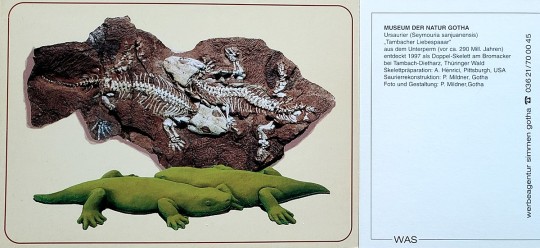

At lunchtime on the last day of the 1997 field season, Thomas Martens discovered the two exquiste specimens shown above, the only fossils found that year. Thomas had uncovered a piece of the hip region with some attached vertebrae that resembled, once again, those of the ancient amphibian Seymouria. Because our work time was limited, we estimated the length of the specimen and rushed to extract it from the quarry. When we flipped the block over, a few pieces of rock fell out, revealing a series of vertebrae of a second individual in the block. We were thrilled to learn that Thomas had discovered two specimens of Seymouria. We put the rock pieces back in place and quickly finished plastering the block. There was just enough time for Dave, Stuart Sumida, and I to return to our hotel, clean up, quickly pack, and meet Thomas, his family, and his fossil preparator Georg Sommer for a celebratory dinner. What a great way to end the field season.

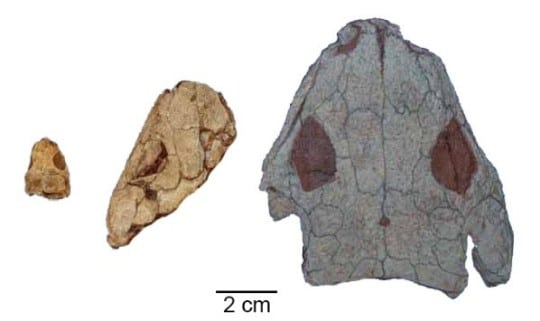

Seymouria had already been known from the Bromacker quarry. Thomas had discovered and identified two skulls in 1985, fossils he brought with him when he came to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) in 1993 to study for six months with Dave Berman under a CMNH-financed fellowship. Both skulls were of juvenile individuals. Of the two known species of Seymouria, Dave and Thomas were excited to discover that the Bromacker skulls were nearly identical to those of Seymouria sanjuanensis. The 1997 lunchtime discovery of the two complete adult specimens confirmed the identification of the Bromacker Seymouria as S. sanjuanensis.

The first discovered species of Seymouria was Seymouria baylorensis, from near Seymour, Baylor County, Texas, from which its name was derived. Seymouria sanjuanensis was first found in San Juan County, Utah, by Dave Berman and the field team he was leading as a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dave’s advisor, Dr. Peter Vaughn, named it Seymouria sanjuanensis in reference to the county of discovery. Another discovery of five specimens of this species preserved together was made by Dave in New Mexico in 1982.

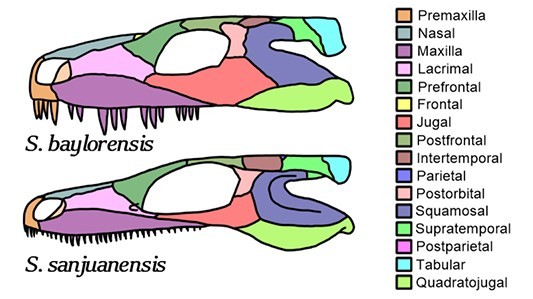

Seymouria baylorensis is geologically younger than S. sanjuanensis and has a more robust skull, larger and fewer teeth of variable size, and a subrectangular postorbital bone compared to the chevron-shaped postorbital of S. sanjuanensis.

Seymouria is considered a terrestrial amphibian that only returned to water to breed. Its strongly built skeleton provided the support needed to move on land. With its numerous, slender, pointed teeth, S. sanjuanensis most likely ate insects and small land-living vertebrates. We know that the Bromacker Seymouria didn’t consume fish, because not a single fish fossil, scrap of fish fossil, or fish coprolite (fossil poop) has ever been found at the Bromacker quarry. Study of the rock deposits preserving the fossils at the Bromacker indicate a lack of permanent water, which would explain the absence of fish.

Conditions for breeding must have been favorable in the Tambach Basin, the ancient basin where sediments preserving the Bromacker fossils accumulated, because several juvenile specimens of Seymouria are known. The smallest is a skull measuring about ¾ of an inch long. In a study led by our colleague Josef Klembara (Comenius University, Slovak Republic), we determined that the smallest individual was post-metamorphic—in other words, no longer a tadpole—based on the presence of certain ossified bones in the skull. In tadpoles, these skull elements are cartilaginous; that is, they haven’t yet turned to bone.

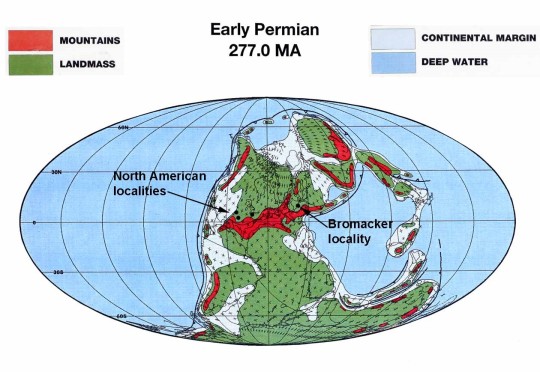

The discovery in Germany of the same species of Seymouria previously known only from New Mexico and Utah has important implications in terms of paleobiogeography (the study of the distribution of species in space and time). At the time S. sanjuanensis was alive, the continents were merged to form the supercontinent Pangaea. The presence of S. sanjuanensis across Pangaea, north of a roughly east-west trending mountain range, indicates that climatic or physical barriers (e.g., deserts, inland seas, mountain ranges) didn’t prevent its dispersal.

The two Seymouria specimens preserved together were a big hit in the local region in Germany. Museum der Natur (MNG) exhibit preparator Peter Mildner nicknamed them the “Tambacher Liebespaar” (“Tambach Lovers”) after a painting entitled “Gothaer Liebespaar” (“Gotha Lovers”) on exhibit in the Herzogliches Museum of the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein (also the parent organization of MNG). This name caught on and is fondly used by our German friends and colleagues. Peter even made a fleshed-out model of the two Seymouria specimens in their death pose. The proprietor of the hotel in which we stayed hung a copy of the model of the Tambach Lovers and a framed collage of newspaper articles featuring the Bromacker on a wall in one of the hotel rooms, which she named the “Präparation Suite” (i.e. “Preparation Suite” in reference to the preparation of fossils). I often stayed in this room.

A cast of the Tambach Lovers specimen and a model of Seymouria sanjuanensis are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for them once the museum re-opens. And stay tuned for my next post, which will feature the unusual bipedal reptile Eudibamus cursoris.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Seymouria sanjuanensis, here is a link to the publication describing the 1997 specimens: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020%5B0253%3AROSSSF%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Keep Reading

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part VII: Eudibamus cursoris, the Original Two-legged Runner