by Vanessa Verdecia

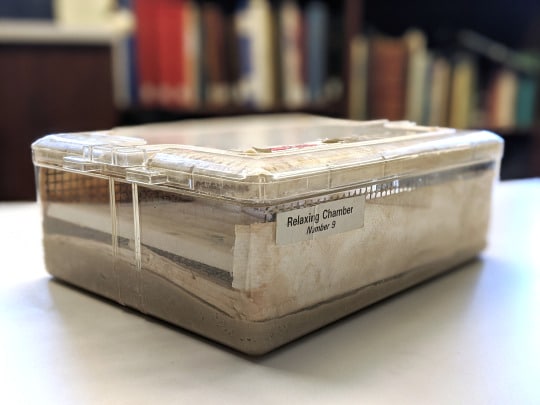

“Why do you collect so many?” That’s a common question we get from people who experience a glimpse into the Invertebrate Zoology collection at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The Invertebrate Zoology collection, which consists of mostly insects, but also includes crayfish, spiders, and other invertebrates like millipedes and centipedes, is the largest collection at CMNH.

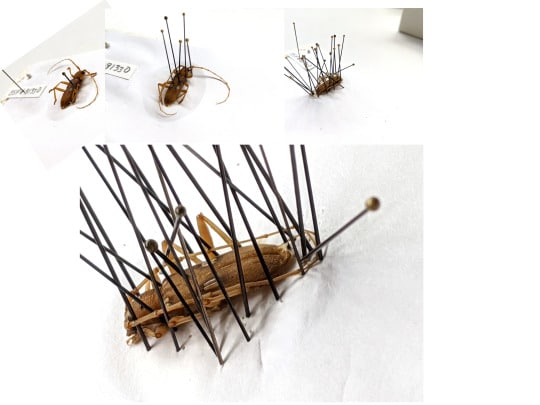

There are several reasons why we collect so many specimens. Nature is not always easy to interpret, even for the most knowledgeable scientists. In fact, an expert’s knowledge develops in part from time spent looking at many specimens, an unparalleled experience which helps create an accurate understanding of complicated species. So, one of the reasons we collect so many is to have enough material to look at and make informed decisions regarding species determinations. Some species can have significant variations across individuals. Having a lot of material also allows scientists to sacrifice some specimens for dissections or for use in molecular studies.

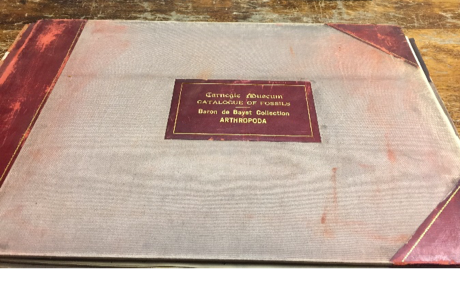

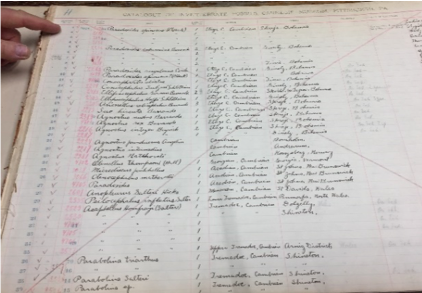

Another important reason for collecting so many is to create records of species occurring across as many geographical regions as possible and at different times of the year. By sampling and re-sampling, there is more data available to be analyzed and used to arrive at stronger conclusions. Having a historical collection is important for research that looks at species composition over time. Such collections help to answer questions about how biodiversity has been affected by climate change and other factors over time.

Collections as Scientific Tools

For these reasons, the insect collection at the Carnegie is an incredible scientific tool. We get many requests to borrow specimens, requests to visit the collection to gather data from the specimens, and requests for images of published specimens that are designated as types and deposited at CMNH. Type specimens are among the most scientifically valuable specimens, and the Invertebrate Zoology collection holds tens of thousands of specimens in type series that are referenced in scientific research and provide comparison material during the discovery of new species.

This background information leads to a nice little story for me to share. Sometimes requests for collection access come with a very special “thank you.” A request for images of type specimens in the Sphingidae (hawkmoths) collection earlier this year led to a publication that included new species, and instead of the usual acknowledgment, one of the authors named a new species after me—Marumba verdeciae. This type of taxonomic work, which involves making detailed observations related to the form and structures on the new specimens, requires the use of published museum specimens for comparative reference. Without access to the types, researchers would not be able to verify their discoveries, since comparison to the type material is essential in confirming the new species.

Naming Species

Biological species are given a Latin name in the form of a genus and species. Placement of a species in a given genus is based on a biological relationship, but the species name is unique. There should be a section in the published work that explains the root of the name, which is often based on a Latin descriptive term related to a distinct feature of the species. However, sometimes a new species is dedicated to a person. In the case of Marumba verdeciae, the genus (Marumba) already existed, and one of the new species was dedicated to me as recognition of the effort I put into locating and imaging type specimens needed as a reference for the research the authors were doing with this group of moths. People might have a species dedicated to them for various reasons, which range from participating in or facilitating the research, to achieving prominence as an expert in a group of organisms. The species name verdeciae is a Latin conjugation of my last name, Verdecia.

The focus of this story, however, should be the importance of CMNH collections, and other museum collections across the world. In this case, the researchers in Germany needed to reference type specimens deposited at CMNH in order to complete their research. But CMNH scientists also need to borrow and request images of type specimens deposited at other museums when doing their research. Strong collaboration between scientists is very important. As stewards of our collections, we are not only maintaining the specimens for our use, but for use by the entire scientific community.

Although it is an honor to have a new species named after me, the next step is the most exciting—the ongoing use of the new published work to hunt for specimens of the newly described species in our own collection. We have a vast collection in Invertebrate Zoology, and the moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera) comprise about 2/3 of the entire collection. There are many drawers with specimens that are not curated and there are over 100 drawers of mixed Sphingidae that, depending upon the geographical represented, might include some of the new species of Marumba. When new research like this is published, it allows curatorial staff to go into their collections to curate specimens, and update identifications. The Invertebrate Zoology collection is a work in progress, with many specimens waiting to be curated, and many discoveries yet to be made.

Vanessa Verdecia is Scientific Preparator in the museum’s Invertebrate Zoology Section. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

How to Prepare Insect Specimens

Ask a Scientist: What is a caterpillar database?

Garden for the Birds (or bees, or butterflies, or creepy crawlies, or you get the picture)…

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Verdecia, VanessaPublication date: May 10, 2021