by Patrick McShea

Fish in the wild are difficult to observe, even for the scientists who study them. Monster Fish: In Search of the Last River Giants, an exhibition traveled and developed by the National Geographic Society, encourages visitors to learn about this challenge from one such scientist, Dr. Zeb Hogan, host of the popular Nat Geo Wild television show.

In the exhibition, now on view in the R. P. Simmons Family Gallery until April 10, 2022, stunning life-size sculptures, evocative illustrations, and informative panels set the stage for Hogan’s appearance on several well-spaced video screens. Here, in clips with run times of a few minutes, Hogan presents on-the-water, and sometimes in-the-water, reports from six continents about conservation efforts that involve not only other scientists, but also the local people who rely on healthy fish populations for their food or livelihood.

Observing Fish in the Wild

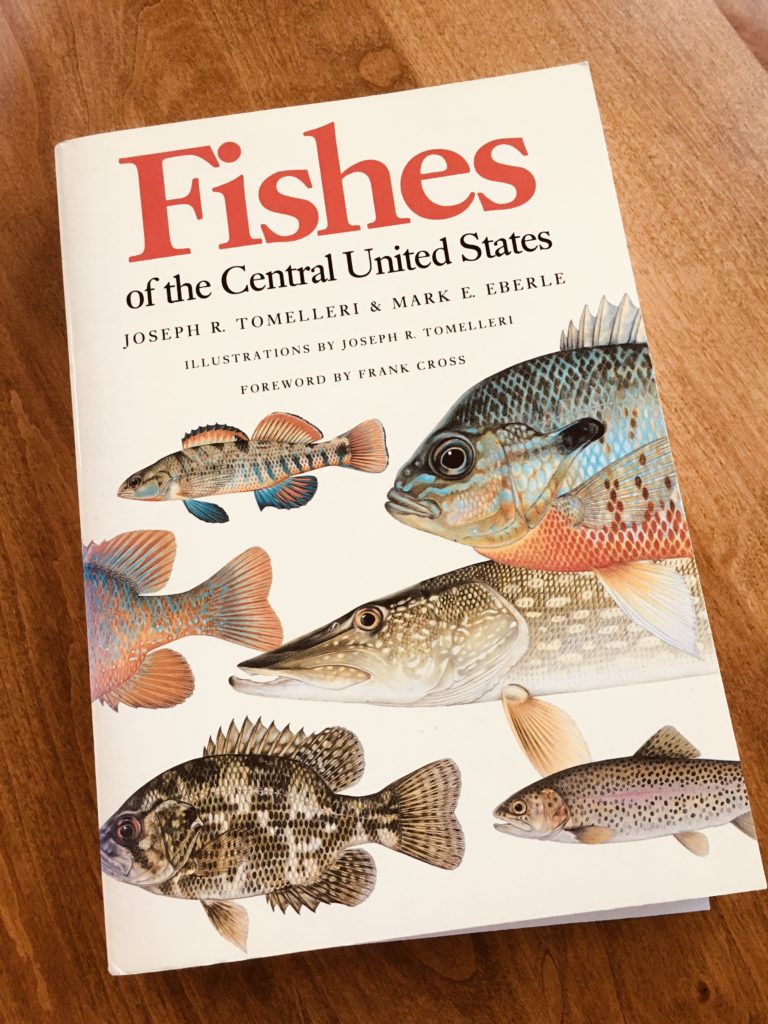

Away from the exhibition, the importance of images in sparking an interest in hard-to-observe wildlife can be noted at a scale where both the creatures involved, and the extravagance of their depictions, are much reduced. By personal example, much of my visual understanding of lesser known fish species in Pittsburgh’s rivers comes from viewing the scientifically accurate, full color, plates in Fishes of the Central United States (University Press of Kansas, 1990), a book illustrated and co-authored by Joseph R. Tomelleri.

Over the past 36 years, the artist’s detailed portraits of our continent’s finned wildlife have appeared in over a thousand publications ranging from fishing magazines and field guides to outdoor clothing catalogues. Tomelleri’s career as fish artist began in Kansas in 1983 when he and other biology graduate students at Fort Hays State University wondered about the diversity of fish species in a stream that winds through the campus. The resulting student-driven investigation culminated in a publication titled, Big Creek and its Fishes, a work in which Tomelleri had responsibility for fish images. Because the full suite of physical characters that distinguish one fish species from another can rarely be captured in photographs, he used colored pencils in an attempt to accurately render every scale and fin ray.

As the artist’s attention to anatomical detail led to a professional career, his illustration process became standardized. Subjects are collected by seining, through the electrofishing techniques used by fish biologists, or by old-fashioned angling with rod and reel. A captured fish is immediately photographed to record natural colors, then depending upon size, preserved frozen or in a formalin solution that is later replaced with an ethanol solution.

Although Tomelleri says the physical requirements for preservation have limited his experience with “monsters” to creatures three feet long or less, one species account in Fishes of the Central United States makes a case for the frightening aspects of fish that size. A description of Flathead Catfish, a species that recently brought attention to Pittsburgh’s rivers because of the enormous specimens caught and released by local anglers, includes a cautionary warning:

Flatheads breed in natural cavities of river banks, an instinct that leaves them susceptible to illegal hand fishing or “noodling.” Adept noodlers can recognize a big cat’s den by feeling the cleanly swept cavity floor and mound of silt or debris in front of the hole. One may assume that it is the bone-crushing bite of a 60-pound flathead that keeps the slightly squeamish stuck on the bank with rod and reel.

Patrick McShea is an Educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Preserving Fossil Treasures: Eocene Fishes from Monte Bolca, Italy

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: March 31, 2022