by Pat McShea

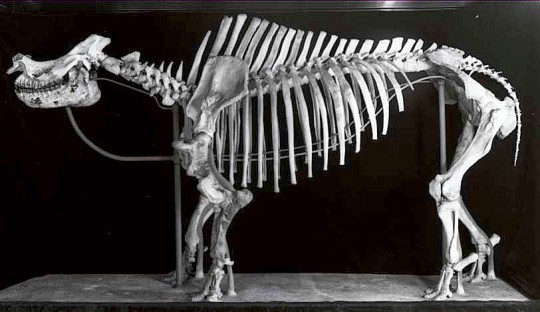

Museum visitors who approach the broad window of PaleoLab encounter an array of large fossilized bones. If not for the pair of microscope workstations positioned against the lab’s right wall, it would be easy to misinterpret the enormous jaws, ribs, vertebrae, and limb bones as evidence of a size bias in the science of vertebrate paleontology.

Small fossils have certainly made mighty contributions to our understanding of life during ancient time periods. Such fossils, which include loose teeth, small bones, and bone fragments, are the primary focus of some paleontological research. In other projects, where considerably larger fossilized creatures are the focus of study, the fossils of smaller creatures add information about species diversity, food webs, and even the climate conditions of ancient ecosystems. The sorting of fossil-bearing matrix that occurs under PaleoLab’s microscopes ensures that important discoveries will continue to occur.

The term matrix refers to the natural rock surrounding a fossil. In the case of fossil bones encased in rock, the matrix consists of the loose sediments that originally buried the bones, sediments that were later transformed into rock over long stretches of time by the pressure of other sediment layers deposited above them. When fossil-bearing rock layers erode, however, and loosened fossils are transported by water, wind, or other forces, the unconsolidated mix of surrounding materials in which the fossils eventually settle is also termed matrix.

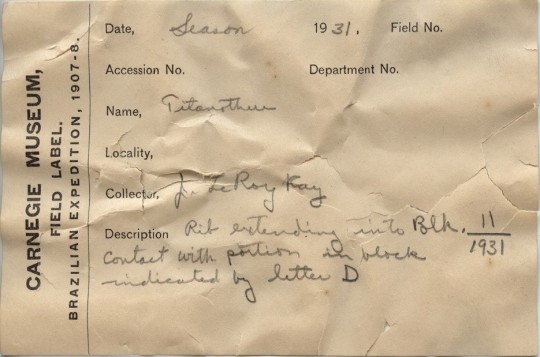

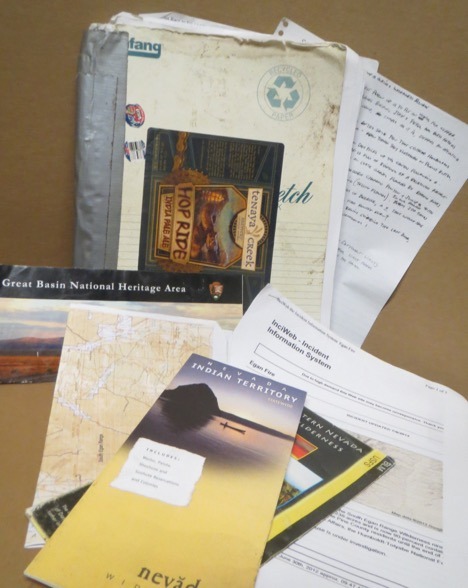

In the field, paleontologists sometimes collect and screen loose matrix on site, using water to both separate floatable bits of plant debris and wash away soil, then sun-drying the resulting sludge for later screening. In the case of the matrix currently being sorted in PaleoLab, material eroded from a more than 50 million-year-old rock unit near Meridian, Mississippi was collected in bulk by CMNH paleontologists and brought back to Pittsburgh for washing and drying at the museum.

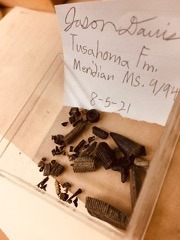

During a recent visit to PaleoLab, Scientific Preparator Dan Pickering pulled two containers from a shelf as “before” and “after” sorting examples. In the “before” container, a quart-sized plastic jug that once held ground coffee, a black, dime-sized shark tooth resting atop similar-sized irregular gray rock fragments hinted at the possible rewards for future sorting efforts. The considerably smaller and lighter “after” container bore not just an array of small marine fossils, including shark teeth and skate tooth plate fragments, but also the name and working notes of the sorter, CMNH volunteer Jason Davis.

Dan termed the recent finds typical for the current operation, but he also noted a now decades-old exciting discovery in matrix screened from a different, but adjacent Mississippi rock unit. In a scientific paper published in 1991, then-CMNH paleontologists K. Christopher Beard and Alan R. Tabrum described a tooth and jaw fragment from an early primate. The fossil was the first record of an early Eocene mammal in eastern North America, and because of its association with well-studied marine fossils, the find helped to better calibrate existing separate biochronologies of terrestrial and marine fossils.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part III: Fossil Preparation

Mesozoic Monthly: Nemicolopterus

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: August 27, 2021