by Nicole Heller

Cities are increasingly important in organizing the experience of people and their interactions with nature. In 1950 there were 2.5 billion people on Earth and 30% lived in cities. Today, there are 7.5 billion people and 55% live in cities. By 2050, there will be an estimated 9.5 billion and 68% will live in cities.

Generally, cities are not good places for other critters to live. The abundance of pavement, buildings, traffic, pollution, pesticides, herbicides, and other hazards make cities really hard places for plants and animals to survive and breed. From a conservation science perspective, cities have long been considered dead spaces, or biological deserts. But more recently researchers are paying more attention to nature in cities. One reason for their interest involves people’s need for nature. Study after study confirms the basic biophilia hypothesis, that people want to associate with nature; they are happier and healthier when they are near plants and animals in their daily lives.

Cities have also drawn the attention of researchers because of some really exciting things are happening within their limits, such as growing populations of peregrine falcons , sightings of rare birds using cities parks during annual migrations, and even discoveries of new species not previously known to science. While cities are overall negative for biodiversity, recent research findings raise important questions: Can human cities be good for non-humans too? Can urban wildlife include a broader spectrum of creatures beyond the common city-adapted species like European sparrows, pigeons, and black rats? What about species special or unique to the regions in which cities are located? How can we make cities work for biodiversity?

A few years ago I posed these questions along with colleagues from the Resilient Landscape program at the San Francisco Estuary Institute. We wanted to learn if there were general lessons that could be distilled from recent and ongoing research projects about what kinds of species can benefit from cities and if so how might city planners utilize this information to prioritize actions that would help cities contribute positively to the resilience of regional biodiversity, or at least do more to diminish the negative impacts.

Earlier this year, some of our findings were published open source in the journal Bioscience, The Biological Deserts Fallacy: Cities in Their Landscapes Contribute More than We Think to Regional Biodiversity, by Erica N Spotswood, Erin E Beller, Robin Grossinger, J Letitia Grenier, Nicole E Heller, Myla F J Aronson.

The study, which includes citations from dozens of regional research projects around the world, identifies five pathways by which cities can help regional biodiversity. “Cities can benefit some species by releasing them from threats in the larger landscape, increasing regional habitat heterogeneity, acting as migratory stopovers, enhancing regional genetic diversity and providing selective forces for species to adapt to future conditions under climate change (e.g., a phenomenon we are calling preadapting species to climate change), and enabling and bolstering public engagement and stewardship.”

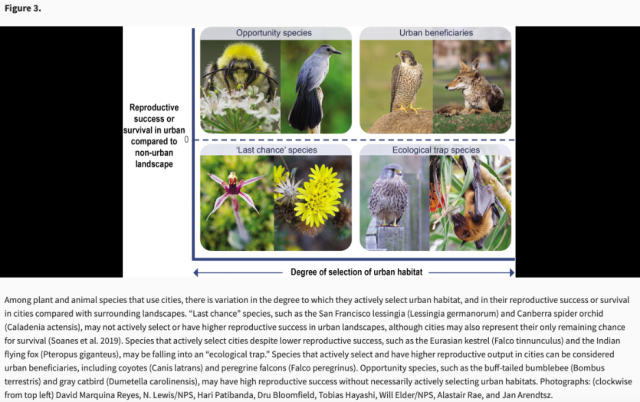

Each of these pathways is described in greater detail in the study. Four categories of species commonly utilize urban habitat, with varying degrees of success, and the study explores examples of how specific species in specific places demonstrate these five pathways.

Overall, the role of cities in supporting landscape-scale biodiversity is an understudied area of research. As cities continue to grow in number and size, human populations rise, and climate change continues, paying attention to the experience of other critters, and how we can make space for them to survive and thrive in anthropogenic habitats, will be more important than ever. This research identifies opportunities to reconcile cities with biodiversity. Opportunities exist to learn more about the unique resources that cities can provide, which specific types of species can take advantage of these resources, and how this information can be incorporated into city plans for parks and green spaces. The San Francisco Estuary Institute has begun this applied work in their report Making Nature’s City, which presents a science-based framework for increasing biodiversity in cities.

What excites me are possibilities if we really try. For the most part cities have been developed with little or no concern for biodiversity. Often people think that humans and nature just can’t coexist. What if city planners and conservation professionals start applying these lessons from ecology more broadly and work together with citizens to deliberately steward biodiversity in cities? How abundant and rich with diverse life could cities become? How happy would that make humans? I wonder. And I am hopeful.

If you are interested in urban nature, you can help to measure its diversity by participating in the museum’s upcoming City Nature Challenge. You never know what you may find in our city. Our combined observations, coupled with the museum’s collections and records, will provide important benchmarks to help track how local species are doing as the region keeps growing and changing in the 21st century.

Full Article Citation

The Biological Deserts Fallacy: Cities in Their Landscapes Contribute More than We Think to Regional Biodiversity By ERICA N. SPOTSWOOD , ERIN E. BELLER, ROBIN GROSSINGER, J. LETITIA GRENIER, NICOLE E. HELLER, AND MYLA F. J. ARONSON BioScience, Volume 71, Issue 2, February 2021, Pages 148–160, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biaa155

Nicole Heller is Curator of Anthropocene Studies at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.

Related Content

Teaching About Local Wildlife with the City Nature Challenge

Air Quality and Urban Gardening

Introducing the Anthropocene Living Room

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Heller, NicolePublication date: April 7, 2021