By Gretchen Anderson, Conservator, and Suzanne B. McLaren, Chair of Collections

What are the risks to a museum’s collection?

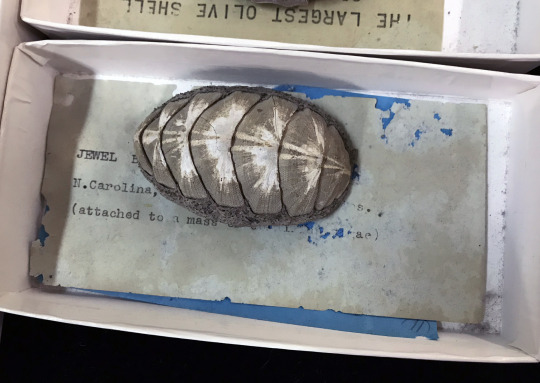

Figure 1: The risks of damage are varied. This photograph illustrates the potential risk of loss of data. The label has been partially eaten by silverfish, damaging not only the paper but ingesting the all-important data about this specific specimen.

The museum is currently engaged in a two-year Risk Assessment process funded by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). We are reviewing a spectrum of potential risks to our collections. This includes everything from fire and water damage to earthquake and pest damage that could affect the Museum’s more than twenty million specimens and objects, both behind the scenes and on exhibit.

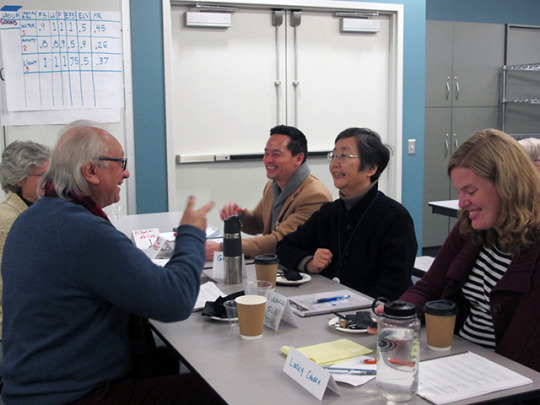

Forty staff members from across the museum attended a weeklong workshop led by our consultant, Rob Waller of Protect Heritage, who has been refining a model of how to quantify risks for more than twenty-five years. This was meant to get us all on the same page when we begin to focus on our individual collections. The workshop offered everyone a chance to see and talk about their individual collections. For most of us, we call this fun. This gave each of us an appreciation for risks to distinct types of collection material. The risk for stone and metal will be quite different than the risk for organic material like birds and plants.

Figure 2: Curators, collection managers, curatorial assistants, educators, exhibits staff, engineers, maintenance and security staff attended the workshop.

Figure 3: The workshop had several days of small group interaction. Here Vertebrate Paleontology Collection Technician Linsly Church, Anthropology Collection Manager Deborah Harding, Collection Associate Marion Burgwin and Minerals Collection Manager Debra Wilson discuss definitions of risk.

We hired Collection Associate Marion Burgwin to work with various staff members on gathering quantitative information on risk from each collection. Collections are divided into twenty-nine units, based on scientific discipline, preservation type and primary use. For example, the Bird collection has four units: study skins & skeletons, nests & eggs, taxidermy, and fluid collections. It is detailed and tedious work – but Marion also gets to see all the cool collections.

Figure 4: Birds Collection Manager Steve Rogers and Collection Associate Marion Burgwin viewing a collection of bird wings. Burgwin is entering the data directly into the Preservation Heritage Data Base.

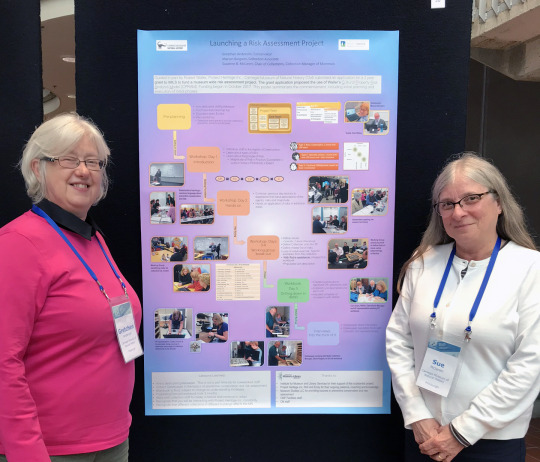

Nearly one year into the project, Conservator Gretchen Anderson and Chair of Collections Suzanne McLaren had the good fortune to present the project and network with colleagues at the annual conference of the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections in New Zealand. Sharing information like this is an important aspect of the support we receive from agencies like IMLS.

Figure 5: McLaren and Anderson with the Risk Assessment poster at the 2018 SPNHC annual conference, Dunedin New Zealand.

Figure 6: A New Zealand native – a highly endangered yellow-eyed penguin.

Gretchen Anderson is a conservator and the head of the Section of Conservation and Suzanne McLaren is the collection manager for the Section of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Have you ever noticed two dark squares in the mural on Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s grand staircase?

Have you ever noticed two dark squares in the mural on Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s grand staircase?