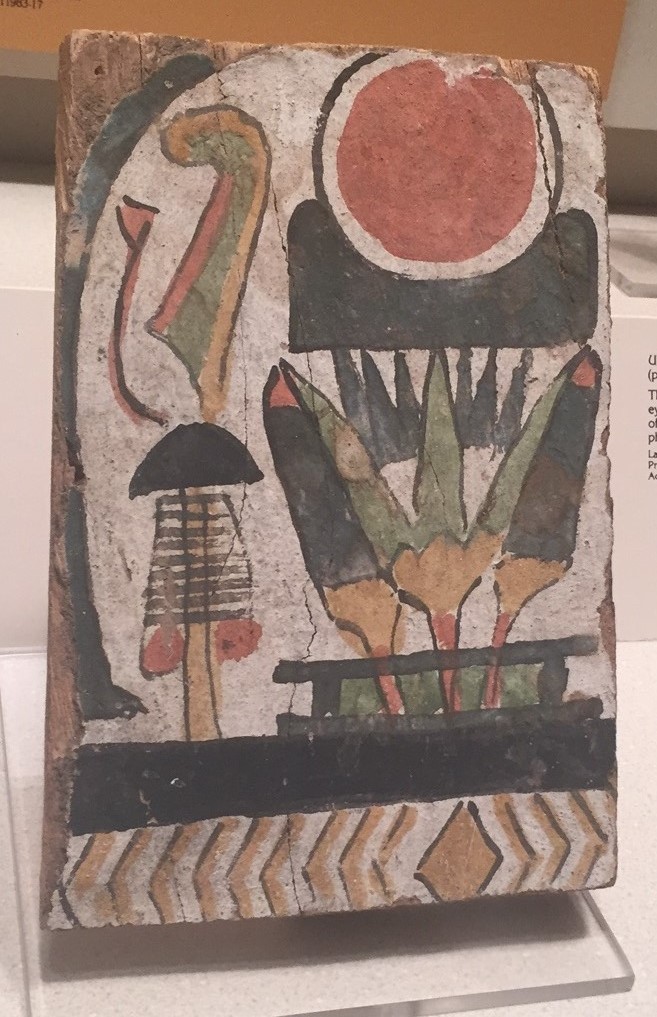

This piece of painted, gessoed wood is on display in Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt. Archaeologists dated it from between 1070 and 653 B.C. and believe it may have come from a coffin. The hieroglyphs on it represent the creator god Re and the afterlife, which symbolically represents creation or rebirth.