by Debra Wilson

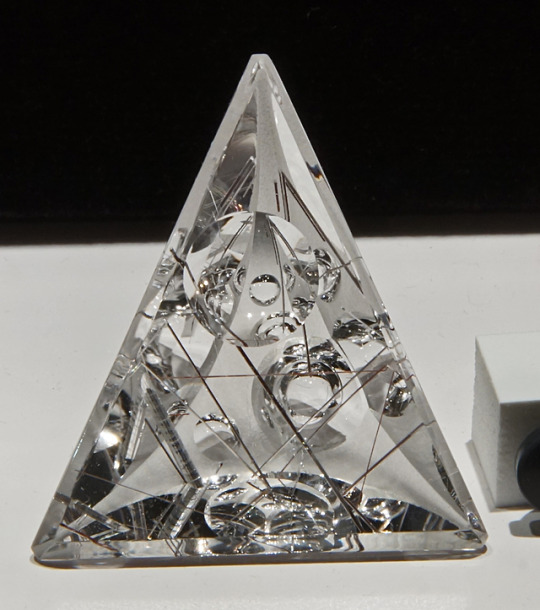

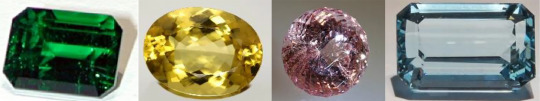

Have you ever gazed up at the sky and noticed a cloud that looks like a face, or an animal, or an object? You can apply the same concept when you visit Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems! Many minerals on display have nicknames because of how they resemble certain animals, objects, or even characters from movies or TV shows. As you walk through the exhibits, let your imagination wander and search for minerals that look like things. Here are some to get you started.

As you enter Hillman Hall, check out the minerals in the Entrance Cube, their nicknames are on the labels. There are many more minerals on display throughout the hall that have acquired nicknames. Here’s just a handful of other nicknames for minerals in the exhibits, see if you can find them. Good luck and enjoy your mineral gazing!

| Nickname | Exhibit |

|---|---|

| The Bat | Igneous Rocks |

| Polar Bear | Weathering Processes |

| Sea Slug | The Maramures District of Romania |

| The Chariots | The Maramures District of Romania |

| Smog Monster | The Maramures District of Romania |

| Sea Serpent | Pennsylvania Minerals and Gems |

| Pine Trees On a Cliff | Oxides |

| BBQ Chips | Masterpiece Gallery |

| Cookies and Cream | Masterpiece Gallery |

Debra Wilson is Collection Manager for the Section of Minerals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

How Do Minerals Get Their Names?

What Does Pittsburgh Have in Common with Mount Vesuvius?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wilson, DebraPublication date: June 28, 2024