by Patrick McShea

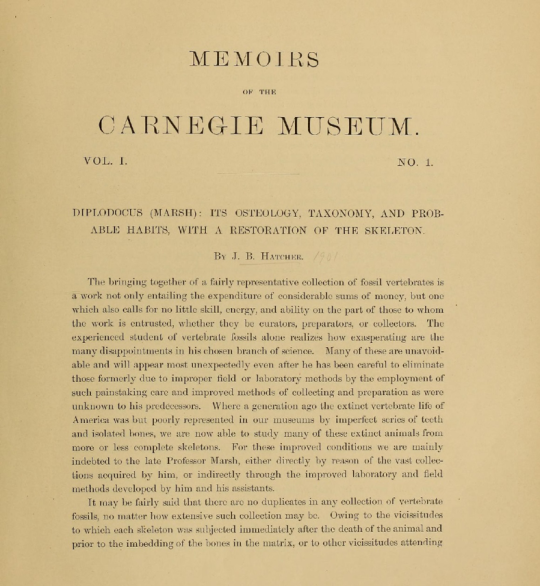

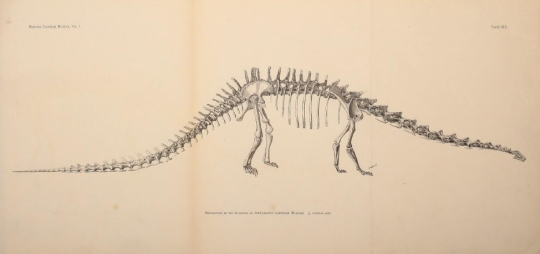

Diplodocus carnegii, a sauropod star of Dinosaurs in Their Time, is not the only large organism exhibited at Carnegie Museum of Natural History that bears the founder’s name. Within the Hall of Botany, the tree-sized saguaro cactus whose prickly form visually anchors the Sonoran Desert diorama is a species know to science as Carnegie gigantea.

The name honors Andrew Carnegie’s support, through the Carnegie Institution, for the 1903 establishment of the Desert Botanical Laboratory in Tucson, Arizona. This groundbreaking research facility, which enabled long-term studies of desert plant adaptations, was sold to the U.S. Forest Service in 1940, and later was purchased by the University of Arizona in 1956.

Today the facility is known simply as the Desert Laboratory, and visitors to its website find an immediate reference to its location on Tumamoc Hill, a site of cultural and spiritual significance to the Tohono O’odham and other Native peoples. A mission statement follows, clarifying the expanded scope of the Laboratory’s work:

The role of the Desert Laboratory is to build on the complementary strengths of culture, science, and community rooted at Tumamoc Hill and the larger Sonoran Desert to become an integrative hub of novel research, education, and outreach about how linked human and natural systems face the future of life in the desert.

Ongoing studies of the Desert Laboratory’s 5,800 saguaros fit perfectly into this mission because of the plant’s importance to the region’s Native peoples for thousands of years.

In Pittsburgh, museum visitors can learn something about the ancient connection between people and the iconic cactus by following a Hall of Botany stop with one in the Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians. Here, near the middle of the exhibition’s central corridor, a series of displays exploring use of plants by Native peoples includes a carving by artist Danny Flores (Tohono O’odham) that depicts the traditional harvest of saguaro fruit by Tohono O’odham women.

Consider the walk between the blooming life-sized saguaro in the Sonoran Desert diorama and the tiny carved replica to represent a spring-into-summer transition when white cactus blossoms, pollinated by bird, bat, or insect, transform into ripening red fruit.

A text panel near the model explains how gathered fruit is boiled to create a syrup which is then fermented into wine used in rituals invoking the summer rains to begin. The label also identifies the source of the specialized harvesting tool, an implement as long as a saguaro is tall. The pole is a saguaro rib, a part of the wood skeleton that once helped to hold a massive cactus upright.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Cactuses, and the Spine of Appalachia

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: March 25, 2021