If you had told me when I was 15 that I would spend my life as an archaeologist, I probably would have been pretty surprised. I didn’t grow up knowing a great deal about archaeology or even being fascinated by arrowheads. At that time, I might well have asked what an archaeologist really is and what one actually does. I did get to visit the Parthenon and other ruins while on a trip with my aunt when I was sixteen. Even then, I don’t remember having more than a casual interest in what could be learned from these places. I was more interested in the living people and the new food dishes I encountered on that trip, which was my first trip outside the United States.

From talking to other archaeologists, I’ve learned that there are a lot of paths to deciding archaeology is going to be your life’s work. In my case, what led me to archaeology was anthropology, and specifically an elective course I took in the Fall of my senior year in high school that was taught by a Ph.D. student at the University of Massachusetts. Until then I had not been a serious student, although I did well enough in school. Perhaps I was slightly bored by most of my courses, but anthropology was anything but boring! It looked at people elsewhere in the world and over great periods of time. Many of these people lived different lives than my friends and I did, and they sometimes thought very differently about what was important in life than people here in the United States. I was fascinated, and, honestly, I particularly liked the fact that the conventions of American society, which to my teenage self were sometimes a little confining, weren’t after all the only sensible way to approach life. That year, as I chose a college to attend, I specifically looked for anthropology programs. I chose Beloit College in Wisconsin, which to this day has an excellent anthropology program.

Initially, I thought that I was most interested in cultural anthropology, but like most anthropology departments in the United States, Beloit required its anthropology majors to take courses in biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and archaeology as well as cultural anthropology. These are what are known as the four fields of American anthropology and together, they give us a more complete picture of humans in both the past and the present. Most people focus their careers in one subfield or another, though we recognize the importance of each one for understanding humans, and in most cases in North America our degrees are in anthropology not one of the subfields. In college, I found all these courses more fascinating than anything I had studied before, and I actually became a good student as I explored anthropology. I was learning so much neat stuff! I also did volunteer work in the Logan Museum at Beloit, which was founded at the end of the nineteenth century and holds some pretty amazing ethnographic and archaeological collections. It was there I first became interested in artifacts and learned to clean and care for them. After a college internship in cultural anthropology convinced me that cultural anthropology was not the most interesting part of anthropology after all, I began to focus on archaeology. I was most intrigued by my courses in Mesoamerican archaeology and North American archaeology, which before college had been completely unknown to me.

When I graduated from college, I still wasn’t sure what I would do with my life. I worked for about two years both in social work and as a tax auditor for the IRS, but decided in 1974 to try graduate school in archaeology because I still found what archaeology had taught me about past people compelling. I lived in Chicago, so I enrolled in the Ph.D. program in North American archaeology at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

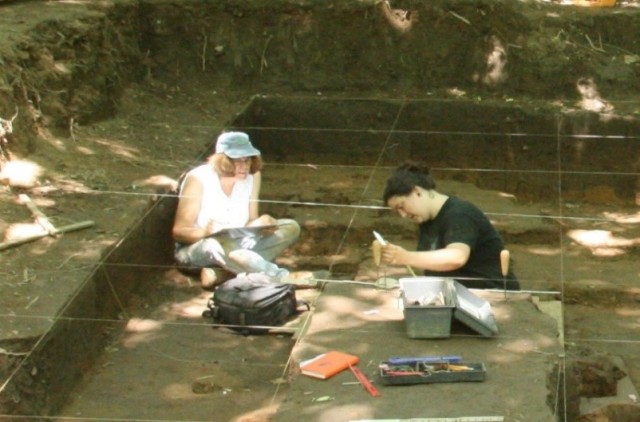

The biggest shock of graduate school was my professors’ almost immediate insistence that I pick what research I wanted to do. They pushed me to develop an expertise or skill within North American archaeology through my research. It sounds obvious to me now, but I think many beginning graduate students are like I was, lovers of the discipline’s knowledge, but a bit daunted by becoming an independent researcher. Developing an area of focus and specialty skills is part of becoming a professional archaeologist. One reason for this is because contemporary archaeological undertakings rely on teams of researchers, each contributing special skills and knowledge to accomplish the many aspects of excavation, analysis, and interpretation. If you envision archaeology as the solitary pursuit of an elusive artifact or site, you don’t have the picture quite right. Think instead of archaeological fieldwork involving groups of scientists working together to discover and carefully record many different bits of evidence about what the world used to be like and what people did in it. Also think about the many hours these scientists and others will spend not only in the field, but in the laboratory after an excavation is completed cleaning finds, describing artifacts, and analyzing data in order to make meaningful interpretations.

For someone like myself, who loved all aspects of anthropology, not to mention archaeology, and who had only gradually settled on North America as my geographic focus, picking a focus on entering graduate school was a hard task. There was so much that would be interesting to study! However, I did remember especially enjoying a research paper I had done in college on the relatively new interdisciplinary field of zooarchaeology, so under pressure, I told my professors I wanted to pursue this subfield in graduate school. Amazingly, this turned out to be a good choice of specialization for me. I found that I really love to work with collections of animal bone. For me, opening a bag of bone refuse from a site still is exciting. Bone identification work is a little like doing a jigsaw puzzle without all the pieces. It is challenging, and it takes concentration and careful observation to piece together what you can. There is so much to figure out about any single piece of bone! What animal is it? How healthy was the animal? What part of the animal’s body is it? Has it been burned or cut? How was the bone buried and changed after the humans were done with it? Then you have to record this information so it can be combined with other observations on the assemblage of bone you are looking at. After identification, making sense of what a collection of the bones means and correlating these kinds of data with other information from a site and region requires careful analysis, but also insight and creativity. To me it is endlessly fascinating.

Besides finding that I liked the work, choosing zooarchaeology was also serendipitous since my professors were looking for a student to work with them on this aspect of a big project they were undertaking in west-central Illinois centered on the Koster site, which was first inhabited more than 9000 years ago and then reinhabited by people right up into modern times. Most importantly the poorly known Archaic Period levels were numerous, well-preserved, and distinct from each other so we could add a lot of new information through our work. For my dissertation I was able to look at the animal remains from levels of this site dated between approximately 8500 and 6000 years ago, which represent how people used animals at that time.

Graduate school was intense, but I continued to be fascinated by archaeology’s ability to tell the story of people lost to standard Western history. In those days I was excited to be part of this science that could do so much more than describe and take care of cool artifacts. It was a heady thing to learn that I could contribute to what was known about people who lived thousands of years ago. In later years, I’ve had to think more critically than I did then about what a privilege it is for an archaeologist to learn about the history and lives of other ethnicities. Today’s archaeologists recognize their responsibility to present information about past people for both scholarly and public use in ways that are sensitive to what is considered sacred and private by the descendants of those people. I think this is an important change in perspective, but in the 1970s most archaeologists just wanted to show that people’s stories from the past could be told using the techniques of archaeology. I certainly was happy, if a little naively so, to have found a way to contribute to telling the human story.

If I consider entering graduate school as the start of my professional career as an archaeologist, I have been pursuing this career for more than 45 years! Over the years I have done zooarchaeological and archaeological work in the American Midwest, Southwest, Southeast, and Northeast working on telling the story of people who lived as long as 9000 years ago and as recently as the Sixteenth century. I’ve worked at several universities, in a small museum, and on small and large archaeological projects in the field of Cultural Resource Management (CRM) doing archaeological survey, site excavation, and zooarchaeological identification and analysis. I’ve written scholarly papers and articles as well as a textbook on North American archaeology. However, beginning in the late 1980s, I spent more than 31 years doing research and teaching anthropology and archaeology here in Pennsylvania at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. In this job I taught both undergraduates and graduate students, but, as is typical of university professors, I also spent time doing fieldwork and analysis as part of my research while at IUP. Fortunately, because archaeology is a team undertaking, I’ve been able to involve many students in my research. Working with students in research as they discover what fascinates them has been a highlight of being an archaeologist for me. I’ve now retired from teaching but not archaeology. I’m still working with both physical and digital archaeological collections both through CMNH and elsewhere and writing about archaeology. Who knows what this career still will bring me!

If you are reading this blog because you are thinking about archaeology as either a career or a hobby, I hope you realize that mine is just one story among the many that could be told. Because there are so many aspects of archaeology, people come into it from all sorts of backgrounds and because of all sorts of interests. I think that it is important to remember though that it really is about understanding people and telling their stories through the artifacts and other evidence we find. This is what interested me in archaeology in the first place. Discovering the details of the human story is a giant undertaking. There is no shortage of research problems or work to do, but solving the puzzles presented by sites and collections is both challenging and fun. I’m certainly glad I decided to become an archaeologist and zooarchaeologist so many years ago!

Sarah W. Neusius is a Research Associate in the Section of Anthropology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Professor Emeritus, Department of Anthropology, Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Definitions of Bolded Terms

anthropology -the study of humans including the physical, cultural and social aspects in the past and present.

cultural anthropology – the study of the cultural aspects of humans especially recent and contemporary social, technological, and ideological behavior observed among living people.

biological anthropology – the study of the biological or physical aspects of humans, including human biological evolution and past and present biological diversity.

linguistic anthropology – the study of the structure , history, and diversity of human languages as well as of the relationship between language and other aspects of culture.

archaeology – the study of past human behavior and culture through the analysis of material remains.

ethnographic – relating to the scientific description of people and cultures especially customs and beliefs.

Mesoamerican archaeology – the archaeology of the area from central Mexico southward through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica.

North American archaeology – the archaeology of the area from central Mexico northward throughout the United States and Canada.

zooarchaeology – a subarea of archaeology involves the identification of animal remains from archaeological sites and investigates the ecology and cultural uses of the animals represented.

assemblage -a collection of artifacts from the same archaeological context.

Archaic Period – a time period from approximately 10,000 BP to 3000 BP that is recognized in most of North America.

Cultural Resource Management (CRM) – an applied form of archaeology undertaken in response to laws that require archaeological investigations.

archaeological survey – the systematic process archaeologists use to locate, identify, and record archaeological site distribution on the landscape.

Related Content

Pennsylvania Archaeology and You