Leaves have fallen and so has snow, low clouds shroud the blue sky in a drop-ceiling effect, and the frigid air either sits still or stings in gusty winds. Winter can be a bleak and unforgiving season, yet some birds stick around the Pittsburgh area for the coldest months while others arrive here from more northern climates to spend the winter. Why not head to the warmer south like other birds? What food is there among the leafless trees? Who are these hardy little things with wings?

In the forest, the birds work throughout the day. Moving in mixed flocks high up in skeletal trees, chickadees and titmice often lead a band of woodpeckers and nuthatches. The flock probes crevices in tree bark or lingering brown leaves on trees for overwintering insects as eggs, pupae, larvae, or adults. Spiders are also important food items. These invertebrate morsels are fat and protein-rich foods especially important for tiny birds to survive cold nights.

The curious and taunting titmice and chickadees are agile fliers and keep watch for hunting hawks and owls, sending out warning calls to alert the foraging party of danger. On the ground in protected thickets, a different flock searches for food in the forest’s leafy floor. Resident song sparrows and tree sparrows are joined by white-throated sparrows and dark-eyed juncos from the boreal forests. These birds avoid a long migration and the enormous energy toll it takes, choosing instead to scavenge for seeds and insects during the short winter days. Their reward is first dibs on prime summer breeding territory—surely a distant memory to keep them warm during the long, cold winter nights.

When Carolina wrens join these flocks, their trilling and warning calls are distinct. For the naturalist, imitating the warning call of a bird like the wren can lure in a mixed winter flock for easier observation. Relying on a type of voice distortion to lure birds is called “pishing.” It is a great skill for birders to master, and it’s useful year-round. Pishing varies for the bird you want to attract, but usually has a short, staccato “p” straight into a loud “shhh” with variable inflections. The idea of pishing is to attract birds with a warning call, a sort of call-to-arms which then triggers the formation of a tiny bird gang ready to chase off a predator. The birds will often join in with their own warning calls and flit about nervously on nearby branches. Observing the diversity of mixed flocks in the winter demonstrates the unique way these amazing animals work together to survive.

Fall and winter are also the seasons for bird feeders, where hungry foragers can reliably find a banquet of millet, sunflower, and thistle seeds—even better when caked in suet. Under some conditions feeding stations become colorful places. The dull reddish-purple feathers of house finches and purple finches glow against a backdrop of snow, while goldfinches and cardinals ornament nearby trees. Sparrows, titmice, wrens, and blue jays dip in and out at a feeder to fill up on seeds. Chickadees come and peck at empty feeders, calling in a squeaky chant for a refill.

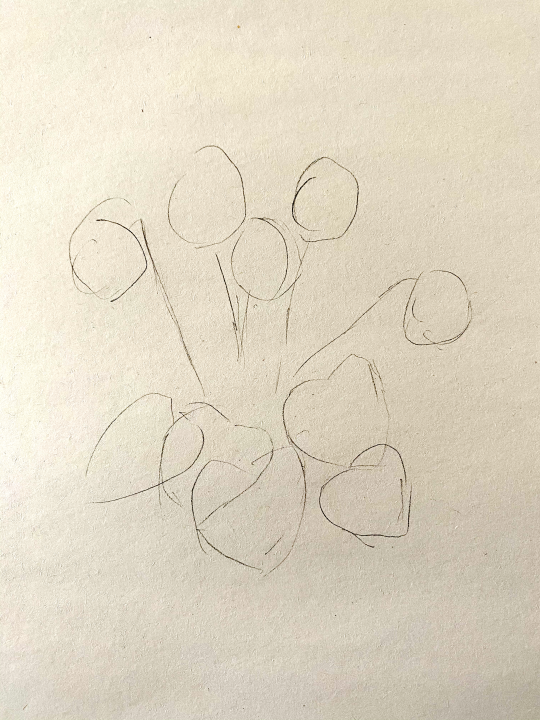

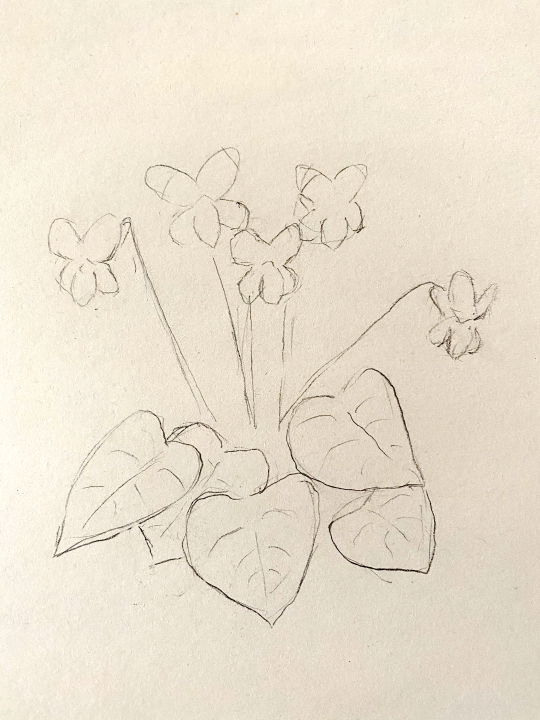

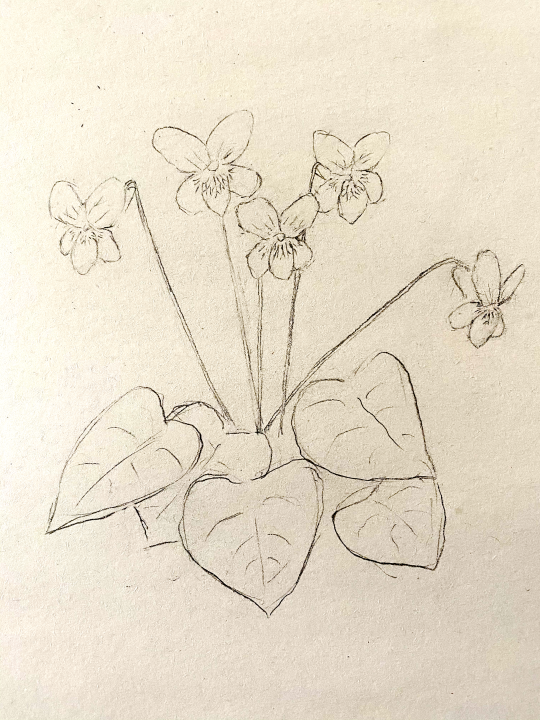

Aaron Young is a museum educator on Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Outreach team. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum. Images from Powdermill Nature Reserve’s bird banding highlights.

Related Content

Bird Safe Glass Installed at Carnegie Museums in Oakland