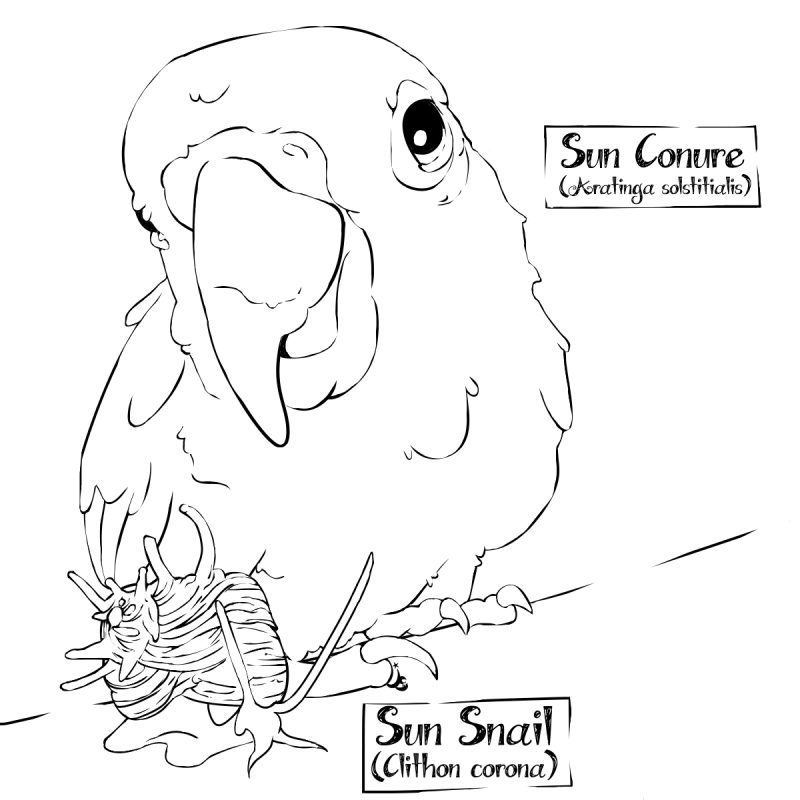

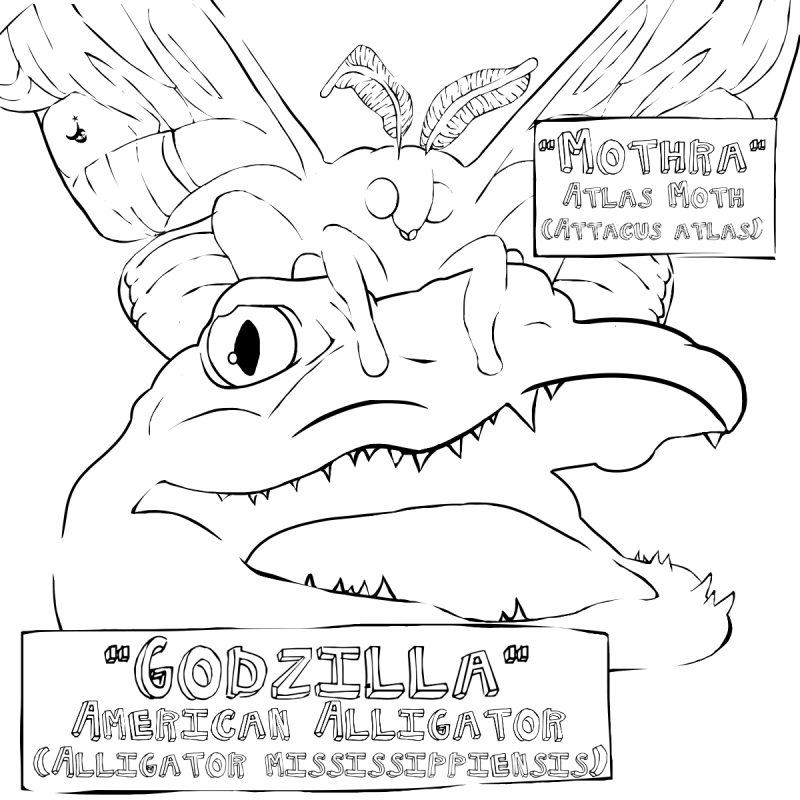

Have fun coloring images featuring animals from our living collection this week drawn by Gallery Presenter and Floor Captain, Jess Sperdute. You can meet some of the animals in the living collection during our Virtual Live Animal Encounters!

Super Science Saturday

Super Science Coloring Pages!

Have fun coloring images featuring animals from our living collection this week drawn by Gallery Presenter and Floor Captain, Jess Sperdute. You can meet some of the animals in the living collection during our Virtual Live Animal Encounters!

Super Science Activity: Paper Flowers

Spring is here, and the flowers are blooming! Not all flowers bloom at the same time, but with these instructions and a few supplies, you can make your own beautiful paper bouquet of spring flowers that will last all year. Plus, learn a few facts about their living counterparts and why plants are more interesting than you might think with Mason Heberling, assistant curator and Sarah Williams, curatorial assistant in the Section of Botany at the museum! *This activity requires a grown-up!

Before we start, let’s talk about spring flowers!

Many plants that go dormant in the winter, or stop growth, like hibernation for plants respond to certain cues so that they emerge and bloom at the “right” time. These cues include spring temperatures, length of daylight, known as photoperiod, and a set length of cold period (known as vernalization or “winter chilling”). It’s complicated and we are still learning how different species respond differently to each of these cues.

Like many spring flowers, both in your gardens and in the woods, the plants we are making today have big belowground structures called bulbs. Perennial plants with bulbs are known as geophytes (“geo” meaning earth and “phyte” meaning plant), these belowground bulbs come in many forms but serve as storage for energy (sugars) and water. Many geophytes can live many years and because their bulbs are protected belowground, have evolved to withstand many stresses, including fire, extreme temperatures, lack of water, and more. When the soil warms, sometimes even the slightest amount, in the spring, these belowground bulbs fill with water, cells expand, and out of the ground comes the beautiful flower! These flowers are not only beautiful to us—they signal to attract insects and wake up the web of life in our region.

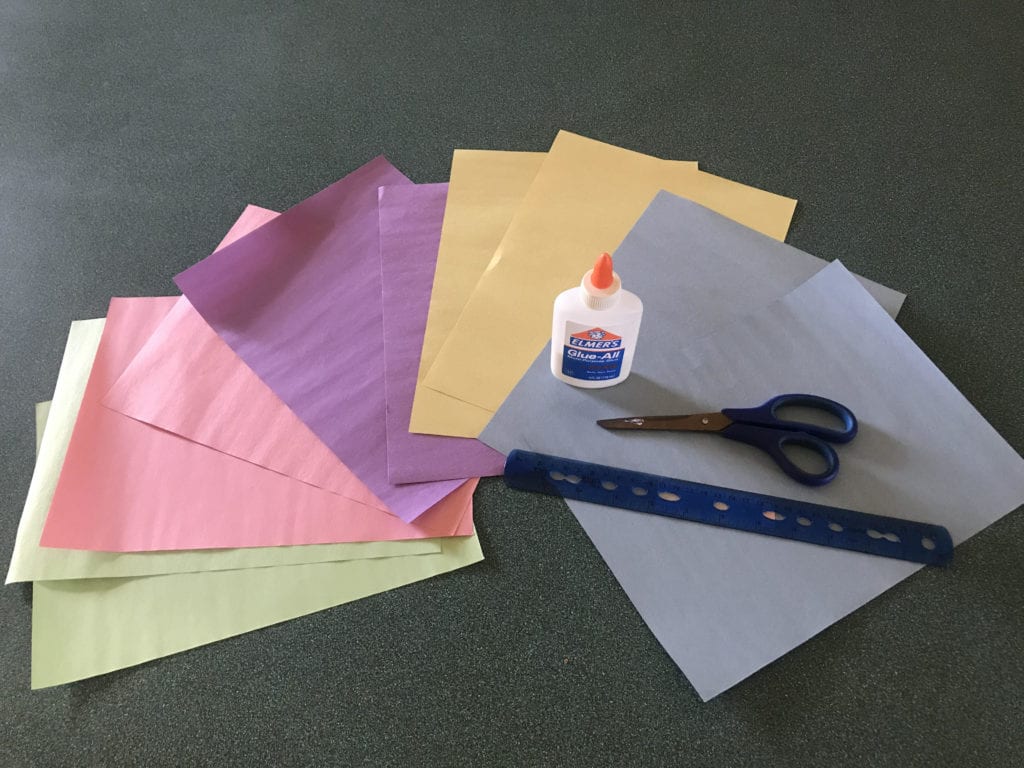

What You’ll Need

- Colored construction paper or card stock (make sure to have green paper for the stems!)

- Scissors

- Pencil

- A small surface to roll paper (this project used the end of a paintbrush)

- A ruler

- Glue

- *OPTIONAL* Green Pipe Cleaners for stems instead of green paper

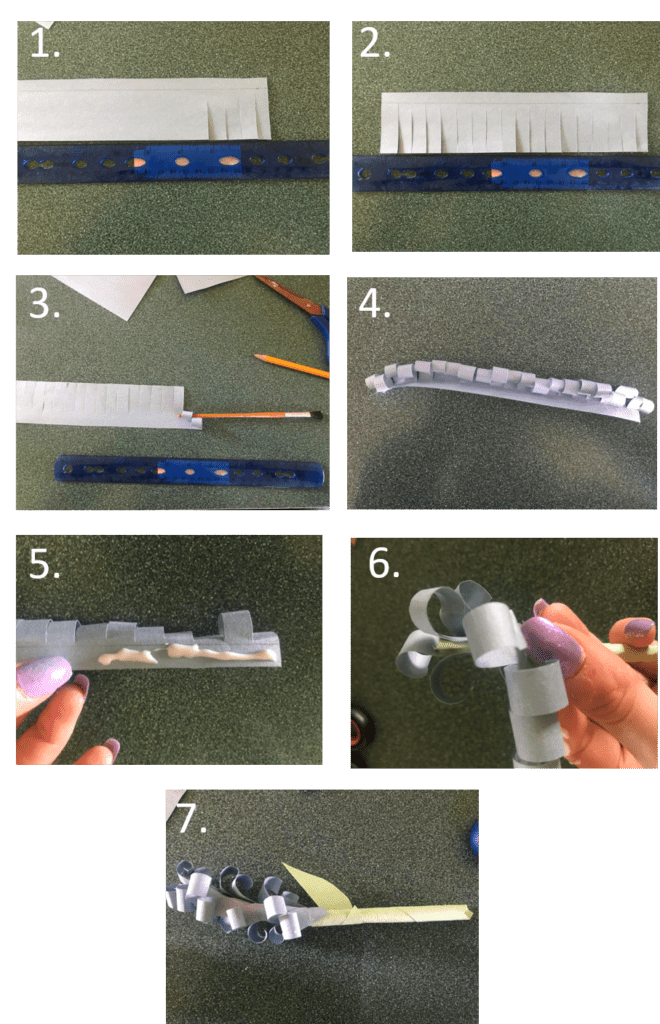

How to Make a Paper Hyacinth

- Measure and cut a 9×2 (or, if you are using cardstock, 8/8.5×2) rectangle from your colored paper (this is for the flower portion, please see the directions below on how to make stems and leaves. Measure out 3/8’’ from the bottom of your 9×2 rectangle and draw a line across the entire length of one side. Cut out small rectangles roughly 1/4’’ in size (these don’t need to be accurately measured and look more natural when a little different in sizes!), stopping before the pencil line at the top of the rectangle.

- Repeat your cuts across the length of the entire rectangle. Flip your rectangle over to hide the pencil marks.

- Using a small surface to roll your paper (like a pencil), roll each strip tightly (it’s ok if they loosen at any point during construction, just make sure they’re still rolled a little).

- Flip your rolled-up strips so that your pencil marks from earlier are facing up

- Glue along the bottom of the rectangle

- Make a paper stem and some leaves, or use green pipe cleaners. Holding your stem and your rolled-up strips, begin by placing the end of the roll to the top of the stem and slowly work your way down by spinning the stem (this may take several minutes—just go slowly and hold your roll to the stem for a few seconds until it has a chance to stick!). Continue down until the end of the roll

- Wait for the glue to fully dry before adding leaves

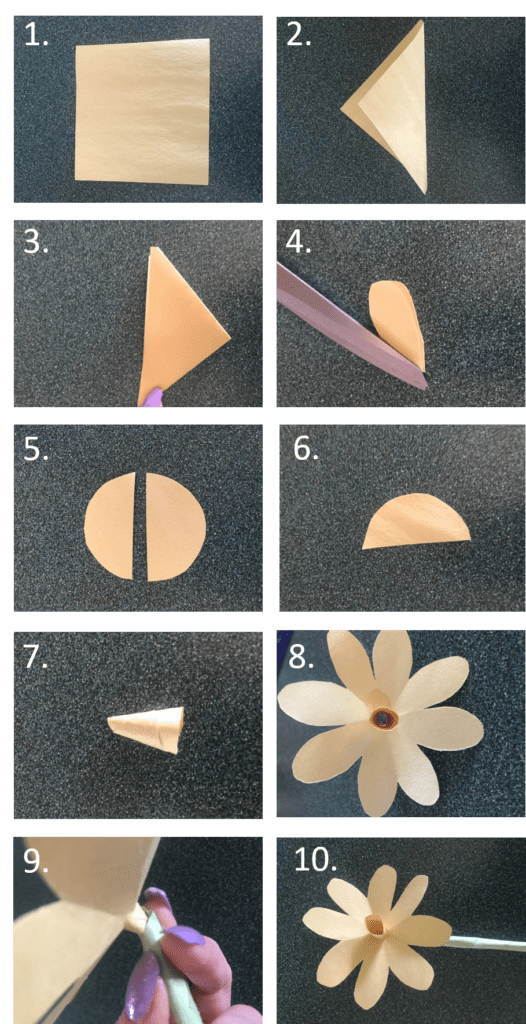

How to Make a Paper Daffodil

- Cut out a 4×4 square from your paper

- Fold your paper diagonally to make a triangle.

- Fold your paper in half two more times to make a smaller triangle.

- Cut a petal shape from the end of the outer corner of you triangle to the inner corner where all of the folds meet. Cut off the tip of the inner corner of your triangle.

- Cut a circle out of your paper (size doesn’t matter, but don’t make it too small!).

- Cut your circle in half.

- Using one half of your circle, fold it into a cone.

- Unfold your petal shape from step 4—it should look like a flower with a hold in the center (if it doesn’t, repeat the first steps and cut the petal shape from the opposite direction). Glue your cone from step 7 into the middle of the flower and hold it in place until the glue dries.

- Gently push your cone through the center of the daffodil and glue where the sides of the cone meet the petals.

- Create a stem (or use pipe cleaners), and glue the end of the stem to your daffodil.

- Hold the daffodil in place for a few moments while the glue dries.

- Create a leaf or two and glue to your stem.

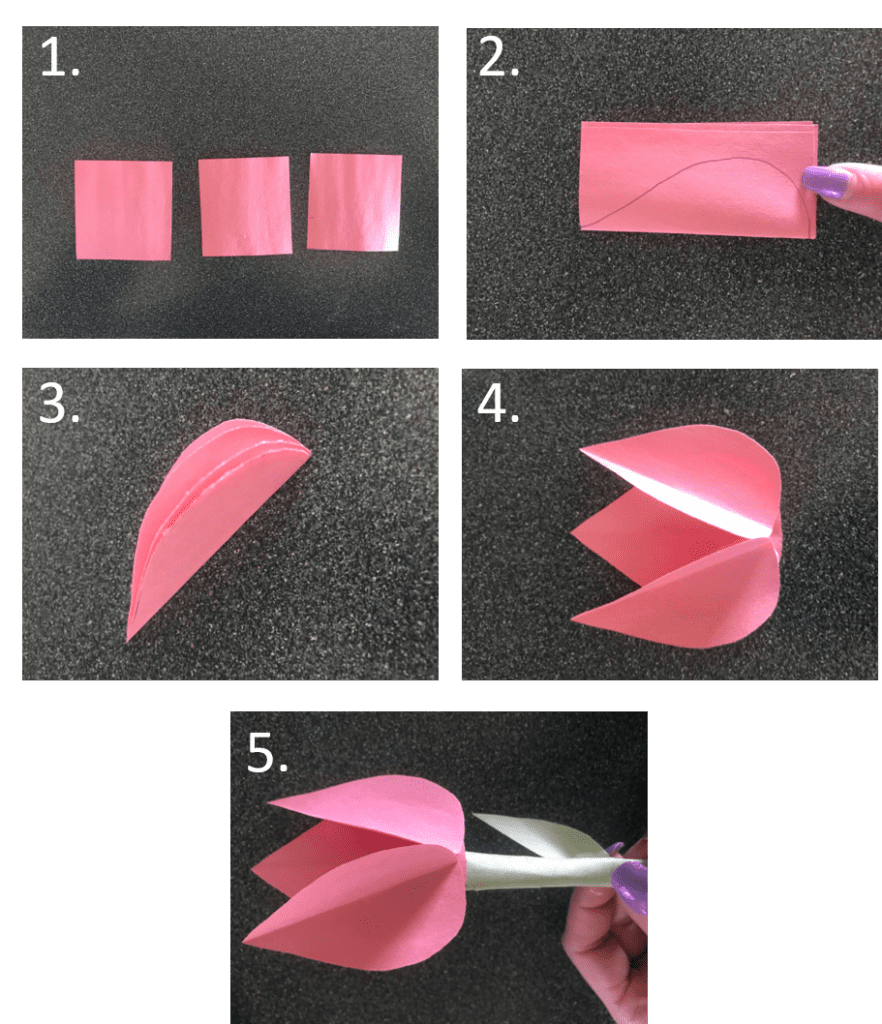

How to Make a Tulip

- Cut out three 3×3 sheets of paper. Stack the papers on top of each other and fold them in half.

- Draw a petal shape on the side of the fold.

- Cut out the petal shape using the pencil lines as a guide.

- Take one petal and glue both sides. Place the other two petals on either side of the glue. Hold down the petals gently until the glue dries.

- Create a stem (or use pipe cleaners), and glue the end of the stem to your tulip.

- Create a leaf or two and glue to your stem.

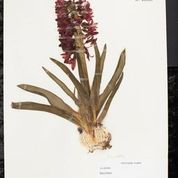

About Hyacinths

- Hyacinth has a single dense spike of fragrant flowers in shades of red, blue, white, orange, pink, violet or yellow

- Hyacinth bulbs are poisonous; they contain oxalic acid. Handling hyacinth bulbs can cause mild skin irritation. Protective gloves are recommended.

- Very fragrant, commonly used in perfume

- Though only including three species, Hyacinths have been grown in gardens and bred over the past centuries, with thousands of named varieties (known as “cultivars”)

- Wild hyacinths are native to Mediterranean and western Asia (including Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey) but are widely grown around the world.

About Daffodils

- Though known by human cultures long before and grown for many centuries, Carl Linnaeus formally described and named Narcissus in his famous book Species Plantarum in 1753. The genus was also described in the Flora of North America in part by former Carnegie Museum of Natural History Curator of Botany, Frederick H. Utech, who studied many species in the Lily family, including daffodils.

- Daffodils include many species and varieties, native to the Eastern Mediterranean, but very hardy, growing very well across North America. It is not uncommon for daffodils to get snowed on and still bounce back! It has even naturalized in many areas, meaning it can survive without a gardener’s help outside of gardens.

- In Germany the wild narcissus, N. pseudonarcissus, is known as the Osterglocke or “Easter bell.” In the United Kingdom the daffodil is sometimes referred to as the Lenten lily.

About Tulips

- Tulips have a very long human history of cultivation, dating back more than a thousand years.

- Tulips were once so popular in the Netherlands that they were used as money in the 1600s!

- Seeds take 7-12 years before they’ll form a flowering bulb

- In Amsterdam, you can go on tours of whole fields and greenhouses of Tulips.

- Tulips are native to N. China / S. Europe, cultivated in Turkey by the Ottoman Empire, imported to Holland in the 1500s.

More from our Botanists

What exactly is a botanist? What types of plants do you study?

A botanist is someone who is curious about plants. That’s it! No degree required, you don’t need to be a professional botanist, but you certainly can be! Like many botanists, I am interested in many different types of plants, but in particular, study plants in our forests, especially our native spring wildflowers.

Why is this information important? Does it connect to other sciences?

The understory layer in our forests comprise many different types of species. In fact, there are far more species in the understory than the overstory! Beyond their beauty, they serve important roles in the how our ecosystem functions – from the flow of nutrients and regulating our climate to feeding bugs, birds, and animals that depend upon them. In particular, I study the impacts of climate change and introduced species in our forests. I use field experiments, observations, and our museum collections to understand the past, present, and future of the plant which we all depend. Botany connects to many areas of science, including agriculture (the food we eat!), medicine, environmental chemistry, and many more. The Section of Botany has even been consulted in legal cases and crime scene investigations.

How long have you been a botanist?

Dr. Heberling: I’ve been fascinated by plants since college, but I actually didn’t refer to myself as a “botanist” until later. Even earlier, I loved nature as a kid and grew up with a garden. Yet, I did not really discover plants as a career or calling until college. I thought I had to be a doctor to go into biology, or at least had to study animals. But at some unknown point, it clicked – plants are incredible and incredibly important! My path to becoming a museum curator was driven by my interests and only partially planned. There are many avenues to explore, many equally as fulfilling and important. And I’m fortunate to have landed where I have, in a collection of more than half a million specimens, studying the power of plants.

What is your favorite flowering plant?

Dr. Heberling: My favorite spring flowering plant: There are many! But I have a special liking to our native Trillium species. Seeing a forest full of Trillium is an experience like no other.

Sarah Williams: Hyacinth because the smell is wonderful. Forsythia because it’s the first sign for me that it’s really real Spring is here. Dutchman’s breeches because they’re pretty and look like tiny teeth.

If a child is interested in plants, what career paths could they follow and where is a good place for children to start that path?

Dr. Heberling: Get outside! That’s the best place to start. It need not be somewhere exotic. Observe. Notice what you notice. Then, start trying to identify what’s around you. Join scouting if you can, or similar groups. The best thing is to discover your passion. There are many careers that involve plants – they not only are part of the landscape, but they ARE the landscape. From agriculture to parks/recreation to many areas of conservation and scientific study – many careers directly involve plants.

Super Science Coloring Pages!

Have fun coloring images featuring animals from our living collection this week drawn by Gallery Presenter and Floor Captain, Jess Sperdute. You can meet some of the animals in the living collection during our Virtual Live Animal Encounters!

The Hunt Is On! Eggs-traordinary Animals That Hide Their Eggs

by Shelby Wyzykowski

Just once every year, an eggs-tra special day rolls around when a certain long-eared, fluffy-tailed fellow comes hopping down the bunny trail to your home. He brings with him all of the egg-ceptionally tasty springtime goodies that he knows will satisfy your sweet tooth. Your basket gets filled to the brim with chocolate rabbits, pastel-colored confections, and chick-shaped marshmallows, just to name a few delectable treats. It’s a holiday candy lover’s dream! But then you may just notice one thing that’s missing…where are all the eggs? No, the Easter Bunny didn’t forget them. He’s giving you a bit of a challenge this year. He’s remembered an old German tradition that started hundreds of years ago. It was so long ago that he had a different name…Osterhase! Osterhase would secretly lay eggs in the back garden so children could enjoy the outdoors and hunt for their Easter eggs. So, like long ago, you get to look outside (virtually) for eggs too! But as you search and discover egg after egg, little do you know that, beyond your garden, there are many more eggs concealed in secret spots. In fact, they’re all over the world…in mountain forests, on ocean shores, and in steamy swamps. But they’re not hidden by the Easter Bunny. All sorts of animals hide their eggs too! Let’s take some time to eggs-plore the planet and learn more about these eggs-traordinary creatures. Let’s go on an egg hunt!

First let’s search out West for the eggs of a plump, short-tailed bird called the American Dipper. They love to live in and around pristine mountain streams ranging from way up in Alaska and all the way down into Panama! That’s a lot of places for them to hide their eggs, so, for now, let’s just focus on one of the Dipper’s favorite spots in Montana’s Rocky Mountains. Dippers are the only songbirds in the United States that love to routinely swim. And they have several adaptations that make dunking and diving quite easy for them. At the base of their tails, they have what is called a uropygial (oil) gland. They use their beak to collect oil from this gland and, when they preen, it makes their feathers waterproof. They also have nictitating membranes (extra eyelids) and flaps of skin covering their nostrils that protect their eyes and beak when they’re submerged.

But all these swim-friendly features can also help immensely when Dippers nest. To keep their eggs safe from predators, they sometimes build their nests in hard-to-reach spots like cliff ledges, on boulders, and under bridges. But there is one very special, watery way that Dippers like to raise their chicks…behind waterfalls! It can get wet if you live behind a waterfall, so a Dipper nest is specially designed to withstand such damp conditions. The dome-shaped nest is about the size of a soccer ball and has multiple layers of moss, bark, leaves, and coarse grass. The thick, outside shell of moss absorbs moisture so the inside, lined with grass, stays cozy and dry. After around two weeks of incubation, the clutch of four to five eggs hatch. Mom spends a lot of time on the nest, but both parents feed the sparsely-downed chicks up to twenty times an hour! They must fly back and forth through the veil of falling water to get to and from their hungry babies.

After a little over three weeks, the fledgling Dippers are old enough to leave the nest. So, they must bravely make their first trip through the curtain of cascading water. Then they watch and learn from their parents how to wade, swim, and dive in the stream to hunt for food. Sadly, the Dipper’s preferred meals (crayfish, tadpoles, fish eggs, and aquatic insects) become scarce when streams are tainted by humans. Poor practices in logging, mining, and farming can cause these birds to abandon polluted areas. Luckily, for now, they do manage to find new locations with clean, cold, rushing water that they can happily call home.

Now let’s travel a few states over to Florida, one of several Southern states where the American Alligator glides through the waters of slow-moving rivers, lakes, and sweltering marshes. In June and July, the female alligator creates a huge nest out of mud, plants, and sticks. It can be up to two to three feet high and as wide as seven to ten feet! The nest needs to be this big because the mother alligator lays as many as thirty-five to ninety eggs. Once the nest is filled with eggs, she completely covers them up with more vegetation. As the eggs rest hidden and undisturbed for several weeks, an interesting process occurs within the massive mound.

Alligator embryos do not have chromosomes that determine gender, so the temperature of the nest determines how many of the young are girls and how many are boys. If, for example, the nest is located on a sunny riverbank (somewhere around 91 to 93 degrees Fahrenheit), the offspring are mostly male. The temperature of a nest in a cool, shady spot might hover around 86 degrees, and that environment produces mostly females. Around the end of August, the baby gators, still safe in their eggs, start making high-pitched noises. This lets their mom know that they’re ready to break out. She uncovers the nest for them to hatch. When the hatchlings are tiny, they hang out in a small group called a “pod”, but mom is always close by keeping a watchful eye on them. Unfortunately, climate change is beginning to affect the behavior of temperature-dependent species like the alligator. They are beginning to nest earlier and earlier in the year to preserve the correct male to female ratio. The alligators instinctively know that they need to keep a gender balance to allow their species to successfully thrive!

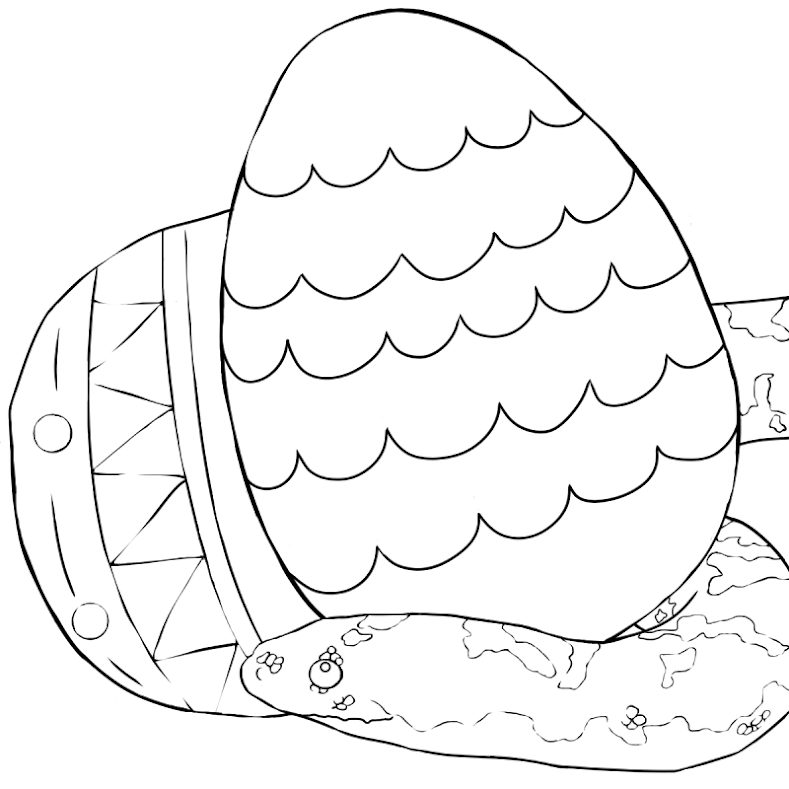

Our last stop covers a wide area, so get ready for the toughest challenge of our hunt! We’re going to search for the eggs of the Loggerhead Turtle. They like to swim in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and the Mediterranean Sea. But between late April and early September, the females leave their aquatic homes to nest on the beaches where they themselves hatched decades earlier. Safely under the cover of darkness, a female Loggerhead will use her powerful rear flippers to dig a hole in the sand. After she lays around one hundred eggs, she once again uses her flippers to expertly cover up her eggs. She does such a thorough job that she erases any sign of her nest…it’s a safe and cozy hiding place for her eggs! They need to be well-hidden because the mother Loggerhead does not watch over her nest. Instead, she returns to the sea, leaving the concealed eggs to develop on their own.

Like alligators, the gender of sea turtle embryos is temperature dependent. A nest in warmer sand produces more females (this biological fact concerns marine scientists because global warming will disrupt the proper male to female ratio). After about two months of incubation, the baby turtles hatch and wait for nightfall. Then in a joint effort, they all climb out of the nest together and make a mad dash for the ocean waves. But their journey is fraught with danger.

Predators such as birds, crabs, dogs, and even raccoons are anxiously waiting to make these little turtles into scrumptious evening snacks. And the hatchlings have another, more insidious hazard to deal with…artificial light. To reach the ocean, the hatchlings use the natural light (the moon and stars) horizon to guide them. But beachfront lighting, highway lights, and campfires can disorient them and lead them in the wrong direction. It’s true that the odds are stacked against them, and even though it’s a treacherous trek to the water’s edge, many do make it. And then the real adventure begins for these little ones in their new ocean home!

Now that we’ve finished our egg hunting eggs-pedition, and you’ve fervently feasted on your Easter treats, your once-filled basket contains only some crumpled foil, a clump of Easter grass, and one squashed jelly bean. And, unfortunately, the only thing that you’ve got plenty of are the pangs of an eggs-cruciating stomachache. But while you’re laying back in your favorite comfy chair recovering from the day’s egg-citement, think about all those creatures out there in the world that work so hard to hide their eggs in the most interesting of places. And that leads you to wondering that maybe, just maybe, there might be one more egg still hidden in your garden. It might be hiding behind the daffodils or under the old wheelbarrow or in the tulip bed. And when you feel better, and you go back outside and find that last egg, it seems to me that would be an egg-cellent way to end an eggs-tra special day.

Shelby Wyzykowski is a Gallery Experience Presenter in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wyzykowski, ShelbyPublication date: March 29, 2021