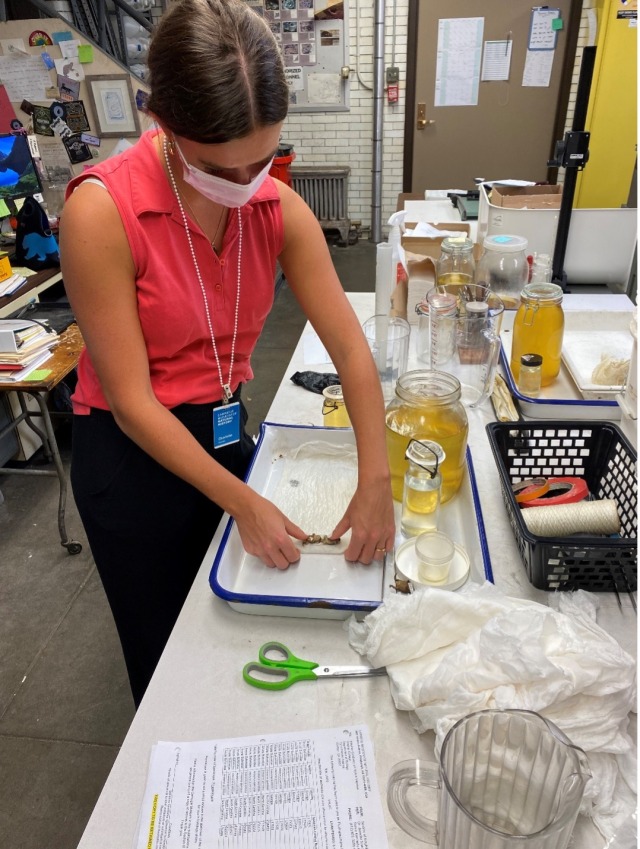

Assuming a request is reasonable (i.e., doesn’t involve the complete destruction of the specimen!), I then begin pulling the requested specimens from the collection, placing tiny loan slips in each jar as I go as place holders signifying the specimen’s loaned status (Image 1). The slip has the specimen’s catalog number, the loan number, and the requester. Paper trails are vital in loaning specimens. I also make a notation in my fancy new Loan database, as well as in the general Herp Section Specimen database. Finally, I draft up the loan contract which will be sent out with the specimens. I then wrap the specimens in cheesecloth (Images 2 and 3), give them a good soaking in alcohol, triple bag and heat seal them in, and slap the appropriate documentation on and in the box. The package then goes off to the mailroom!

Once someone has completed their work with the specimens, they normally notify me and ship the specimens back as soon as possible. Assuming all the specimens are returned in good order, the loan is closed, the specimens are returned to the collection, the slips of paper are pulled from the jars, and the specimens once again become available for other people to use.

Unfortunately, some specimen loans, like library books, become overdue. A typical loan duration is 6 months, at the end of which the borrower can request a loan extension (much like requesting an extension on a library book) or they can send the specimens back. If the loan period elapses without any communication, I don my imaginary “Lizard Librarian” hat and kindly request their return as soon as possible.

Due to the size of this collection, the responsibilities of a collection manager, the number of loans we send out annually (some years over 40!), and the recent (with respect to the general age of the collection) technological adoptions within the Section (i.e., creating digital databases), it is not surprising that the retrieval of some loans lapsed, and even the documentation of some specimen locations is unclear. As a result, I recently took it upon myself, with the aid of my fearless and tireless group of interns, work study students, and volunteers, to determine the “active status” for all loans sent out since 1925 (the earliest recorded loan in the section). We have nearly 2000 loan records to look through, but fortunately my predecessors did a decent job tracking when a loan was returned or when contact was made to request the specimens be returned.

It’s a long arduous process making sure that all the specimens are back. Initially, our search to verify if the specimen was returned begins with the jars containing species from the location where the borrowed specimen was collected. This process takes time, and the pace is contingent upon how many specimens were requested per loan and how many specimens (and jars!) of a specific species from a specific place we have in the collection. For example, tracking the whereabouts of a loan of 50 eastern newts from Pennsylvania has taken us a few weeks because we have nearly 20 jars of newts from the state, each containing at least 100 specimens.

If we emerge empty handed after examining all the jars of a specific species from a specific place, we then look in jars containing the same species collected from other locations. This process has resulted in finding almost 10 specimens previously deemed “missing” – some since the 1960s! On top of this process, we also record the catalogue number of every specimen in every jar we examine so we can update the jar labels with the specimen numbers (Image 4). This expedites finding specific specimens in the future and ensures that all specimens are placed in their correct jars. It’s a true labor of love and the process is a museum collection equivalent of an (ultra-ULTRA) marathon, not a sprint. When it all boils down though, I am just a librarian making sure that all my books (or specimens!) are where they ought to be.

Stevie Kennedy-Gold is the Collection Manager for the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Digital Developments: Why Archiving and Herpetology Go Hand-in-Hand

Do Snakes Believe in the Tooth Fairy?

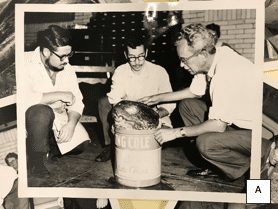

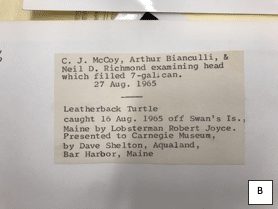

A Head Above the Rest: Unearthing the Story of Our Leatherback Sea Turtle