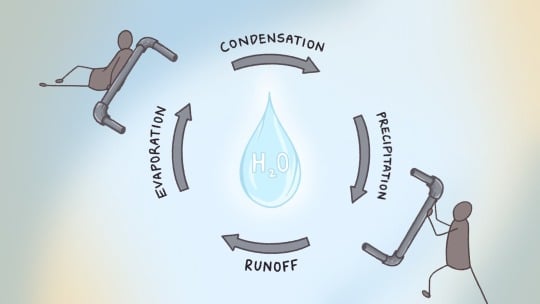

Water is a resource that I often take for granted. I take daily showers, wash my dishes, and do my laundry without a second thought to the amount or quality of water that is used. I only experience small aspects of the natural water cycle on a daily basis, from a bit of condensation on a cold glass of water to the sporadic downfall of rain that occurs in Pittsburgh. The water cycle that I’ve learned about in school can be boiled down to: precipitation, surface runoff, infiltration, evaporation, and condensation; but how do I, as a human being, fit into all of this? What is the human water cycle and how have parts of the water cycle changed within the Anthropocene?

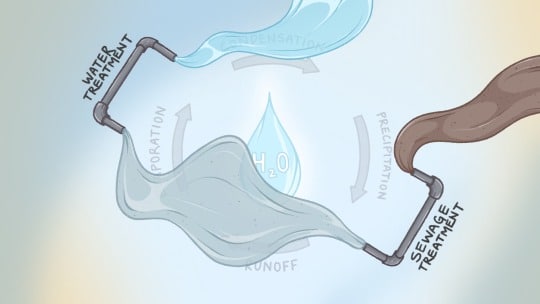

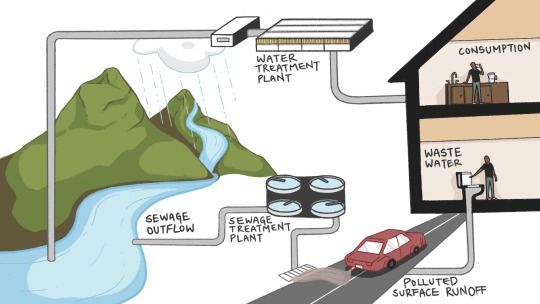

As intrigued as I was, I didn’t know enough about my own impact on the water cycle, so I took a deeper dive into learning about what was actually happening to the water that I used. In order to explore the concept of the human water cycle I needed to start by looking at infrastructure. In the case of water infrastructure, outside of irrigation, the water purification systems and sewage systems are some of the most impactful additions human beings have included into the planet’s water cycle. These infrastructural systems span thousands and thousands of miles underground, connecting houses, neighborhoods, and cities. And yet, at least for me, there was a vast mental disconnect between the water that flows underneath us and the water that we consume. I wasn’t sure how to visualize something that was happening underground, hidden away from sight. That’s when I learned about fatbergs.

In 2017 an 820 foot long mass weighing 130 metric tons was discovered in the sewers of Whitechapel in London, England. The same type of mass, weighing 42 metric tons was found in Melbourne, Australia during the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, most likely due to the flushing of “toilet paper substitutes” (i.e. paper towels, sanitary products, facial tissues). These masses are called fatbergs and can be found in most major cities, especially those with older sewage systems like Pittsburgh. A fatberg is a solidified mass of fat, formed overtime in sewers, that sticks to the build-up of un-flushable sewage. Fatbergs cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to remove, and also reduce river and stream water quality by making sewer overflows more likely. In the Pittsburgh Area, whenever the combined storm and sanitary sewer system is overloaded, excess flow is dumped directly into the rivers.

Fatbergs are a human phenomenon that directly impacts both us and the greater environment. The sewer overflows that they cause impact both the built and natural environment, introducing pollutants such as human waste from our toilets and fats from our kitchen sinks into the living domain. But as harmful as they are, they can be easily prevented.

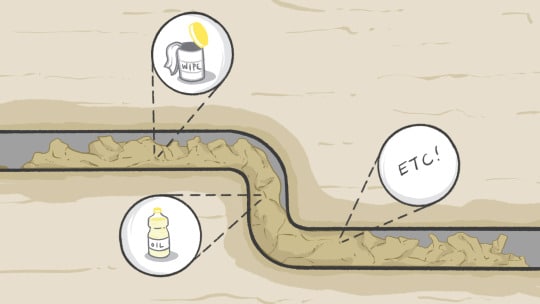

How, you ask? The solution is simple… don’t flush down anything other than toilet paper and bodily waste. But why? What makes toilet paper any different from other paper-like materials? The answer lies in the unique quality of the material that toilet paper is made up of. Unlike paper towels that use long fiber pulps, which improves the strength and absorptivity of the material, and facial tissues that contain additives that hold the fibers together, toilet paper is made using approximately 70% hardwood pulps with short fibers and 30% softwood pulps with longer fibers. Due to the hardwood pulps, once the toilet paper makes contact with water, the short fibers, which also help keep the toilet paper soft to touch, are able to untangle and fall away into smaller fragments, eventually dissolving into tiny bundles of short fiber that can easily flow through the sewage system.

Objects like ‘flushable wipes’, unlike toilet paper, take hours to days to break down. This means that just because we are able to flush something down, doesn’t necessarily make it safe for sewer and septic systems. If you want to try an experiment to explore this concept, try putting ‘flushable’ wipes and toilet paper into two separate containers of water. See for yourself what happens.

Fatbergs are all the more relevant to us during the times of the pandemic, especially in the United States. As people stay home, more objects that aren’t healthy for the sewage system are being flushed. Think about the times you flushed anything other than toilet paper. Are you feeding a potential fatberg in your neighborhood?

Daniel Noh is an intern for the Center for Anthropocene Studies, Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

From the Allegheny to Our Kitchen Sinks