By Amy Henrici, Collection Manager of Vertebrate Paleontology

You may have noticed that Bears Ears National Monument, southeastern Utah, has been in the National news lately. This vast area of spectacular red rock canyons with Native American ruins was designated in 2016 but is proposed to be reduced by 85%. What hasn’t received much media attention are the Late Paleozoic (~315-280 million years ago) vertebrate fossils collected from this region.

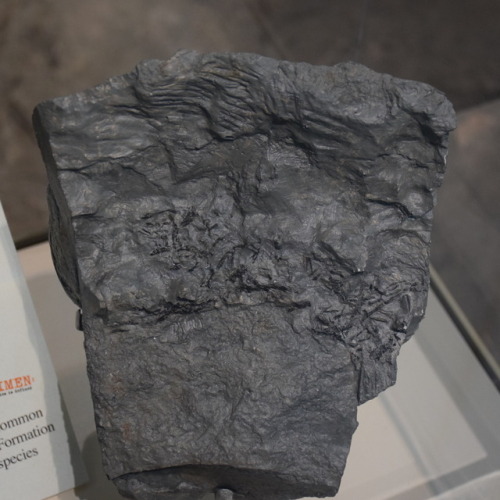

Fossils from Bears Ears N.M. include a variety of freshwater sharks and fishes and amphibians and reptiles, creatures which once inhabited a coastal plain adjacent to an inland seaway. Through the Late Paleozoic the seaway filled with sediment shed from the Ancestral Rocky Mountains to the northeast, and, as the climate became more arid, dunes encroached the coastal plain. The fauna of this changing environment records a primitive stage of the terrestrial ecosystem in which carnivores greatly outnumber herbivores, a stark contrast to modern ratios in which herbivores greatly outnumber carnivores. The most common animals represented in this fossil record are the heavy-bodied, semi-aquatic, carnivore Eryops and the semi-aquatic carnivorous mammal-like reptile, Ophiacodon.

The Section of Vertebrate Paleontology has the best collection of vertebrate fossils from Bears Ears National Monument. Curator Emeritus Dave Berman collected fossils here as a student of Peter Vaughn at the University of California (UCLA). The UCLA Late Paleozoic collection was donated to CMNH in 1988. Berman renewed collecting in the Bears Ears region in 1990, resulting in the discovery of a significant bone bed. CMNH crews in collaboration with researchers from the Illinois State Geologic Survey, University of California at San Bernardino, University of Chicago, and University of Southern California have worked this site since, and a potential new bone bed was discovered last summer.

Funding for field work has been provided by the Bureau of Land Management, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the National Geographic Society.